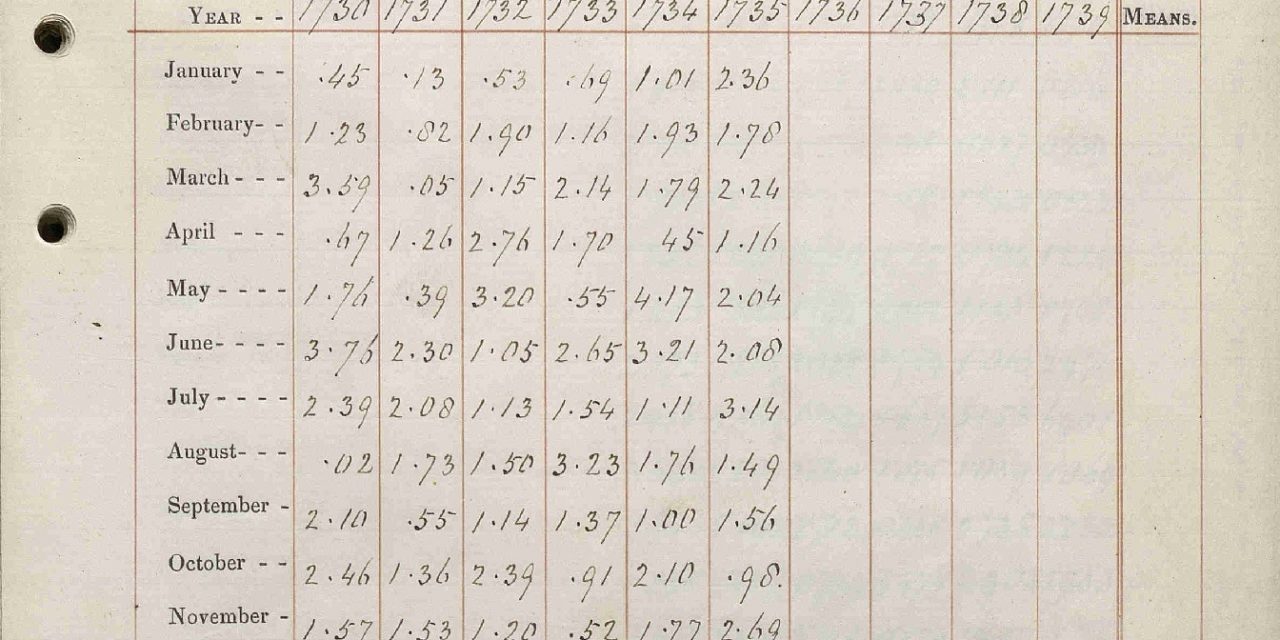

In March 2020, as billions of people found themselves suddenly stuck indoors in the shadow of the then-new coronavirus pandemic, University of Reading (Berkshire, England) climate scientist Ed Hawkins saw a unique opportunity. The U.K. Meteorological Office had just scanned and made publicly available approximately 300 years of archived, handwritten rainfall observations dating as far back as 1677. However, without manual transcription of these approximately 5.2 million datapoints, they were of little use to researchers interested in long-term analysis.

Hawkins recognized that despite covering a significant breadth of time and geography, the written observation sheets each followed a standardized, 10-year format that allowed for easy comparison between them. With only basic instruction, the task of transcribing the massive number of measurements could be completed by just about anyone. And with more people at home and in need of distractions than ever before, the likelihood of finding willing transcribers was high. Hawkins established a project titled Rainfall Rescue on the popular citizen science website Zooniverse on March 26, 2020, asking volunteers to help build a searchable database of U.K. weather observations from 1677 to 1960. By April 10, more than 16,000 volunteers had helped Hawkins transcribe the entire archive.

Two years later, a recent paper by Hawkins about Rainfall Rescue published in the Geoscience Data Journal describes that approximately 3.34 million new observations had successfully passed a rigorous quality control process and become part of the U.K. Meteorological Office’s official record of historical precipitation. The additional data extends the continuous record of precipitation in the U.K., Ireland, and the Channel Islands back 26 years from 1862 to 1836 — and even earlier in some areas.

“I am still blown away by the response this project got from the public,” Hawkins said in an April 2022 statement about the campaign. “Transcribing the records required around 100 million keystrokes, yet what I thought would take several months was completed in a matter of days.”

Ensuring Quality Among Quantity

After Rainfall Rescue, the next task was to arrange, contextualize, and quality check the transcriptions, transforming raw data into chronological records for more than 6,000 locations. Part of this quality assurance process was built into the initial transcription effort, Hawkins described. Each handwritten observation was transcribed by at least four volunteers to ensure accuracy — if at least three volunteers agreed on a measurement, it would be “provisionally accepted.” These provisionally accepted values accounted for around 98% of all data, but even verifying the remaining 2% represented a significant undertaking.

Eight volunteers, listed as study co-authors, continued to work alongside Hawkins to check the accuracy and scientific integrity of the provisionally accepted values as well as reconcile differences among the remainders. This process involved, according to the study, eliminating measurements described by the original recorder as “estimated” or adapted from an unconfirmable source, such as an almanac, and ensuring that the sum of monthly precipitation values equaled recorded annual totals, among other protocols.

The verified data revealed much about locally observed rainfall patterns across the British Isles before national meteorological organizations began systematically measuring precipitation in the 1960s. For one, contemporary data maintained by the U.K. Meteorological Office suggested that May 2020 was the driest May in the country’s history. The new data indicates that May 1844 was even drier, receiving about 1.3 mm less rainfall. The driest full year in U.K. history was previously thought to be 1887; now, it is believed to have been 1855.

“As well as being a fascinating glimpse into the past, the new data allows a longer and more detailed picture of variations in monthly rainfall, which will aid new scientific research two centuries on,” Hawkins said. “It increases our understanding of weather extremes and flood risk across the U.K. and Ireland and helps us better understand the long-term trends towards the dramatic changes we’re seeing today.”

The Original Citizen Scientists

Beyond the data itself, Rainfall Rescue yielded interesting information about the rainfall observers who perhaps served as the region’s first citizen meteorologists. The data — as well as the notes routinely left by the observers who gathered it — detail a broad range of people united by their often decades-long commitment to monitoring and documenting local precipitation.

Private rain gauges were typically located near churches and chapels, schools, reservoirs, parks, railway stations, and lighthouses, in addition to private residences. They were typically monitored and maintained by individual enthusiasts or families rather than scientific groups. Perhaps even more diverse than their settings and operators, however, were the reasons provided for why periodic rainfall measurements at a particular gauge would suddenly stop. In his recent paper, Hawkins lists some of these reasons:

- At a rectory in Kent, an observer in 1863 found their gauge “choked with a bird’s nest.”

- In Eltham, London, at the outset of World War II, an observer recorded that their gauge had been “destroyed by enemy action.”

- In 1951, an observer noted that a gauge on the grounds of a South London mental hospital had been “hidden by inmates,” interrupting recordings for three years.

- Gauge recordings suddenly stopped at a home in West Ayton, Yorkshire, after the observer reported that they were “too old to bother now.”

Read the full, open-access paper, “Millions of historical monthly rainfall observations taken in the UK and Ireland rescued by citizen scientists,” in the Geoscience Data Journal.

Top image courtesy of U.K. Meteorological Office/Rainfall Rescue

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.