During the 19th century, as the number of residents living in U.S. cities boomed and buildable space in urban centers dwindled, alleyways became a staple of municipal planning. These narrow passages kept intracity access intact for pedestrians, horses, and service workers while also mitigating street congestion as traffic increased. Today, however, many alleyways carry unfortunate reputations as dirty, dark, and unsafe. In addition to their social ills, alleyways typically feature impervious surfaces that burden nearby storm sewers by generating runoff.

A growing number of U.S. cities are leveraging green infrastructure to transform dilapidated alleyways into attractive and functional community spaces. Among them is Los Angeles.

A joint initiative by the city, the Trust for Public Land (TPL; San Francisco), and other partners is finalizing the third phase of a long-term campaign to distribute green alleys across the city’s most socially vulnerable and flood-prone areas. These green alleys focus on safety and accessibility in addition to stormwater management. They add lighting and signage as well as permeable pavers, bioswales, and dry wells, described TPL Los Angeles Parks for People Program Manager Pamela Soto.

“These urban alleys are multiple-benefit projects that incorporate urban greening, create safer passages for walking and biking, and connect important community assets,” Soto said. “There are 900 linear miles [1,450 linear km] of alleys in Los Angeles that are typically ignored, and we’re working to make these spaces into vibrant, outdoor areas for pedestrian travel with improvements.”

Rethinking Los Angeles’ Alleyways

Residents of South Los Angeles have few local options when it comes to green spaces. In 2015, the region contained less than 0.2 ha (0.5 ac) of park space per 1,000 residents — about 93% lower than the average ratio of parks to people throughout the rest of Los Angeles, according to TPL estimates. At the same time, South Los Angeles contains as much as 30% of the city’s alleyways. Sensing an opportunity, TPL collaborated with the City of Los Angeles’ Community Redevelopment Agency, Los Angeles Sanitation and Environment, the University of Southern California (Los Angeles) Center for Sustainable Cities, and others to develop the South Los Angeles Green Alley Master Plan in 2015, Soto said.

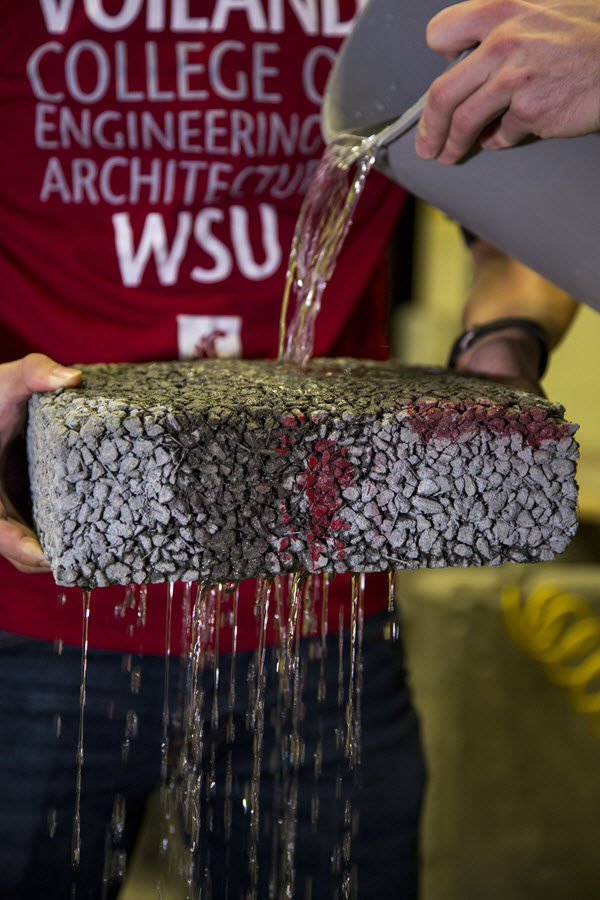

For their first green alley demonstration project, the partnership looked to Los Angeles’ South Park neighborhood. Focusing on six city blocks surrounding an existing park, the team sought to redesign six alley segments that would work together to create safe and convenient pedestrian access between the park and local homes, schools, and businesses. Project partners redesigned alleyways covering a total of 0.7 ha (1.8 ac), adding permeable interlocking pavers supplemented by underground infiltration trenches and dry-well systems. The revitalized alleys also feature educational signage, artwork, lighting fixtures, as well as extensive native vegetation, including nearly 150 new street trees. Since its completion in October 2016, the South Park green alley network has captured, treated, and infiltrated more than 7.5 million L (2 million gal) of stormwater per year from its surroundings. The alleys discourage flooding and keep pollutants out of the nearby Los Angeles River.

Shifting their focus further north, the partnership completed its second green alley project in the Pacoima neighborhood in October 2020. The Bradley Green Alley project was designed to redirect runoff to help replenish the San Fernando Valley Groundwater Basin. The plan redesigned a 244-m (800-ft) -long, 8-m (25-ft) -wide artery with similar green infrastructure elements to the South Park project as well as new bioswales on either side of the alley. It also added new seating, play areas, fitness facilities, picnic tables, and public art.

Today, the Bradley Green Alley infiltrates approximately 7.5 million L (2 million gal) of stormwater per year into local aquifers while providing new community amenities, according to Los Angeles Sanitation and Environment.

Now project partners are finalizing two additional projects in South Los Angeles: the Central-Jefferson High and Quincy Jones green alley networks. Reconstruction of the 11 alleyways included in the projects are already largely complete, with a ribbon-cutting scheduled for March, Soto said. Like the other green alleys, the Central-Jefferson and Quincy Jones networks will feature permeable pavers, infiltration trenches, bioswales, and dry wells, in addition to community amenities and other green infrastructure elements. Preliminary monitoring by TPL shows that the new alley networks already are proving their worth, mitigating flooding during an especially rainy wet season in late 2022.

“For our Central-Jefferson and Quincy Jones projects, we have recorded data on how much stormwater each has been able to capture,” Soto said. “For Central-Jefferson, it has captured 1,300,000 gallons per year and for Quincy Jones, 263,000 gallons per year.”

Alley Transformations Meet Multiple Goals

Los Angeles follows the example of several other U.S. cities that regard alleyways as opportunities to improve social and environmental well-being.

Chicago is perhaps the earliest adopter of the green alley concept among large U.S. cities. The Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) built the city’s first green alleys in 2001. This experiment matured into an organized program resulting in the redesign of more than 300 alleys citywide.

In 2010, CDOT released The Chicago Green Alley Handbook, that summarizes lessons from the city’s green alleys campaign and provides a roadmap for other cities interested in the concept. The guide provides an in-depth investigation of the technical aspects underlying green alleys as well as ways to tailor their design according to community needs. Through various Chicago case studies, it details how cities can construct green alleys across a range of different sites and contexts. The handbook also touches on financing, operations, and maintenance concerns.

In Austin, Texas, a partnership between the University of Texas at Austin, nonprofit Community Powered Workshop (Austin), and the Guadalupe Neighborhood Development Corporation underway since 2005 is pioneering the alley flats concept. These small, detached residential units focus on sustainable design. They incorporate permeable pavers, native vegetation, and other green infrastructure elements and provide new, affordable housing units in areas where homelessness is high.

Meanwhile, the Alley Network Project underway in Seattle works to make better use of the city’s alleys by turning them into safe and attractive event spaces. In Seattle’s historic Pioneer Square, the Alley Network Project has designated two large alleys — Nord Alley and Pioneer Passage — as festival streets. This allows for their temporary closure to traffic for events. The surfaces of both alleys were reconstructed using permeable, clay-based pavers, enabling them to infiltrate stormwater while still accommodating limited vehicle traffic. Since their redesign, the alleyways have hosted such events as art shows, poetry readings, pet adoption events, and viewing parties.

Top image courtesy of layacarlos16/Pixabay

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.