The City of Jacksonville, Florida, is embracing a combination of artificial intelligence (AI), geographic information systems (GIS), and aerial imagery to create a high-resolution map of more than 350,000 parcels in Duval County.

The map, to be developed by Ecopia AI (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), aims to help the Jacksonville Department of Public Works more accurately assess pervious and impervious space on private properties. This data will enable the city to easily determine landowner obligations under its impervious area charge (IAC) program, as well as seamlessly update those charges in response to changes made by landowners. The new mapping initiative responds to the results of a 2019 audit of the IAC assessment process, which determined that the previous, manual approach to quantifying fees resulted in sluggish and inconsistent application.

“With this data informing our stormwater mapping workflows, the City of Jacksonville will ensure stormwater utility fee billing is as accurate and efficiently calculated as possible for 2023 and beyond,” Steve Long, Director of Public Works for the City of Jacksonville, said in a release.

Jacksonville in 24 Trillion Pixels

Jacksonville is among thousands of communities that assess IACs to property owners. While these fees are often a key funding source for local stormwater management activities, the size and complexity of the data required to apply them accurately presents a logistical challenge. In recent years, a growing availability of satellite, aerial, drone-enabled, and street-view images as well as technological advances in AI and GIS systems have made developing large-scale, digital maps an increasingly viable solution to this challenge for municipal stormwater managers, said Ecopia Senior Director of Public Sector and International Development Brandon Palin.

“In the last decade, we’ve seen the geospatial and AI landscapes both evolve drastically,” Palin said. “More and more organizations are leveraging the power of geospatial data and mapping as the availability of GIS tools has expanded.”

The map development process begins by sourcing an array of images representing the region. Ecopia relies on a network of partners to collect these images. Partners include such large geospatial players as Esri (Redlands, California) and European Space Imaging (Munich).

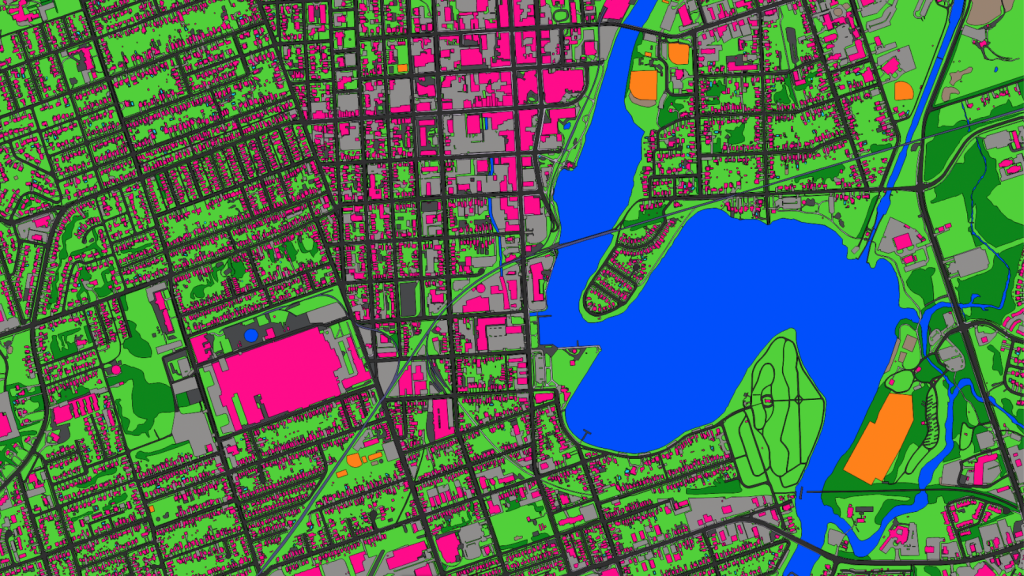

Developers then apply an AI algorithm that considers each image pixel by pixel — in the Jacksonville case, approximately 24 trillion of them in total, Palin said. The algorithm uses examples from other images to determine whether each pixel, which represents just over 7.5 cm2 (1.2 in.2) of real-world space, features pervious or impervious coverage.

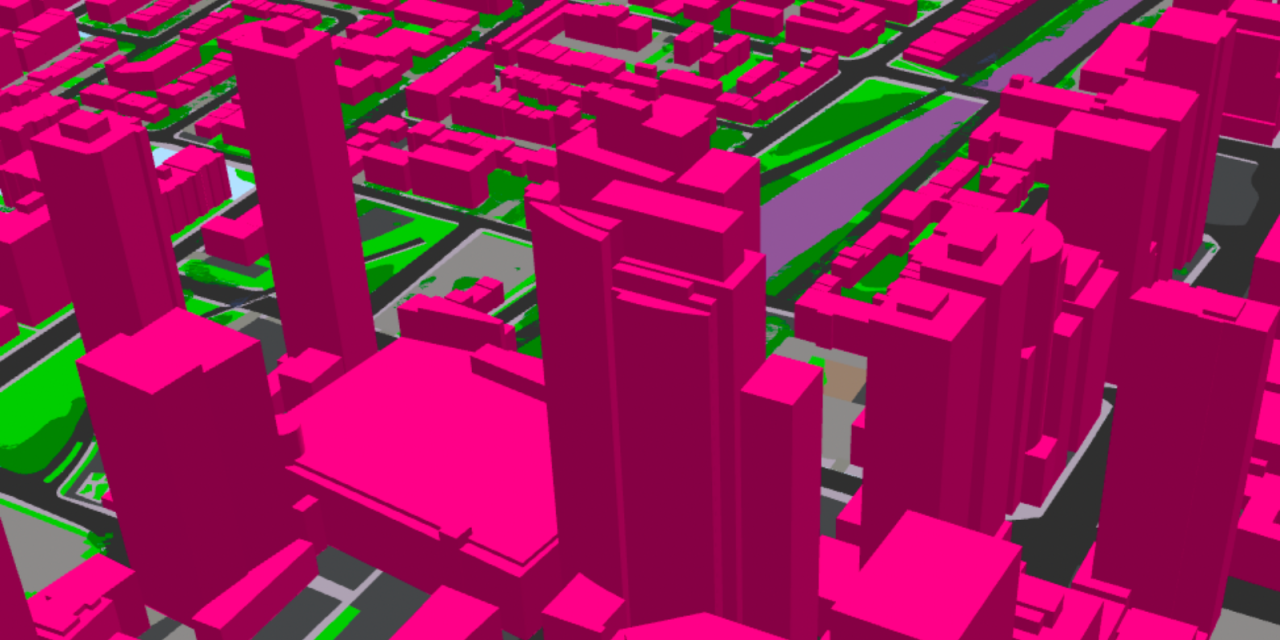

The algorithm can accurately distinguish between more than 20 types of land cover. This includes being able to discriminate between paved and unpaved roads and driveways, as well as between swimming pools and open water. The algorithm uses these results to render both two- and three-dimensional maps, which automatically self-update when fed newly acquired images from ongoing monitoring campaigns.

Although Jacksonville’s map caters narrowly to facilitating the IAC assessment process, Palin described that the same technology also can address other large-scale stormwater management issues. An August 2022 partnership with the Los Angeles Bureau of Street Services, for example, produced a map that now helps stormwater managers identify optimal locations for runoff outlets and vegetation in street medians. An AI-generated map of Peterborough, Ontario, estimates the likelihood that a specific point will experience surface flooding based on different climate-change scenarios.

“Our maps ultimately provide an accurate, comprehensive, and up-to-date digital representation of the real world, and are a source of truth for solving some of the world’s most complex challenges,” Palin said.

The Rise of Digital Twins

This type of high-resolution, real-time, digital representation, intended to accurately mimic current conditions in a physical location, is known as a digital twin.

During a technical session on stormwater technology at WEFTEC 2021, EcoLucid (Boston) CEO Marcus Quigley claimed that imaging technology underpinning digital twins will prove capable of mapping every point on Earth at 5-cm2 (0.8-in.2) resolution by 2025. This prediction is already proving true ahead of schedule, according to Palin.

“The imagery that we use as an input is being produced faster and at higher resolutions,” Palin said. “We envision these capabilities to continue improving and driving innovation in the industry, leading to more advanced features such as indoor mapping, augmented reality, and other layers of information that comprise a true digital twin of the physical world.”

However, just as important as the technology’s sophistication is its accessibility, Palin said. Only a few years ago, applications for digital-twin technology came at a price only affordable by a small handful of cities. A 2019 report from ABI Research (Oyster Bay, New York) predicted that more than 500 cities around the world will actively utilize these types of digital twins to aid in decision making by 2025, and that the costs for developing them will steadily decrease as imaging and modeling technologies advance.

“With the emergence of more efficient processing, we are seeing an increase in data equity across the world,” Palin said. “Decision-making powered by highly accurate geospatial data is now advancing communities that historically would have lacked such information, and we expect this trend to increase with the continuous innovations in AI.”

Top image courtesy of Ecopia AI

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.