Implementing green infrastructure often provides a diverse range of benefits, from keeping stormwater contaminants out of waterways to improving property values. For a group of seven University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture (UTIA; Knoxville) students who designed, constructed, and released floating wetlands in a tributary of the Tennessee River this semester, pursuing green infrastructure came with an additional reward: class credit.

The floating wetlands — elevated, raft-like garden beds that hover on the waterline of Third Creek — are the culmination of months of work by students in UTIA’s Green Infrastructure course. Built at minimal cost from materials gathered around the UTIA campus, the wetlands passively remove nutrients and other pollutants from Third Creek while enhancing biodiversity in a bustling, urban area.

While designing and building the floating wetlands are a key component of the UTIA course, instructor Mike Ross describes another critical lesson he aims to teach is agency. Ross, an assistant professor in UTIA’s Department of Plant Sciences undergraduate program and the University of Tennessee’s (UT) School of Landscape Architecture, emphasized that the course empowers students to improve the health of their local environment without the need for costly materials or professional supervision.

“I approach green infrastructure from the point of view of an activist,” Ross said. “By building these wetlands, our students learn about what they can do to improve the Tennessee River, provide wildlife habitat, and promote environmental justice and equity.”

From Theory to Practice

Students begin the course by learning about green infrastructure fundamentals, which takes them outside the classroom to study an array of real-life examples on campus. Much of the University of Tennessee (UT) campus contains scattered bioswales, cisterns, permeable pavers, and other nature-based stormwater solutions, in addition to the UT Gardens, a large botanical center featuring additional rain gardens and green roofs.

With a better understanding of green infrastructure’s environmental, economic, and social benefits, the students then put theory into practice by addressing an on-campus water quality hazard. Ross describes that many stretches of Third Creek, which winds through the UTIA campus, contain little or no buffer vegetation to remediate pollutants from urban runoff before they reach the waterway. At the same time, eastern Tennessee is experiencing a gradual invasion from non-native bamboo species, which threaten to disrupt and distort the region’s natural ecosystem.

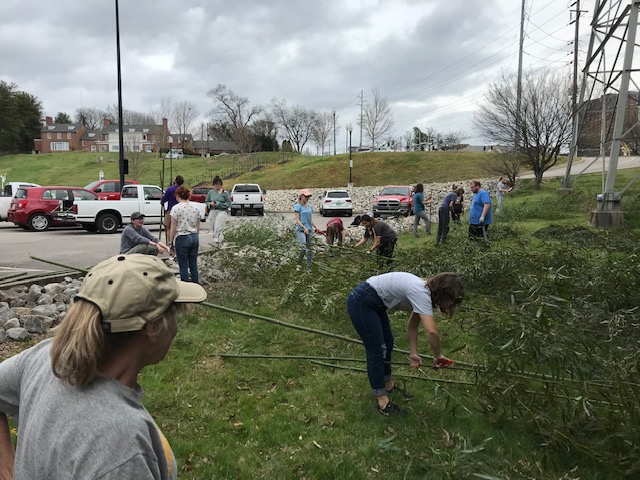

To build an intervention that would address both problems, students first traveled throughout the Tennessee River watershed last spring to cut and gather invasive bamboo. Shaping and binding the shoots into multi-layered, hexagonal figures provided foundations for the floating wetlands that would be sturdy enough to support weight as well as buoyant enough to float. Above the foundations, students layered landscaping mats, soil, and various native plants.

Plant species included in the garden were thoughtfully chosen, Ross described. For example, because thousands of monarch butterflies pass through Knoxville each fall to migrate, the gardens contain milkweed and other butterfly attractants to help sustain them on their journey. UT is also a recognized Bee Campus, so the design includes several pollinator-friendly species.

“We are designing with living, fellow organisms,” Ross said. “Plants are not pretty objects to be placed in a static composition. Landscapes are connected, dynamic, and evolving. Whether plants grow or die, they tell us something, and we must be willing to interpret and base design and management decisions on a respect for nature’s well-being.”

Cumulative Benefits

Floating wetlands have been a hallmark of Ross’ career, in part for their ability to provide various co-benefits at minimal cost. As a graduate student at Texas Tech University (Lubbock), for example, his thesis proposed installing floating wetlands in the Chicago River to remediate industrial pollutants.

A landscape architect by training, Ross described his belief that ecological design should be both visually pleasing and functional, improving both the social and environmental health of its surroundings. When he joined the UTIA teaching staff in 2019, he proposed replacing a course on ornamental landscape design with a course on green infrastructure, which would better equip students for careers in the growing field of low-impact development. University administrators were eager to pursue the new course, Ross said, which better aligned with its sustainability efforts.

With an eye toward next semester, Ross said he envisions that each group of students who take his green infrastructure course will build and deploy new floating wetlands as a capstone project. Over time, the hope is that this ever-growing number of gardens will have a cumulative, lasting effect on the water quality and biodiversity of Third Creek — while also giving tomorrow’s green infrastructure professionals the experience they need to succeed in their careers.

“I have hope that students and citizens alike will use their agency to improve where they live,” Ross said. “This is our drinking water. Do we, one day, want to fish in the Tennessee River? Do we want to wade in Third Creek? These are not insurmountable goals.”

Top image courtesy of Ross/University of Tennessee, Knoxville