Increasing U.S. wetland coverage by 10% could cut nitrate levels in rivers and streams by as much as half in areas with the highest levels of nitrate pollution, according to new research.

The finding comes from a recent study published in the journal Nature, in which researchers from the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Waterloo (Ontario, Canada) attempted to quantify the nutrient-removal effectiveness of current U.S. wetlands as well as recommend ways to make the most of new ones.

Their research finds that the effects of nutrient pollution would be far worse without existing wetlands — and stand to become much more manageable with the construction of new, strategically placed wetlands.

Spend More to Get More

The researchers write that U.S. federal policy toward wetland construction and restoration has largely been non-targeted, such as providing grants to states and towns to build wetlands on a voluntary basis. Extrapolating from existing data about these programs and their effects on nutrient levels, study authors write that increasing U.S. wetland coverage by 10% using the conventional, non-targeted approach would cost up to $2 billion in total and increase nitrogen removal by approximately 22 KT (22 million kg).

But a targeted approach could yield much greater results. While building or enhancing wetlands strategically in areas with the highest historical nitrogen concentrations would increase the cost of a 10% increase in wetland coverage to about $3.3 billion, it could remove about 860 KT (860 million kg) total nitrogen per year — as much as 40 times the benefits of the non-targeted approach, the study describes.

According to the team’s estimates, a 10% increase in wetland coverage using a targeted approach could drive up nutrient removal rates in the U.S. by up to 54% compared to their current values.

“You get much more bang for your buck if wetland preservation and restoration are targeted,” said Nandita Basu, study co-author and University of Waterloo environmental scientist, in the release. “From a policy perspective, it is dramatically more effective and efficient.”

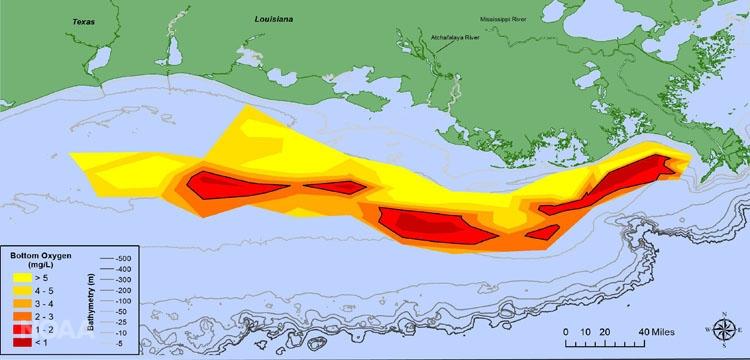

The research team writes that new wetlands could have the most dramatic benefits along the Mississippi River, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies as the largest nutrient contributor to the Gulf of Mexico. Almost every summer, nutrient accumulation in the northern Gulf of Mexico results in the formation of a massive HAB measuring an average of 14,000 km2 (5,400 mi2) — an area incapable of sustaining aquatic life about the size of Lake Ontario.

Estimates from the study suggest that existing wetlands along the Mississippi River currently reduce nitrogen inputs to the Gulf of Mexico by about 50%. Spreading wetland coverage, particularly in the Lower Mississippi River Basin in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi, would further reduce nitrogen loads, the researchers write.

Assessing Nature’s Filter

Wetlands naturally contain heterotrophic bacteria that feed on the nitrates in runoff in the presence of carbon, converting them to harmless nitrogen gas while releasing clean water downstream. Wetland denitrification effectiveness is traditionally difficult to quantify on a national scale because performance rates fluctuate based on site-specific factors such as temperature, biodiversity, and size.

To arrive at their findings, the research team aggregated a broad dataset using information from the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and other authoritative sources to create county-by-county maps of nitrogen transport across the 48 contiguous states between 1930 and 2017. Cross-checking their maps against wetland coverage and health information from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Wetland Inventory, researchers were able to identify points where wetlands result in the greatest nitrogen reduction in runoff before it runs downstream as well as ideal, high-nitrogen locations for new wetlands.

“Unfortunately, most wetlands that originally existed in the U.S. have been drained or destroyed to make way for agriculture or urban development,” according to co-lead author Kimberly Van Meter of the University of Illinois at Chicago in a December 2020 release. “Ironically, areas with the biggest nitrate problems due to agriculture and intensive use of nitrogen fertilizers are also usually areas with the fewest numbers of remaining wetlands.”

Read the team’s study, “Maximizing US nitrate removal through wetland protection and restoration,” in the journal Nature.

Top image courtesy of cocoparisienne/Pixabay