Study claims stormwater infrastructure design standards fail to keep pace with today’s precipitation

Stormwater management regulations have come a long way since U.S. Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972.

Climate change results in more frequent and intense precipitation because warmer clouds can hold – and drop – more water. However, the standards that U.S. stormwater professionals use to design infrastructure hinges on data more than 50 years old. A new study calls for revised design standards for stormwater infrastructure designs that account for the changing definition of an “extreme storm”.

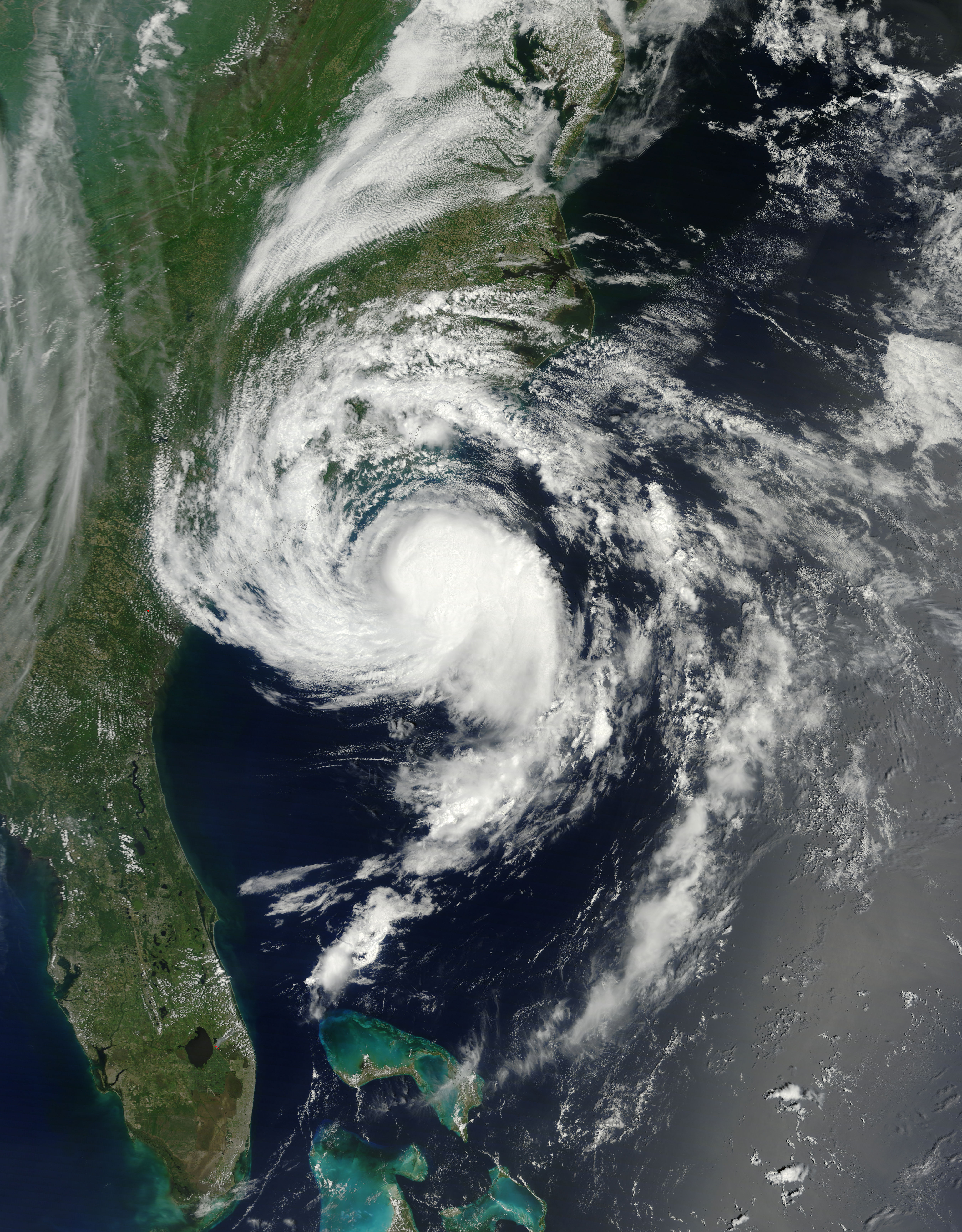

U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Back then, stormwater dischargers were largely exempt from National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit requirements until the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency developed specific regulations for urban stormwater management in 1976. These regulations expanded over the following decades, requiring a wider array of dischargers to responsibly manage stormwater. In more recent years, the concept of green stormwater infrastructure has grown in prominence.

Despite more comprehensive regulations, however, the precipitation data used in the design of much of today’s stormwater management infrastructure may be outdated. Stormwater infrastructure designed to handle what yesterday’s stormwater professionals would consider a “100-year storm” – a storm with a 1% chance of occurring in a given year – will likely fail to manage flooding from today’s severe storms, argues a new study from University of Wisconsin—Madison (UWM) and Carnegie Mellon University (CMU; Pittsburgh) researchers.

“The take-home message is that infrastructure in most parts of the country is no longer performing at the level that it’s supposed to, because of the big changes that we’ve seen in extreme rainfall,” Daniel Wright, a UWM hydrologist and lead author of the study, said in a release.

Relying on yesterday’s data

The researchers write that much of today’s stormwater infrastructure and hydrological studies were planned using intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curves developed by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NOAA develops IDF curves using an array of historical weather data to predict the effects of a severe, 100-year storm in specific areas across the contiguous U.S. The curves help stormwater managers design interventions tailored to their region’s risk of heavy flooding during major storms.

Existing IDF curves, however, assume that rainfall amounts do not change over time. Much of the underlying data behind even the most recent IDF curves are more than 50 years old.

“Infrastructure that has been designed to these commonly used standards is likely to be overwhelmed more often than it is supposed to be,” Wright said.

Climatologists are largely in agreement that heavy rainfall from storms has been on the rise over the last few decades, with precipitation volumes increasing by up to 70% in some areas of the U.S. since the 1950s. This July, NOAA reported that 2019 was the wettest year on record in the contiguous U.S. for the third consecutive year. More than any other factor, the cause of the increase is thought to be climate change, which enables clouds to absorb more evaporation and produce more precipitation.

IDF curves not only fail to consider how the definition of a 100-year storm is changing in many parts of the U.S. in response to changing precipitation norms, but also how land-use and development trends have affected flood risks over the last half-century, the researchers write.

“We really need to get the word out about just how far behind our design standards are from where they should be,” Wright said.

Studying the disparity

To get a sense of the disparity between what was considered a 100-year storm in the mid-20th century and today’s severe rainstorms, the researchers pored over 67 years of records from more than 900 weather stations across the U.S. The analysis uncovered many storms with intensities surpassing what would be considered a 100-year storm in nearly all U.S. regions.

The U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports that 2019 was the wettest year on record in the U.S. for the third consecutive year. As shown here, heavy rainfall particularly on the East Coast has become far more frequent over the last 30 years. Current design standards for stormwater infrastructure fail to consider these changes, write researchers of a new study. NOAA

In the northeast U.S., for example, extreme rain events occurred 85% more often in 2017 than they did in 1950. In West Coast states, extreme storms appeared 51% more often in 2017 than in 1950.

In some parts of the country, infrastructure designed to withstand 100-year storms based on mid-20th century data today face storms that exceed their runoff management capacity up to 2.5 times more frequently, the researchers conclude.

“Though trends in rainfall extremes have not yet translated into observable increases in flood risks, these results nonetheless point to the need for prompt updating of hydrologic design standards, taking into consideration recent changes in extreme rainfall properties,” the team writes in their study.

Read the full study, titled “U.S. Hydrologic Design Standards Insufficient Due to Large Increases in Frequency of Rainfall Extremes,” in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.