According to the World Health Organization, lack of access to clean water affects 1 in 3 people in Africa. The United Nations has developed a new smartphone app, RWH Africa, to help promote rooftop rainwater harvesting and non-potable reuse. Photo courtesy of 2229018/Pixabay.

According to the World Health Organization, lack of access to clean water affects 1 in 3 people in Africa. However, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the continent experiences enough rain to satisfy the demands of roughly 9 billion people – assuming enough infrastructure is in place to capture and treat it.

Particularly for the 63% of Sub-Saharan Africans living in rural areas unserved by centralized water treatment systems, harvesting rainwater from rooftops is a useful way to conserve drinking water. Because rain captured from rooftops rather than ditches or roadways runs a lesser risk of containing pollutants, harvested rainwater can be used for irrigating crops, contributing to food security. It also reduces burdens on women and children, who collectively spend about 16 million hours each day traveling back and forth to the nearest clean water source, according to estimates from the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

Building basic, household-scale rainwater systems need not be an expensive or technically demanding process. These systems do, however, require site-specific planning and an idea of where to begin. RWH Africa, a new app available on smartphones and web browsers, provides this information to rural Africans interested in harvesting rainwater.

How it works

RWH Africa, developed by UNEP and UNESCO, asks users to report their nearest city, the area of their roof, the amount of impervious space on their property, and the daily water needs of their household.

Combined with data from more than 3,500 rainfall records from weather stations spread throughout the continent, the app uses this information to estimate the amount of rainwater the users can harvest from their roof with a harvesting system. It also recommends the amount of storage space the system should contain to ensure non-potable water supplies meet each specific household’s needs.

“This app is practical for individuals as well as communities, local governments, and other actors who are planning to install rainwater harvesting systems in Africa,” said Juliette Biao, director of UNEP’s Africa office, in a release. “The app is a concrete example of how science and innovation can be packaged to solve day-to-day needs of households in Africa.”

In addition to personalized system guidance, the app also offers a series of 14 short, animated videos produced by UNESCO that provide lessons on how to reuse captured rainwater, how to estimate project costs and locate materials, and how to avoid common construction pitfalls. The videos, as well as the rainwater harvesting calculator, are currently available in English, French, and Swahili.

With a version already available for Android on the Google Play Store and an Apple iOS version in the works, users already are using the app to achieve real-world results, according to a UNEP news release.

“Water harvesting has benefited our community where women have played a key role in constructing water tanks,” said Ann Kiria, chair of a Kenya-based women’s group, in the release. “With the knowledge we have acquired [from RWH Africa], building a water tank to harvest rainwater is no more out of reach.”

An example from Algeria

According to geopolitical analysts at Stratfor (Austin, Texas), rapid urbanization and overexploitation of natural water sources in Algeria have caused alarming water shortages in recent years. In Djanet, an oasis city on the outskirts of the Sahara Desert in the southeastern part of the country, the average annual rainfall is just 14.6 mm (0.57 in.), with no month averaging more than 3 mm (0.12 in.) of rain, according to figures from the World Meteorological Organization.

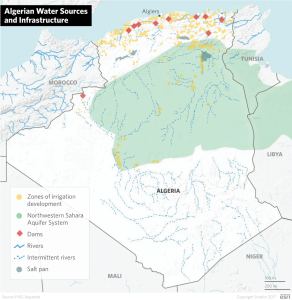

In water-stressed Algeria, natural water sources are unevenly concentrated in the nation’s north, while Algerians living south of the Sahara Desert often must travel long distances to ensure their family’s daily water security. The RWH Africa app provides site-specific guidance to these households on how to adopt rainwater harvesting as a means of supplementing precious water supplies. Photo courtesy of Stratfor (Austin, Texas).

Because as much as 30% of the Algeria’s centralized water supply is lost to leaks during distribution through its aging conveyance systems, capturing water from the nation’s few annual showers can be a crucial route to water security.

Consider a rural home near Djanet surrounded by pervious sand and gravel with a roof measuring 6 m (20 ft) by 9 m (30 ft). Two people live in the house, using a total of 240 L (63 gal) of water per day – just below Algeria’s average per capita water use in 2011.

According to the RWH Africa calculator, to provide a reserve of water that would meet the couple’s needs for up to 3 days during times of scarcity, the homeowners should construct a rainwater harvesting system with 1440 L (380 gal) of storage capacity. The couple should expect to harvest up to 952 L (251 gal) of rainwater per average storm, based on data from weather stations in Djanet.

The app also provides basic diagrams, showing how the homeowners could construct and arrange basic downtake pipes, sand or sedimentation filters, and storage tanks to maximize their rainwater capture.

The app provides data for major cities in all 54 African countries.