A joint report by the World Bank Group (Washington, D.C.) and World Resources Institute (Washington, D.C.), Integrating Green and Gray: Creating Next-Generation Infrastructure, calls for green infrastructure to become a common part of the infrastructure planning process. It details how green infrastructure systems can work alongside gray infrastructure systems to expand benefits, reduce costs, and bolster climate-change preparedness. World Bank Group/World Resources Institute.

Green infrastructure often requires more frequent upkeep and maintenance than gray infrastructure, generally entails more financial risk, and its effectiveness largely depends on its location. However, a newly released joint report by the World Bank (Washington, D.C.) and the World Resources Institute (WRI; Washington, D.C.) offers a new perspective on how to increase green infrastructure’s viability: by using it alongside gray infrastructure.

According to Integrating Green and Gray: Creating Next-Generation Infrastructure, a 140-page report released on March 21, supplementing gray stormwater infrastructure with activities that enhance natural landscapes can provide a wider array of benefits at a lower cost than either green or gray infrastructure would deliver separately. The report outlines how water professionals, public officials, and budget managers can create and support effective green–gray treatment systems, drawing on a range of real-life examples from World Bank-funded projects.

According to Greg Browder, the World Bank’s global lead for water security and lead author of the report, “21st century challenges require innovative solutions and utilizing all the tools at our disposal. And integrating ‘green’ natural systems like forests, wetlands, and floodplains into ‘gray’ infrastructure systems shows how nature can lie at the heart of sustainable development.”

Green infrastructure gains global credibility

Supplementing gray infrastructure with appropriately designed and managed green infrastructure can sharply reduce overall project costs, enhance the quality of service that gray infrastructure provides, and act as an important redundancy measure to protect vulnerable waterways.

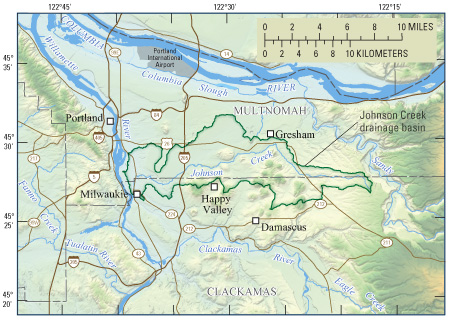

For example, the report cites a project in Portland, Maine, where watershed managers saved up to $155 million over 20 years by scrapping a planned water filtration facility in favor of restoration activities focused on local forests that achieved the same filtration benefits. Likewise, a network of urban wetlands and stormwater parks throughout Colombo, Sri Lanka, promotes runoff infiltration and capture, easing burdens on the city’s gray infrastructure systems and increasing its treatment capacity for wastewater. In the Philippines, coastal mangroves, coral reefs, and other natural landforms protect low-lying gray treatment systems from sea-level rise, preventing an estimated $1 billion each year in damages.

Green–gray treatment systems also are thought to be more attractive to investors than projects based on one type or the other, the authors write. Because green infrastructure usually provides benefits reaching further than stormwater treatments — that is, expanded wildlife habitat, higher property values, and climate change moderation — projects that incorporate green infrastructure appeal to private investors seeking to make a positive social and environmental effects with their investment in ways that gray infrastructure projects may not.

Incorporating gray infrastructure elements also helps address financial risks, as the site-specific nature of green infrastructure often makes predicting cost-effectiveness difficult during the planning phase.

Many governments and development agencies now also offer financing programs to help spur green infrastructure design and construction. For example, Costa Rica’s Payments for Ecosystem Services Program dedicates a portion of all taxes from water and fuel bills, alongside grants and loans from interested investors, to expand and maintain natural habitats as a means of enhancing stormwater control. In the U.S., water utilities serving large municipalities are increasingly issuing environmental impact bonds – a specialized type of risk-based and time-bound financing agreement – to fund green–gray stormwater management projects on unprecedented scales.

Winning combinations

As the report describes, many stormwater management systems that incorporate elements of both green and gray infrastructure are already common. These include bioretention basins and rain gardens that work alongside traditional storm drains and pumps, using vegetation as coastal buffer crops alongside built infrastructure such as flood walls, and improving wetlands for natural filtration to ease burdens on gray wastewater infrastructure. Jeff Frederick/Water Environment Federation (Alexandria, Va.).

The report makes an exhaustive case for why water managers should consider implementing green–gray systems. It also provides guidance for navigating local policies and regulations around green infrastructure, understanding the fundamental differences between measuring the cost-effectiveness of green infrastructure versus gray infrastructure, and recommends a path forward for widening and accelerating green infrastructure adoption.

“If we help nature, then nature can help us – that’s the message of this report,” said Kristalina Georgieva, interim president of the World Bank Group. “Measures like replanting wetlands can shield cities from storms and flooding, and protecting forests improves watersheds. Infrastructure should make use of plants and nature to boost resilience and create a more livable environment.”

Authors describe several examples of common green-gray water management systems that offer important social and environmental benefits at costs well below what building comparable gray infrastructure alone would entail:

- Green urban flood retention measures, such as bioretention basins and rain gardens, collect and store stormwater and reduce drainage and pumping requirements for gray storm drains, pumps, and outfalls.

- Improving agricultural soils’ water storage capacity can reduce inflow to irrigation and drainage canals, increasing their longevity while reducing demands for irrigation.

- Planting or expanding mangrove forests along coastlines can decrease wave energy and reduce storm surge, enabling smaller flood walls and embankments to prevent coastal flooding.

Read the full report at http://bit.ly/GI-report.