What happens when a hurricane sends fresh rainwater — up to 124.9 trillion L (33 trillion gal) of it — into the saltwater ocean? In the case of normal-sized storms, the rainwater, which is less dense than saltwater, typically sits atop the ocean in a distinct “blob,” which generally mixes into the ocean within hours or days.

However, the massive influx of freshwater that Hurricane Harvey delivered to the Gulf of Mexico in late August presents a different and unprecedented case. Now that the storm has passed, Gulf Coast researchers are venturing into the ocean to study the immense layer of freshwater that still, as of November, has not been absorbed by the sea.

From Aug. 25 through Aug. 29, Hurricane Harvey tore through the Gulf of Mexico, sending winds up to 209 km/h (130 mi/hh) and dropping up to 124.9 trillion L (33 trillion gal) of rainwater throughout many parts of Texas. Through coastal Texas’ many roadways and bayous, much of this rainwater ended up in the Atlantic Ocean. Researchers are now venturing out into the gulf to study the ecological effects of this unprecedentedly massive influx of freshwater into saltwater. U.S. Navy

Reading the reefs

In September, when the freshwater blob was still fresh, an automated buoy network reported that water salinity had suddenly dropped by 10% near Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, which sits about 161 km (100 mi) off the coast of Galveston, Texas. The signal indicated that freshwater from Hurricane Harvey had spread far beyond Texas’ shores, but offered little information about how the salinity shift might affect the sanctuary’s ecosystem.

In late October, a team of ocean researchers from Texas A&M University (College Station), Rice University (Houston, Texas), the University of Houston (Clear Lake, Texas), and Boston University visited the sanctuary in search of irregularities.

Texas A&M oceanographer Kathryn Shamberger and Rice University marine biologist Adrienne Correa focused on the freshwater’s effects on coral reefs. Correa told Rice News that Harvey floodwaters could have devastated the Flower Garden Banks reefs if the freshwater plume had flowed directly over them. However, she added that exploratory dives in three spots had not uncovered any evidence that the reefs had experienced mass die-off because of the salinity drop.

Tiny organisms, huge risks

Steve DiMarco and Lisa Campbell, both ocean researchers with Texas A&M, are focusing their attention on how the addition of freshwater might affect microorganisms and the growth of hypoxic zones, which could spell catastrophe for the marine environment if left unchecked.

“The freshwater sitting on the salty water cuts off the oxygen from the atmosphere getting into the ocean, and then you get the dead zone,” DiMarco explained to The Atlantic.

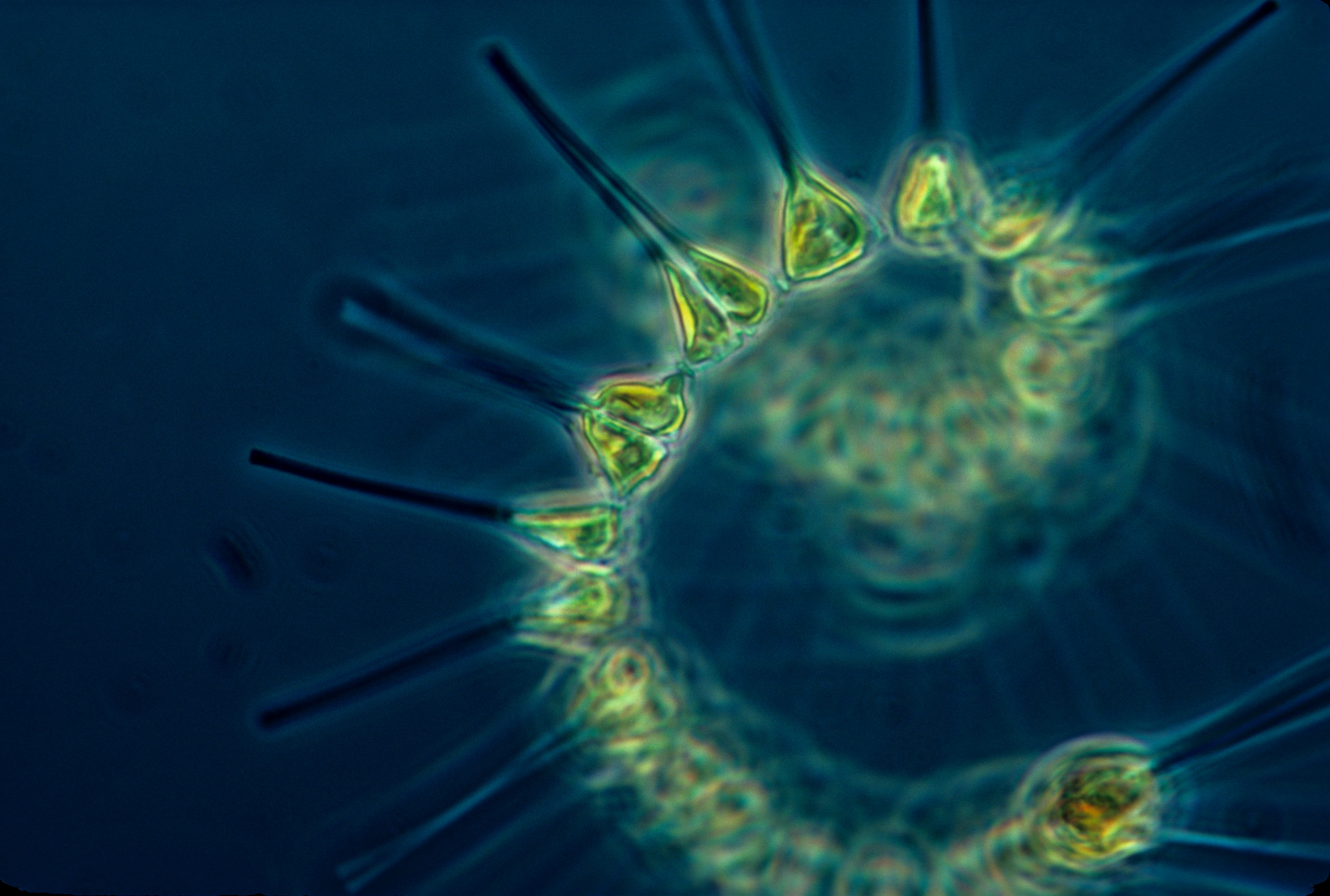

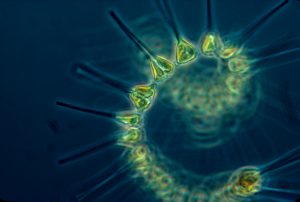

Texas A&M University (College Station) oceanographer Lisa Campbell received a Rapid Response Research grant from the National Science Foundation to study Hurricane Harvey’s effects on phytoplankton in the Gulf Coast. Phytoplankton constitutes the foundation of the marine food chain and fluctuations in its composition or concentration can have dramatic effects for larger aquatic organisms. U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The full extent to which Hurricane Harvey has affected the Gulf’s oxygen content requires ongoing investigation.

Likewise, Campbell is examining how the influx of freshwater might affect the Gulf’s long-term phytoplankton ecology. Her ongoing work is supported by a Rapid Response Research grant from the National Science Foundation.

“Previously when we see slugs of freshwater, it changes the type of phytoplankton that grow,” Campbell said.

Because phytoplankton and other micro-organisms are at the bottom of the marine food chain, these types of shifts could have effects that reach the entire ecosystem. Campbell and her team use data about the concentration of different phytoplankton species along the Gulf Coast to identify the physiological reactions they exhibit in response to immense floodwaters. While this information helps researchers understand Hurricane Harvey’s effect, the same data also is useful for resiliency planning as experts expect climate change to prompt more frequent and more intense rainstorms, Campbell told Texas A&M.

According to DiMarco, the ocean is not expected to absorb the massive plume of freshwater left behind by Harvey until wintertime, when more intense winds stir up the ocean.