November 2015 marks the 25th anniversary of the Phase I Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System program, promulgated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1990. Compared to the modern wastewater profession — an endeavor more than a century old ― stormwater management is a young discipline. While the sector is still maturing, a primary lesson learned over the last 25 years is that managing stormwater is very different from managing wastewater.

Geoff Brosseau, executive director of the California Stormwater Quality Association (CASQA) and the Bay Area Stormwater Management Agencies Association (BASMAA) shared his insights on trends and future shifts in stormwater quality management. As the leader of both a state and regional association, Brosseau focuses on training professionals, helping the sector mature, and charting a new path that takes stormwater on its own course, differentiated from its wastewater roots.

The Architect and the Builder

As state regulators across the U.S. began to launch stormwater permitting programs in the early 1990s, the sector had limited knowledge of how to manage stormwater to improve water quality.

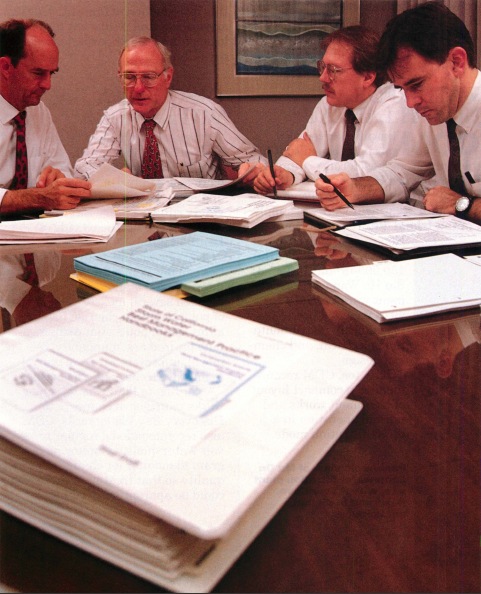

Authors of the California Stormwater BMP Handbooks, an early product of the California Stormwater Quality Task Force, hard at work. From left, Mack Walker, Larry Roesner, John Aldrich, and Geoff Brosseau. Not shown Gary Minton. Image provided by Geoff Brosseau

The California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) turned to the Stormwater Quality Task Force, an earlier version of CASQA formed in 1989 and composed of a small group of flood control agencies. The group became an official advisory body to SWRCB, and helped to establish the state’s new permitting program.

“We met monthly in a basement room below the tarmac at the Sacramento airport,” Brosseau said. “You could smell the jet fuel when the wind blew the wrong way.”

Since its early beginnings as an SWRCB advisory group, CASQA has grown into a statewide association. Yet it still helps with the development and implementation of California’s stormwater permitting programs.

For instance, the association is providing training on California’s industrial stormwater permit, which goes into effect in July. SWRCB turned to CASQA after the association developed training for the state’s 2009 construction general permit. This earlier training course qualifies professionals to create Storm Water Pollution Prevention Plans (SWPPP) and operate construction sites, and has resulted in more than 6000 qualified SWPPP practitioners and developers.

Valuable to CASQA’s efforts is the group’s relationship with SWRCB — a relationship that is more partnership than regulatory affiliation. “We have tried to keep that early culture,” Brosseau said. “It is more constructive and productive.” He likened the relationship to one between an architect and a builder. The state is the architect that designed the regulations, but the permittees and local agencies are the builders, the ones implementing the regulations. “When we suggest different approaches that will be easier to implement, it is like the builder coming back to the architect with thoughts,” he said.

CASQA is an organization composed of stormwater quality management organizations and individuals, including cities, counties, special districts, industries, and consulting firms. With its municipal members issuing permits to construction and industrial members, “you may think this could cause some fiction,” Brosseau said. “But everyone is pulling oars in the same direction.” There may be some disagreement in approaches, but the groups find that they can work together quite well and leverage each other’s knowledge.

Brosseau also leads BASMAA, a regional association with similar objectives. The group promotes consistency in stormwater permit compliance as well as efficient use of public funds through a consortium of the eight countywide urban runoff programs in the San Francisco Bay Area. BASMAA represents 96 agencies, including 84 cities and 7 counties.

In addition to his association work, Brosseau also has consulted with more than 25 municipalities throughout California to develop and implement virtually every aspect of their stormwater programs.

After his 25 years of working in the stormwater sector and 25 years since the passage of the Phase I regulations, “I think we are on the cusp of a new generation of permits and solutions,” Brosseau said.

Stormwater is Not Wastewater

Through their experiences, California permittees have found that some requirements work well for stormwater quality management, while others are not as effective. Brosseau has found that the underpinning of most critiques about stormwater permits and regulations is the expectation that stormwater can be treated or addressed like wastewater.

Stormwater is a very different kind of discharge, he said. “Though stormwater is called a point source on paper that does not change its nature or the fact that it really is a nonpoint source flow,” Brosseau explained.

One key difference is that wastewater flows through a closed system with known connections. It is therefore possible to calculate, fairly consistently, the amount of water a water resource recovery facility will receive.

In contrast, stormwater is harder to control and manage. “We can build pipes and drains, but we never know when or how much rain will come,” Brosseau said. In addition to volume planning challenges, municipalities also have little control over pollutants generated in the watershed and have a limited number of cost-effective management tools at their disposal.

Human actions — from product packaging and large-scale construction down to mowing a lawn or picking up after pets — all affect stormwater quality. “Storm drains are at the downstream end of all of society’s polluting behaviors,” Brosseau said.

Now that the fundamental differences between stormwater and wastewater have been recognized, Brosseau has called for action. “It is like being on an oil tanker headed in a slightly wrong direction. Once you realize your bearing is off, you can’t turn it fast enough because of the inertia built up over 25 years,” he said.

In January, CASQA released its Vision and Strategic Actions for Managing Stormwater in the 21st Century. Built on the premise that stormwater is different than wastewater, the vision calls for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of stormwater quality management through regulations that clarify stormwater as a nonpoint source.

Among several goals, the vision calls on EPA and state agencies to articulate critical Clean Water Act priorities, promote statewide consistency in policy and permitting frameworks, and create funding opportunities. Another key component of the vision is treating stormwater as a vital resource — an idea that is especially significant for drought-prone California. The vision urges the state to plan for stormwater harvesting and to eliminate constraints on stormwater use.

Among several goals, the vision calls on EPA and state agencies to articulate critical Clean Water Act priorities, promote statewide consistency in policy and permitting frameworks, and create funding opportunities. Another key component of the vision is treating stormwater as a vital resource — an idea that is especially significant for drought-prone California. The vision urges the state to plan for stormwater harvesting and to eliminate constraints on stormwater use.

A key strategy for rethinking runoff as a resource is protecting its quality, particularly through the use of what Brosseau calls true source controls.

True Source Controls

As a marine biologist, Brosseau started his career working for aquaculture startup companies. For nearly 10 years, he helped farm kelp and other seaweeds for chemical extracts used to generate energy and pharmaceuticals.

He finds the stormwater profession similar in that one has to be a jack-of-all-trades. One day a stormwater manager may be dealing with pesticide, construction, or trash issues, and the next he or she may be conducting an industrial inspection or writing a report.

Brosseau attributes this need for flexibility to the fact that everything ends up in stormwater eventually. And so every stormwater problem also has multiple potential collaborators. “A very typical approach to a stormwater problem is asking where does it start, and who is involved in the pathways, and do they have a way of helping us control it?” Brosseau said.

Source control, which Brosseau focused on for the first 15 years of his stormwater career, is his primary area of expertise. Operational source controls, such as inlet covers or street sweeping, focus on keeping pollutants out of stormwater. But similar to the directional difference between compass-north and true-north, true source controls focus on the original source or the existence of the pollutant.

An expert on best management practices (BMPs), Brosseau helped to author the 1993 and 2003 California Stormwater BMP Handbooks as well as the 1998 manual, Urban Runoff Quality Management, published by the Water Environment Federation and the American Society of Civil Engineers.

“Many stormwater BMPs are fairly weak – begging people to pick up after their dogs or not to over fertilize, for example,” Brosseau said. However, true source control is a “super BMP,” as is green infrastructure, he says. Green infrastructure is the other side of the source control coin in that it reduces the amount of runoff that potentially can mix with pollutants.

While they do solve the problem, these super BMPs can take a long time to come to fruition and require the work of partners at many levels.

“I am a real proponent of working on issues at the right geographic scale — regional, state, and national,” Brosseau said. This is where his association work with BASMAA and CASQA comes in. For example, these groups helped to address California’s issue of copper in brake pads, which are the largest source of copper in stormwater. The issue was first brought to light in the San Francisco Bay Area. BASMAA became involved at the regional scale, and began working with the SWRCB, CASQA, and EPA.

CASQA helped the state build legislation regulating the amount of copper in brake pads. In 2010, the law passed in California alongside similar legislation in Washington State. This signaled a market shift for the automotive industry nationwide, and in January of 2015, EPA and others launched the Copper-Free Brake Initiative, a voluntary agreement to reduce the use of copper and other materials in motor vehicle brake pads.

“Our business is about keeping pollutants out of stormwater,” Brosseau said. “Once they are mixed, you spend a lot of time treating them. It is better to not let them mix in the first place, and it is even better to reduce the amount of pollutants out there.”

For instance, it is nearly impossible to remove all copper from runoff, but just by focusing on reducing the metal in brake pads, California may decrease copper in stormwater by an estimated 61%.

Another source control success is the removal of about 90% of lead from gasoline in the early 1980s. Stormwater data from the Nationwide Urban Runoff Program shows a corresponding 90% drop in lead in runoff samples. Similar decreases were seen in lead in the air and lung-related disease across the U.S.

In a controversial approach, SWRCB now is tacking litter with an amendment passed in April 2015. The amendment is very heavy on using treatment in the form of trash capture devices rather than pollution prevention. These devices are effective to a degree, Brosseau said, but it is important to recognize that focusing on treatment rather than behavioral changes puts the cost burden on the public and takes society in a less positive direction. The devices also do not address trash dumped or blown directly into a waterbody.

“Littering is probably our oldest polluting behavior as a species, creating a problem we have yet to solve. Yet it is a problem that is falling to stormwater professionals,” Brosseau said. “We don’t know if we can solve it. The issue of litter is a huge challenge and one that is very capital intensive.”

***

According to Brosseau, the stormwater quality sector is at a threshold, a turning point that will lead to a new generation of permits that allow the sector to operate more effectively and efficiently. As stormwater professionals heed the lessons of the past in planning for the future, 25 years of experience will help the sector better use stormwater as a resource, implement more super BMPs, and address shortcomings caused by modeling stormwater requirements after wastewater.