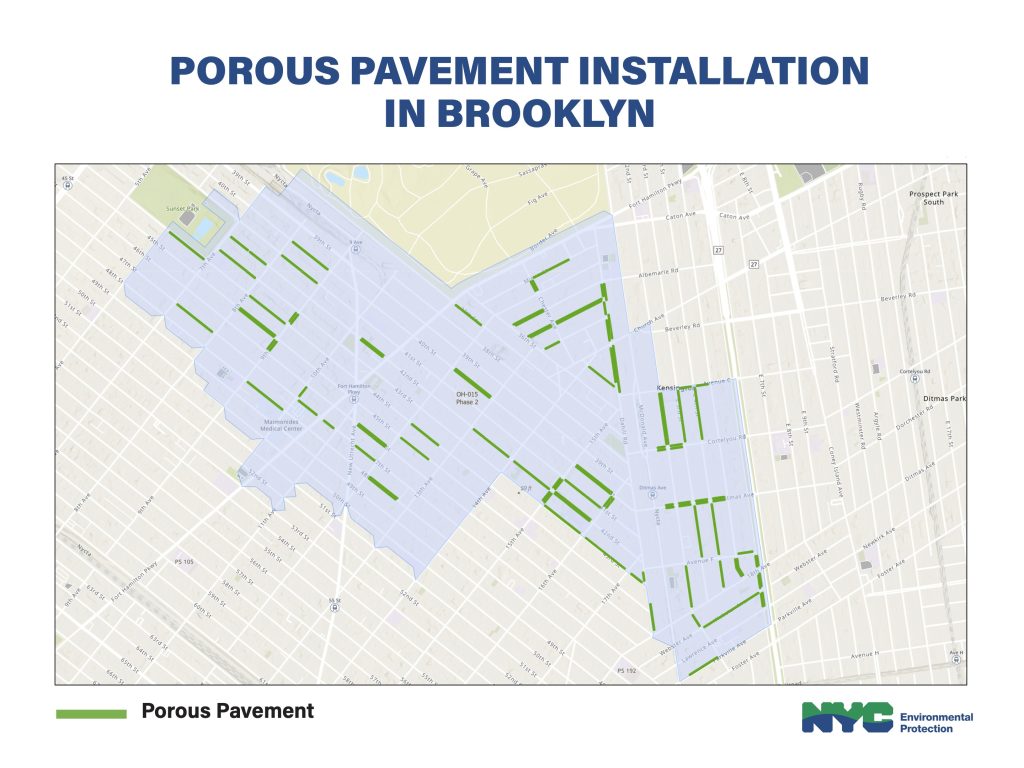

New York City is taking a significant step toward better stormwater management by installing 11 km (7 mi) of porous pavement along roadways in Brooklyn. This initiative, recently announced by Rohit T. Aggarwala, Commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and Tom Foley, Commissioner of the Department of Design and Construction (DDC), aims to reduce flooding and combined sewer overflows (CSO). Completion of the USD $32.6 million project is expected in fall 2025.

“Climate change is bringing with it rainstorms that can overwhelm our sewers and cause flooding across the five boroughs, which is why we are investing in tools that will divert rainwater away from the sewer system, such as porous pavement,” said Aggarwala in a release. “Brooklyn got hit particularly hard by Tropical Storm Ophelia last September and this new porous pavement will help to ease pressure on the sewer system and protect residents during future storms.”

The Perks of Going Porous

Porous pavement, unlike traditional asphalt, naturally infiltrates stormwater into the ground, reducing the volume of water entering collection systems. This helps prevent flooding, sewer backups, and CSOs — a chronic nuisance for the 60% of New York City operating under a combined sewer system. The porous pavement will sit along the curbline of streets, where stormwater naturally runs. After absorption, the runoff then will flow toward catch basins.

“This is the biggest porous pavement installation this city has seen, and it will prevent millions of gallons of stormwater from overwhelming the sewer system annually,” said Foley. “With this DDC design, we will implement porous pavement panels in precise areas, allowing for the absorption of stormwater, before they overwhelm catch basins. It will also save time and money, since porous pavement installations can prevent flooding without the need of going underground and expanding sewers.”

Pre-construction soil samples will determine whether the ground can absorb stormwater effectively. The curbline will be removed along approved roadways, and crews will place drainage cells and stones nearby to aid in stormwater drainage and storage. Finally, they will add the porous concrete on top. The specially manufactured concrete slabs are designed to withstand the weight of vehicles and will not affect street parking.

While DEP has tested various types of porous pavement in different boroughs over the years, this Brooklyn project represents the first large-scale implementation.

Later this year, additional contracts are expected to bring porous pavement to more Brooklyn neighborhoods and communities in the Bronx. Further planning is underway to extend this green infrastructure solution to neighborhoods in Queens.

Part of a Bigger Picture

Across New York City, 12,070 km (7,500 mi) of collection systems and 150,000 catch basins are the life force of the city’s drainage system. However, the porous pavement project is part of a larger, long-term investment resulting from a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) 2012 CSO Consent Order aimed at updating an aging system. The order originally required the city to reduce CSO volume by 6.32 billion L (1.67 billion gal) annually by 2030 via USD $1.4 billion in green infrastructure projects, leading to the formation of NYC’s Green Infrastructure Program, responsible for more than 13,000 green infrastructure projects — the largest program of its kind in the U.S.

In 2023, DEP and NYSDEC signed a modification to the Consent Order, called the 2023 Citywide Green Infrastructure Modification, which increased the green infrastructure project budget to USD $3.5 billion. It also updated the original CSO reduction timeline from 2030 to 2040 and expanded the definition of green infrastructure to include site- and neighborhood-specific practices such as rain gardens; larger-scale projects such as stream daylighting; as well as practices to mitigate risks from events such as cloudbursts.

“We are working closely with local communities and our partners at NYSDEC to ensure that every waterway is as healthy as it can be, while also building the type of infrastructure that can increase our resilience to the more intense storms that are caused by climate change,” Aggarwala said.

Top image courtesy of NYC Water

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michelle Kuester is a staff member of the Water Environment Federation, where she serves as Associate Editor of Stormwater Report and Water Environment & Technology magazine. She can be reached at mkuester@wef.org.