New York City occupies approximately 775 km2 (300 mi2) of space, more than half of which features impervious surfaces that promote flooding during heavy storms. The city faces the possibility that severe storm events will become as much as three times more likely to occur in 2050 than they did in 2015 due to the effects of climate change. Therefore, leaders of the largest city in the U.S. are taking aggressive action to improve flood mitigation capabilities.

The city’s approach prescribes a range of investments in the coming years that focus on both infrastructure and information. These steps are detailed in an action plan released by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYC DEP) in September 2022.

In January 2023, the city announced major expansions to two stormwater initiatives intended to enhance resilience in all five boroughs: the Cloudburst Program and the FloodNet system.

- The Cloudburst Program, developed in partnership with the City of Copenhagen, Denmark, constructs neighborhood-scale clusters of green and gray infrastructure that cooperate to convey runoff to strategic points during major storms. The program will receive an additional USD $400 million to support projects in four new neighborhoods.

- FloodNet, a system of real-time flood-monitoring sensors already active in all five New York City boroughs, will receive an additional USD $7.2 million that will enable the network to multiply its current number of sensors by a factor of 15.

Cooperation on ‘Cloudburst’ Control

Roughly 60% of New York City is served by combined sewer systems that convey both wastewater and stormwater, according to NYC DEP estimates. Particularly in densely urbanized, inner-city neighborhoods served by combined sewer systems, heavy storms frequently overwhelm the collection systems that are already overburdened by a high concentration of residents, causing chronic flash flooding.

In Copenhagen, stormwater professionals often refer to the short, intense surges of rainfall that most commonly cause flash flooding and combined sewer overflows (CSOs) as cloudbursts. During the last few decades, Copenhagen has demonstrated success in using ambitious, extensive, and unconventional infrastructure designs to control cloudbursts. The city’s approach not only includes traditional elements like rain gardens and bioretention cells, but also subsurface pipe systems, restored urban wetlands, and even entire streets rebuilt with slopes and curves meant to convey runoff to specific points. These green and gray features work in tandem to relieve burdens on combined sewer systems on the neighborhood scale, while also providing new, attractive community amenities.

Seeking to learn from Copenhagen’s experience, NYC DEP formed a partnership with Copenhagen-based engineering firm Ramboll in 2016 to identify opportunities for similar projects in New York City. The partnership published a study about their findings in 2017, identifying a site in Queens’ South Jamaica neighborhood as the best candidate for a pilot project.

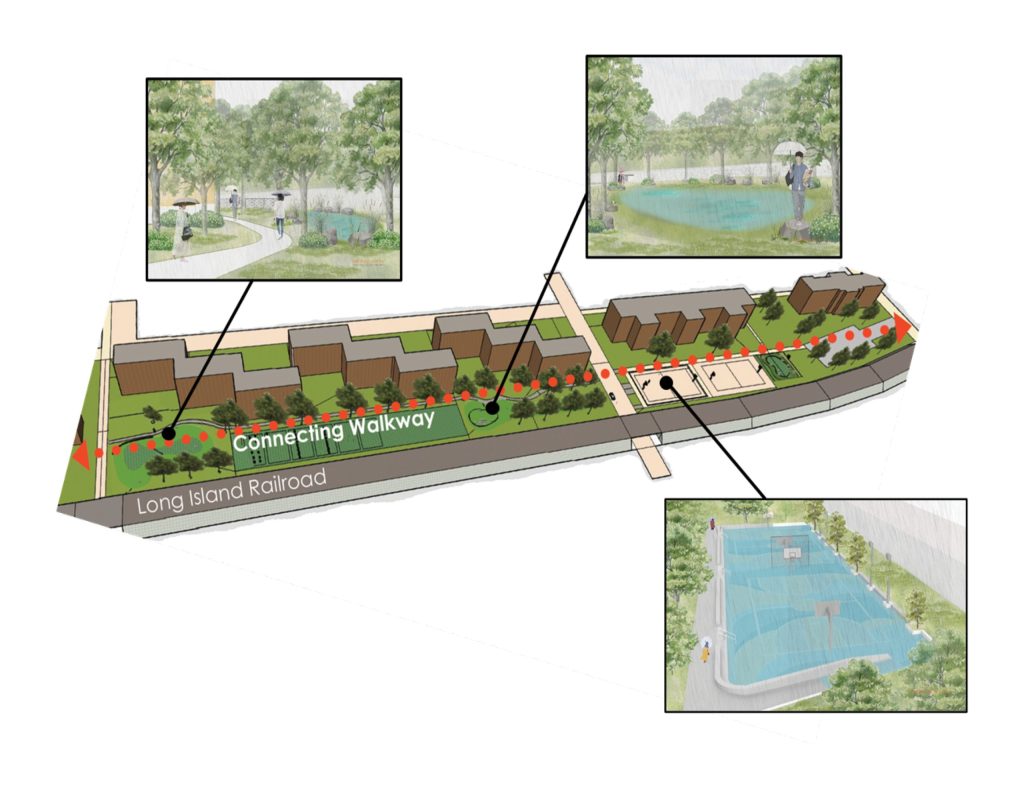

After a lengthy design process, construction on the site will begin this year, New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced in September 2022. The initiative, which marks the official commencement of New York City’s Cloudburst Program, will invest up to USD $5 million in South Jamaica to channel stormwater from around the neighborhood toward two open, grassy areas, which will themselves receive new vegetation and subsurface features to increase their temporary storage capacity. Plans also call for the reconstruction of an existing basketball court at a lower, sunken elevation, which will provide additional detention capacity during cloudbursts. In all, NYC DEP expects the new features to increase local stormwater management capacity by approximately 1.1 million L (300,000 gal) — designed to eliminate flooding from today’s definition of a 100-year storm.

Under the Cloudburst Program, the design process is already underway for similar renovations targeting the St. Albans neighborhood in Queens as well as Manhattan’s East Harlem neighborhood. The newly allocated USD $400 million in municipal and federal funds, which Adams announced in January 2023, will enable the city to initiate the design process for four additional neighborhoods: Corona Park (Queens), Kissena Park (Queens), Parkchester (Bronx), and East New York (Brooklyn). NYC DEP expects construction in these neighborhoods to begin in 2025. More than two dozen additional neighborhoods are under consideration by NYC DEP for future projects, Adams described.

“This $400 million investment in stormwater management projects cement New York City’s status as a national and global leader in green infrastructure and shows our commitment to protecting New Yorkers from disastrous floods,” Adams said in a January release.

Casting a Wider FloodNet

In addition to socioeconomic and environmental justice concerns, a key factor in Cloudburst’s site-selection process is flooding data.

How often and how severely a neighborhood has historically experienced flooding, the location and frequency of existing flooding, and how those trends are poised to shift as climate change intensifies are all factors. To better provide this data, the City University of New York (CUNY), New York University (NYU), Brooklyn College, and the Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay partnered with various municipal agencies to introduce the FloodNet system in 2020.

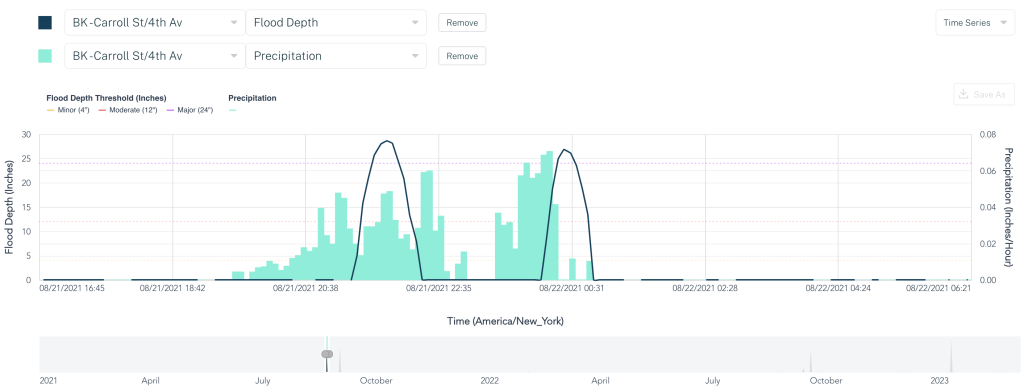

FloodNet partners install water-level sensors in strategic locations throughout the city. Each sensor is about 3 m (10 ft) from the ground and feeds real-time information on the timing and severity of flood events to a publicly accessible dashboard. The dashboard provides users remote access to minute-by-minute updates on floodwater depths as they change. The sensors also can discern whether the flood results from CSOs and overburdened storm drains or coastal storm surges, as well as how developing floods compare to historical events.

Users can explore, for example, the details of how Hurricane Ida caused record-breaking flooding in Brooklyn in September 2021, or how a new-moon tide compounded the effects of a winter storm in December 2022 to cause substantial coastal flooding in the Far Rockaway neighborhood of Queens.

Currently, FloodNet consists of 31 sensors. That number is already rising thanks to USD $7.2 million in new municipal funding announced in January. This funding will increase the number of monitored locations to 500 during the next 5 years. Network expansion already is underway, with the first new sensors installed in Staten Island scheduled to come online shortly.

“The city’s increased investment in FloodNet sensors will create an even more expansive, hyperlocal monitoring network that can alert New Yorkers in real time to dangerous flooding caused by intense rainfall,” New York City Chief Climate Officer and DEP Commissioner Rohit T. Aggarwala said in January. “This life-saving, innovative technology will help us better understand and prepare for future storms, plan and build more resilient communities, and design and implement infrastructure that will more effectively manage extreme weather.”

Top image courtesy of Alanna21/Pixabay

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.