Conventional wisdom says dams upstream from densely settled areas can keep flood-prone rivers from experiencing dangerous and costly floods by controlling when and how much water flows downstream. However, new research published in the journal Nature Communications shows that under certain hydrogeological circumstances, dams could instead increase downstream flood risks rather than mitigate them.

According to the new study, these ever-growing dunes that form along riverbeds downstream from dams could eventually pose obstacles to the flow of water, promoting flooding during high-flow conditions, such as a heavy storm.

“A coarser bed enhances the size of dunes. Dunes, in effect, act as sandpaper on the riverbed, enhancing friction and impeding the movement of water, and increasing resistance to flow,” explained Jeffrey Nittrouer, study co-author and Texas Tech University (Lubbock) geoscientist in a release. “As a consequence, water flows slow, which results in increasing flow depth and river stage, increasing flood hazard.”

Study authors emphasize that readers should not interpret from their findings that dams are counterproductive for flood control. Often providing other benefits such as drinking water, electricity, and irrigation supplies, many dams are also adequately equipped to address the flooding their region has historically experienced. However, the team’s finding that downstream flooding could become more likely as erosion extends and sediment sizes increase, coupled with more frequent and intense storms expected from climate change should give watershed managers a new angle to consider as they design new dams, Nittrouer explained.

“New dams are inevitable, but the planning and design of this infrastructure must be painted in a new light: the ability of future river channels downstream of dams to retain water,” Nittrouer said.

Bigger Sediments, Greater Risks

After a dam is established, downstream changes in erosion rates and sediment size can be observed almost immediately, researchers write. That was the case for the 154-m (505-ft) -tall Xiaolangdi Dam along China’s lower Yellow River, which was erected in 1999. As one of the most-studied rivers in the world, the researchers found more than 50-years-worth of available data on how such factors as average bed-sediment size, channel geometry, and flow speed changed after the dam’s construction. Abundant data both before and after the Xiaolangdi Dam’s construction made the surrounding area an ideal site to study the dam’s long-term effects on downstream flooding, authors write.

Studying patterns in the data led researchers to conclude that the downstream Yellow River’s ability to contain small floods increased after the Xiaolangdi Dam’s construction as the channel deepened with erosion. However, during larger flood events, the stretch downstream from the dam was more prone to spilling over than it was before the dam was built. The dam also affected downstream sediment sizes, which ranged from an average of 0.04 to 0.1 mm before the dam to an average of 0.3 mm since its construction.

The researchers used these insights to develop a numerical model characterizing the complex relationship between dams, stream-bed erosion, sediments, and ultimately flood risk. The model outputs a “suspension number” for river stretches downstream from dams that measures dune-driven resistance to water flow. If that suspension number falls within a certain range based on relative bed height and average sediment size, flooding is more likely during a high-flow event, the study proposes.

Although the researchers focused on the Yellow River, validating their model on data from other rivers revealed that its predictions of sediment size and dune behavior remained accurate for at least 80% of fine-grained, lowland rivers regardless of size or location.

“Our physically based model is validated by historical records to prove that after dam construction, channel bed grain size indeed coarsens, flow resistance increases, and, most importantly, these two effects combine to enhance river stage downstream of dams,” Nittrouer said.

Read the full, open-access study, “Amplification of downstream flood stage due to damming of fine-grained rivers,” in Nature Communications.

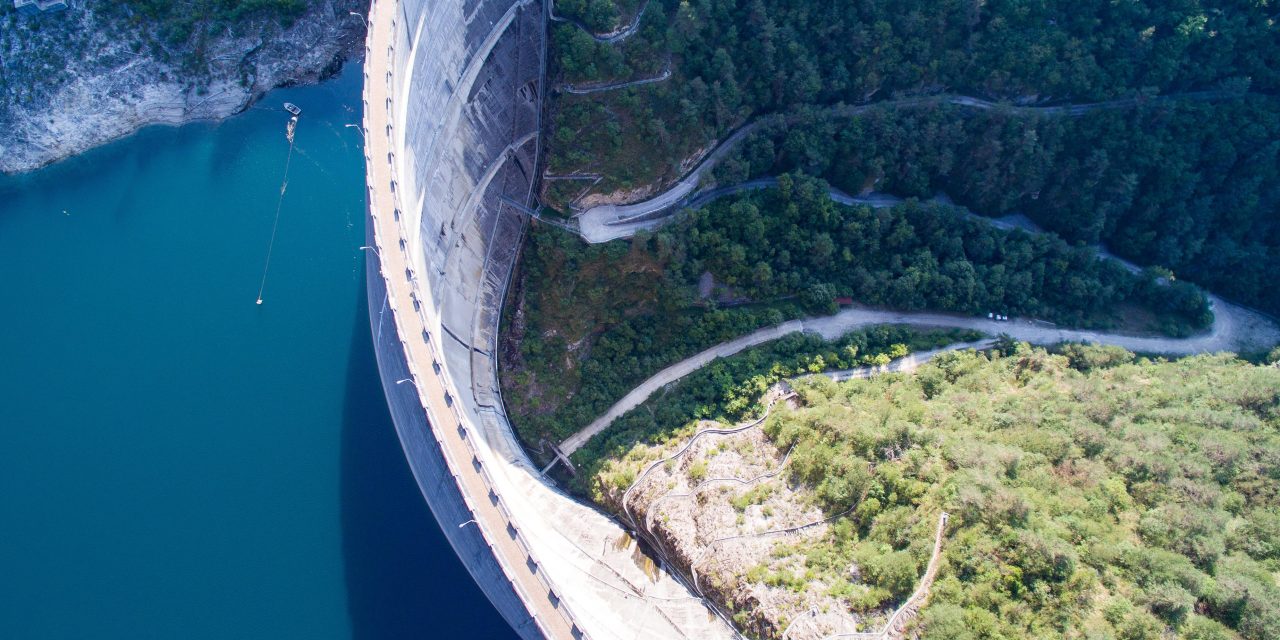

Top image courtesy of Thomas Ehrhardt/Pixabay

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.