Conventional wisdom dictates that the more impervious surface area a city contains, the more stormwater infrastructure will be necessary to compensate for the lost absorptive function of its natural green spaces. New research, however, subverts conventional wisdom about stormwater infrastructure, finding that if an urban watershed contains enough impervious space, no amount nor composition of stormwater infrastructure — green nor gray — will make a significant difference in curtailing runoff generation during intense storms.

According to the study, which involved researchers from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), Pennsylvania State University (PSU; State College), and Princeton (New Jersey) University, stormwater management funding would be better spent on measures to reduce impervious area coverage than on infrastructure projects that aim to mitigate runoff.

“Our findings contribute more evidence to the work of previous researchers suggesting that stormwater management is less effective at decreasing urban runoff than commonly is assumed,” said Jonathan Duncan, PSU hydrologist and study co-author, in a Penn State News release. “In these watersheds, we believe that the percentage of impervious surfaces may have greater influence on runoff volume than the percent of stormwater management coverage.”

Infrastructure vs. Imperviousness

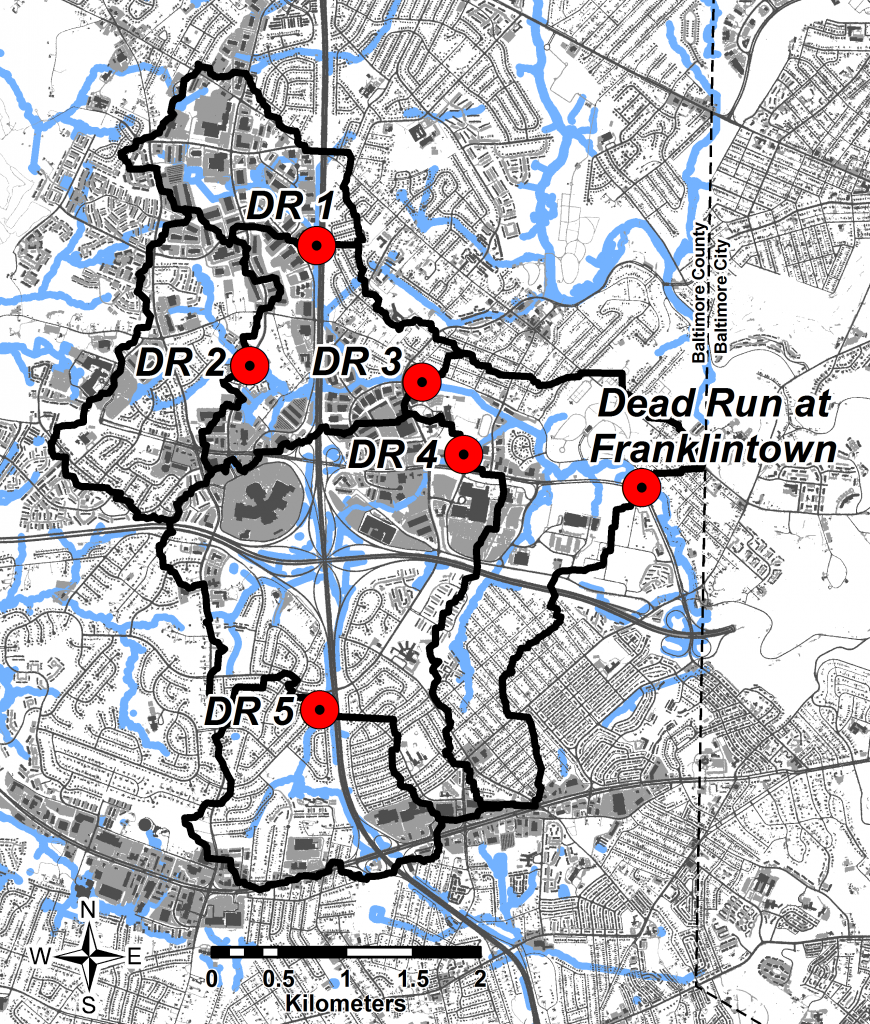

Maryland’s Dead Run watershed, comprising suburbs of Baltimore, features an extensive network of stream gauges and other environmental monitoring stations operated by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). With nearly 50% impervious area coverage over the 14-km2 (5.5-mi2) expanse, researchers described in their study that the Dead Run watershed was an ideal setting to study how runoff forms and behaves in impervious landscapes during severe rainfall events.

Splitting the Dead Run watershed into three focus areas served by varying amounts of stormwater management infrastructure, the research team sought to better understand runoff behavior in response to short-term, “pulse” rainfall events — those that deliver at least 96% of their total precipitation within 60 minutes. USGS streamflow data helped researchers select 19 pulse storms that occurred over the Dead Run watershed within the last two decades, recreating them via digital modeling to pinpoint how and when runoff formed within each sub-watershed.

According to the study, which appeared in the journal Hydrological Processes, the three areas of interest ranged in impervious surface coverage from 45% to 67%, and in sub-watershed areas served by stormwater management infrastructure from 3% to 61%. Importantly, existing stormwater management infrastructure across all three sub-watersheds was largely gray, including dry ponds and lined structures built for extended periods of detention. Green infrastructure, such as sand filters, infiltration trenches, rain gardens, and bioretention facilities, made up considerably less of total infrastructure coverage area in each sub-watershed, the study notes.

Despite major differences in runoff-reduction infrastructure coverage, modeling exercises revealed only slight differences in runoff volume, intensity, and timing between the sub-watersheds for each of the 19 storms. The finding, Duncan described, provides evidence that impervious area coverage is more important than infrastructure coverage when it comes to preventing runoff.

“No one wants to hear this, but we have a high level of confidence in our data and experimental design that reduced variability across sub-watersheds we studied,” Duncan said. “A few other studies have suggested this, but they were not conducted with the detailed, watershed-scale hydrology data we had. The bottom line is that we were not able to detect any difference in flows created by stormwater management.”

Consider with Caution

Contrary to their results, study authors caution readers against concluding that stormwater infrastructure — particularly green infrastructure — is ineffective. Lead author Andrew Miller of the UMBC Department of Geography and Environmental Systems emphasized that while the Dead Run watershed’s sensor coverage and impervious area provided an excellent setting to study urbanized watersheds, stormwater infrastructure coverage was neither diverse nor widespread enough to draw generalizable conclusions about its appropriateness for other watersheds. Additionally, the Dead Run watershed did not feature enough green infrastructure for conclusive analysis about its performance.

“I think there is actually a fairly common understanding about both the value of [green infrastructure] features and their limits,” Miller said. “They can work quite well until you get to higher rainfall amounts and intensities, but they don’t necessarily handle the biggest storm events so effectively.”

Several U.S. stormwater experts reacted to the study, praising its findings but reiterating the uses and benefits of green infrastructure not included within the scope of the paper.

Mark Doneux, administrator of the Capitol Region Watershed District (Saint Paul, Minnesota), described that many common types of green infrastructure do not primarily intend to reduce peak flows during heavy storms, but rather to purge sediments, bacteria, and other contaminants from stormwater before it becomes runoff. Virginia Roach, vice president of CDM Smith (Boston), agreed that the Dead Run watershed did not contain examples of green infrastructure large or widespread enough to support runoff mitigation, but that even the small amount of green infrastructure it contains helps benefit water quality in local streams and confers important environmental, economic, and health-related co-benefits to surrounding communities.

“Green infrastructure alone is not a flood control practice,” Doneux said. “Green infrastructure is a practice that is more directed toward water quality, and in time, with widespread applications, may begin to reduce peak flows.”

Fernando Pasquel, national director for stormwater and watershed management at Arcadis (Arlington, Virginia), indicated that the study did not provide information on the design standards, age, and condition of both gray and green infrastructure within the study area, noting that infrastructure measures of a certain age “are not effective for quantity or quality control,” and thus could have skewed the paper’s findings.

Scott Taylor, chair of the National Municipal Stormwater Alliance (Alexandria, Virginia), argued that much more than half of the study area would have to be served by green infrastructure to see meaningful results for peak-flow mitigation, adding that green infrastructure “is part of a more comprehensive solution” and best used as a supplement to gray infrastructure measures for flood control.

Read the study, “Assessing urban rainfall-runoff response to stormwater management extent,” in the journal Hydrological Processes.

Top image courtesy of PublicDomainPictures/Pixabay