According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF; Annapolis, Maryland), stormwater runoff is the only major source of pollution still on the rise in the 166,000-km2 (64,000-mi2) Chesapeake Bay watershed. As development continues across the six U.S. states touched by bay tributaries, runoff from paved, urban centers annually contributes immense amounts of nutrients, heavy metals, and other contaminants into the bay ecosystem. CBF estimates that at least 2.2 million ha (5.5 million ac) — approximately 15% of all land in the Chesapeake Bay watershed — consists of developed areas such as concrete roads, buildings, and parking lots. On each impervious acre, a single inch of rain generates about 102,000 L (27,000 gal) of runoff on average that eventually enter the Chesapeake Bay.

For those aiming to improve stormwater management without hindering urban development, parking lots are often an easy target for green infrastructure (GI). Parking lots typically feature vast impervious asphalt coverage and ample opportunities for GI such as permeable pavers, curb cuts, and bioretention planters. Most parking lots, however, are privately owned or supported by taxes, and require familiarity and buy-in from their owners for GI to flourish.

Over the past year, the Water Environment Federation (WEF; Alexandria, Virginia) Stormwater Institute partnered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Chesapeake Bay Trust (CBT; Annapolis; Maryland) to establish the Support for Innovative Approaches and Clean Water Technologies for Resilient Redevelopment grant program. The project provided free redesign services for two parking lots in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, creating state-of-the-art upgrade plans that reduce flood risks for lot owners and protect bay water quality while remaining useful for motorists.

From Parking Lot to Art Installation

Nestled in a densely settled suburb of Washington, D.C., the nonprofit performing arts center Joe’s Movement Emporium faces stormwater management challenges typical for the metropolitan environment.

The property, which consists of a large, single-story building adjacent to a 650-m2 (7,000-ft2), compacted-gravel parking lot, is nearly 100% impervious. Joe’s also sits near the foot of nearby Mount Rainier and frequently deals with inundation from downhill flooding during heavy storms. Brooke Kidd, founder and executive director of Joe’s, described how traditional approaches to flood management —such as gutters, pipes, and pumps — have failed to solve the property’s issue.

“The gutter on the front of the building along with a sump pump pipe spills onto a public sidewalk, which creates stains and icing. It’s a real nuisance to our neighbors and pedestrians that has mystified several contractors,” Kidd said.

Leadership at Joe’s engaged with WEF and its Resilient Redevelopment design partners, Designgreen (Washington, D.C.), Mary Gattis (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), and EcoLucid (Brookline, Massachusetts) — three consultancies with expertise spanning green infrastructure engineering, community engagement, and regulatory policy. The property’s constrained parcel above a high water table made Joe’s an excellent candidate for small-footprint GI that could enhance flood protection in existing spaces without requiring major excavation.

Engineers involved in the redesign first considered adding a layer of greenery above the performing arts center’s existing roof to prevent on-site runoff from reaching the parking lot. However, a structural analysis showed that the roof would not be able to bear the additional weight safely. They then visualized collecting runoff from rooftop gutters in a cistern behind the building, which would convey water through raised planters along the building’s sides into bioretention areas near the parking lot.

Ultimately, the final design called for a greater focus on the parking lot, opting for a series of suspended green roof trays hanging over parking spaces to simulate a shallow creek. At one end, the tray network would collect and divert stormwater from a silo-style rain barrel located on the roof and through elevated, building-side planters. On the other, it would release runoff from around the property into new bioretention areas at the front of the building. The design also identified a central driving lane traversing the parking lot as suitable for permeable re-pavement.

The modular planters above parking spaces and along exterior walls would enhance stormwater management and create a highly visible showpiece that aligns with the artistic and civic goals of Joe’s Movement Emporium, Kidd explained. The performing arts center previously developed a successful arts-based training program that has since evolved to teach students about ways to use their creative skills for environmental conservation.

“We have seen that our young adults equipped with digital media, story-telling and performing arts skills are much needed in the environmental field to tell the urgent story of the climate crisis,” Kidd said. “The message has to reach more, and I believe the arts can propel this effort.”

With the design phase completed, the CBT awarded Joe’s $30,000 in July 2020 to support the engineering phase as part of its Green Streets, Green Jobs, Green Towns Grant Program. Additionally, the grant supports a partnership between Joe’s and the National Green Infrastructure Certification Program (NGICP) to offer students access to GI-focused job training.

Making the Most of Existing Infrastructure

Although the Chesapeake Bay watershed contains only a handful of major metropolitan centers, it is dotted by countless suburban and rural communities. Urban sprawl and impervious area coverage also present challenges in these areas, which often run a higher risk of conveying nutrients from agricultural fertilizers into bay tributaries with insufficient stormwater management measures.

Aiming to create a repeatable and scalable model for flood-prone parking lots in suburban and rural environments, the Resilient Redevelopment team also selected Reservoir Park in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to receive a free, GI-focused redesign.

Lancaster is no stranger to the GI approach. In 2011, the city developed a forward-looking Green Infrastructure Plan, which outlined the area’s inherent vulnerability to nuisance flooding and the potential of GI to mitigate it. According to the city’s report, an aging combined sewer system alongside increasingly more frequent and intense storms mean that “each year, the City of Lancaster is responsible for about 1 billion gallons of polluted water flowing into the Conestoga River and eventually into the Chesapeake Bay” as a result of combined sewer overflows (CSOs). The report, containing more than 50 specific ideas for GI improvements around the city, notes that about 32% of impervious land in Lancaster consists of parking lots.

Reservoir Park is a popular destination for locals. The approximately 3,250-m2 (35,000-ft2) park features a basketball court, a roller hockey rink, a wading pool, and other amenities, served by an expansive, 54-spot parking lot. According to project documents, the proposed redesign would remove approximately 215 m2 (2,300 ft2) of impervious coverage from the parking lot while creating an additional 650 m2 (7,000 ft2) of new parking areas utilizing permeable pavers. The engineers envisioned an angled, parallel parking-spot configuration that would enable the lot to become more compact without sacrificing capacity, surrounding the lot with new, eye-catching bioretention areas featuring native plants.

Many park attractions are roofed, such as an approximately 150-m2 (1,650-ft2) pavilion and a nearby bike rental shop. During the redesign, project engineers viewed surrounding rooftops as an opportunity to capture runoff without downsizing the parking lot beyond the needs of its guests. The team selected a series of modular and low-cost rain tanks outfitted with controlled release valves to collect runoff from the pavilion and bike rental shop, which would each undergo gutter, downspout, and drain retrofits. The stackable rain tanks use an inverted siphon system to collect rainwater at higher elevations, which would enable shallow and cost-effective roof-drain burial, project documents describe.

“Often, the key to adding green value during a conventional parking lot resurfacing project is to help the owner see the project holistically,” said Rebecca Stack, design engineer for Designgreen.“In this case, the additional costs of controlling stormwater upgrade from the lot will be recouped with a longer lasting parking surface less susceptible to water damage as this owner plans to hold the property for many years.”

The City of Lancaster Stormwater Program is now using concepts devised by the Resilient Redevelopment team to apply for grants that would allow construction to proceed.

Site-Specific Green Infrastructure Guidance

Both redesign projects — as well as most stormwater-focused retrofits — illustrate how planners must strike a balance between environmental objectives and the economic, social, and logistical needs of the specific site in order to be successful. While new parking lot designs for Joe’s Movement Emporium and Reservoir Park can serve as helpful case studies, they represent only a fraction of the many types of land use suitable for GI implementation.

To offer guidance on how GI can benefit several different types of properties, the Resilient Redevelopment team is creating an expansive site catalog that details potential approaches to stormwater management under a variety of contexts. The catalog, which includes Joe’s Movement Emporium and Reservoir Park, helps orient engineers and site owners with typical constraints and opportunities that apply to their specific type of property.

For example, apartments, condos, and other multi-family residences are likely good candidates for on-site, non-potable reuse of stormwater runoff in such applications as air conditioning and laundry. Larger buildings with durable roofs might also offer opportunities for green roofs, which can serve as an amenity to attract potential residents while reducing risks of on-site floods.

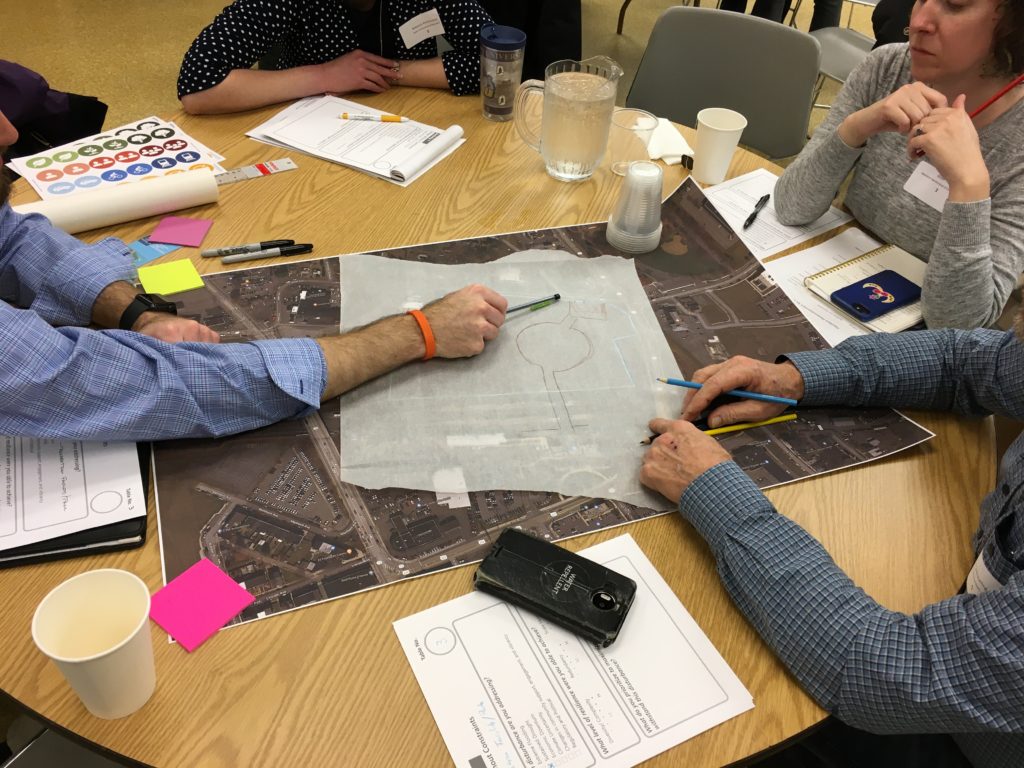

The team also held a series of site-level stormwater design workshops in December 2019, which specifically targeted the development community. The workshops, attended by engineers, landscape architects, developers, planners, government staff, and academics, challenged participants to rethink traditional approaches to stormwater management in sites with spatial or land-use constraints.

|

This project has been funded wholly or in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under assistance agreement CB96336601 to Maryland Department of Natural Resources. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor does the EPA endorse trade names or recommend the use of commercial products mentioned in this document. |