To help curb the effects of urban runoff on streambank erosion, the question municipalities must confront is whether to reduce flows or toughen channel banks. The best answer, according to Rod Lammers, lead author of a new University of Georgia (Athens) research article exploring ways to optimize erosion control, is both. The challenge is getting different agencies to work together.

“Piecemeal approaches to stormwater management and stream restoration miss synergistic benefits,” Lammers said. “They make restoration projects more prone to failure, wasting valuable resources for pollutant reduction.”

Over time, development can drastically increase the volume of runoff entering urban waterways, gradually reshape stream channels, and imperil critical infrastructure and wildlife habitats. A new research article from the University of Georgia (UGA; Athens) finds that coordinating stormwater control and stream restoration activities simultaneously best improves the resilience of urban waterways. Pexels/Pixabay

Water utilities and other municipal stormwater management agencies often prevent flows by working in highly developed areas that see the most day-to-day activity. The agencies install such controls as green infrastructure to limit the volume of runoff that reaches vulnerable waterways. Other municipal agencies work directly within waterways to stabilize channel erosion by planting new streamside vegetation and manually reshaping distorted stream banks.

The two approaches share common goals. However, agencies responsible for stormwater management and stream restoration rarely coordinate their activities due to funding or jurisdictional constraints, Lammers said. By cooperating more closely, these agencies can reduce waste while achieving greater gains for waterway resilience, Lammers’ article finds. The article, “Integrating Stormwater Management and Stream Restoration Strategies for Greater Water Quality Benefits,” was published in the August 2019 issue of the Journal of Environmental Quality.

Modeling tomorrow’s runoff with today’s data

Lammers and his team developed a specialized modeling program that details how performing stormwater management and stream restoration activities would affect channel erosion when executed independently of each other, as well as the effects of coordinating those activities. Because streambanks add more sediment and pollutants when they erode to those already reaching waterways from runoff, the researchers focused on total pollutant loads as a measure of both practices.

The team used their model to assess conditions in Big Dry Creek, a 280-km2 suburban watershed that has been severely affected by bank erosion near Denver. The model illustrated watershed-scale changes in channel elevation and width, determined the probability that a stream bank would collapse, and predicted pollutant-loading rates as far as 20 years in advance. This type of experiment would take years and incur considerable expense if attempted in the field, Lammers said.

“Computer modeling is a powerful tool. We can test the relative success of different management approaches, over years or even decades,” Lammers said. “These results can then be used by agencies to help with their planning.”

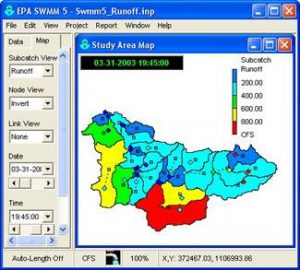

Adapted from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Storm Water Management Model, the tool visualizes site-specific data about land use, precipitation patterns, flow trajectory, and other hydrological factors at play in the region gathered from a 2010 study of Big Dry Creek’s flood hazards.

The team modeled stormwater management activities by placing hypothetical rain gardens throughout the watershed and modeled stream restoration activities by sloping different stretches of riverbank to a uniform 20 degrees. For all scenarios, the model assumed new rain gardens and more expansive sloping projects were undertaken every 5 years, simulating hourly rainfall and evaporation rates.

Stormwater control is key

According to the team’s findings, stormwater control measures improve the health of urban waterways far more than stream restoration measures. In scenarios involving stormwater management alone without any stream restoration activities, overall pollutant loads were reduced by up to 76%. Adding in stream restoration activities drove those figures by only up to 8%. Likewise, stream restoration approaches without stormwater control measures resulted in a maximum of 31% less pollution entering waterways compared to today’s figures.

The model created by Rod Lammers, UGA postdoctoral researcher, and his team is based on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Storm Water Management Model, a powerful data-visualization tool capable of simulating how runoff patterns might change in the future under various scenarios. Lammers’ model uses local data from Colorado’s Big Dry Creek watershed to examine pollutant loads 20 years in the future. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

The best results came from a “coordinated” approach, in which municipal agencies both began building green infrastructure and restoring stream reaches at the furthest point upstream within the watershed and gradually worked their way downstream. This strategy resulted in 83.2% fewer pollutants entering Big Dry Creek within the 20-year study period.

“Our results suggest that watershed-scale implementation of stormwater controls that reduce runoff volume is essential,” Lammers said. He added that deploying stormwater controls as early as possible during the urban development process pays dividends. “Much like investing early in life leads to greater financial returns, early implementation of stormwater controls and restoration can result in greater water quality and channel stability benefits.”

Lammers notes that these types of simulations have drawbacks. These include unknown relevance of the model’s findings to other watersheds, the inherent problems associated with assuming future precipitation rates, and the study’s focus on just one type of green infrastructure and stream restoration activity. However, the study provides crucial information to help municipalities make the most of their limited environmental budgets.

“Cities need to address the root cause of erosion — the altered urban water cycle,” Lammers said. “That is more effective than only treating the symptoms by stabilizing the channel itself.”

Read the article in the Journal of Environmental Quality.