Donald R. Demetrius and Camylyn Lewis with the Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services

Recognizing a repeated pattern of weather events that cause severe flooding, Virginia’s Fairfax County developed a flood response plan and implemented an Automated Flood Warning System. Engineers with Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services’ Stormwater Management Business Area worked closely with the county’s Office of Emergency Management, fire and rescue, and police in developing the response plan. County stormwater engineers developed predictive tools and established a continuous monitoring program protocol. An ongoing program of interagency training and response exercises resulted in dedicated teams ready to respond at a moment’s notice. This cycle of planning, response, and review has evolved over time, making the flood response program a living entity. Learning from this experience, county stormwater engineers have identified 11 lessons that are important to the success of any flood response program.

Lesson 1: Develop a motivating slogan

“Geronimo!”

A rallying cry helps to keep responders focused and motivated during times of crisis. The Stormwater Management Business Area (STW) developed a slogan recognizing its faith in providence while guarding against complacency and recognizing the need for preparedness. Hence the STW slogan:

Plan for the worst, hope for the best; remember that hope is not a strategy

Lesson 2: Identify susceptible communities

“You need to understand the problem before trying to solve it.”

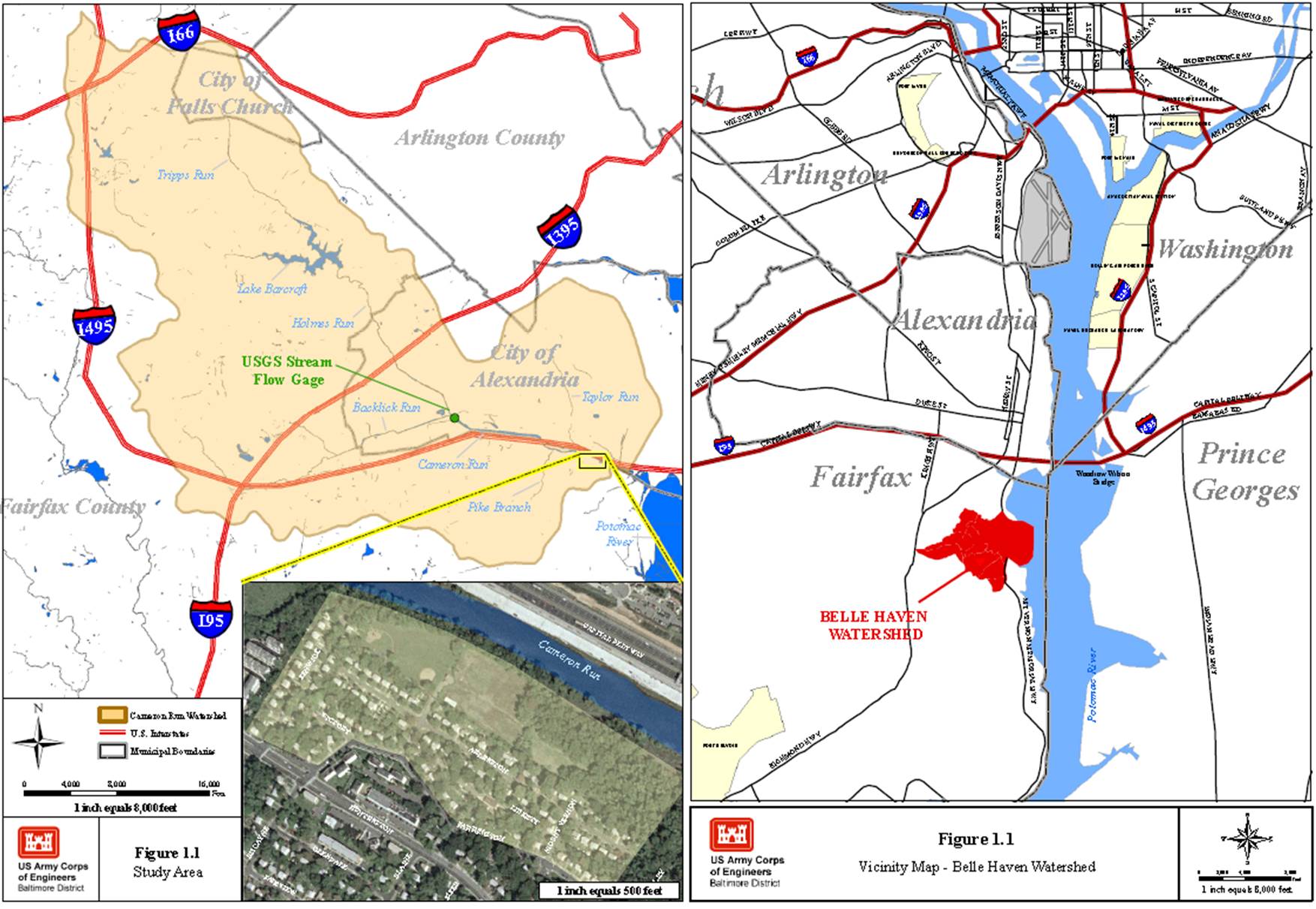

The following are two examples of communities in northern Virginia with different susceptibilities to flooding: Belle Haven and Huntington.

Belle Haven, located on the west bank of the Potomac River, has more than 500 homes and businesses. The community lies within the local Belle Haven Watershed, which drains an area of 4.66 km2 (1.80 mi2). The community’s location makes it particularly susceptible to tidal surges from the Potomac, whereas the risk of flooding from rainfall is low. A surge from Hurricane Isabel in 2003 caused the flooding of approximately 200 homes and businesses.

Huntington, with more than 200 homes, is located on the south bank of Cameron Run, which drains a watershed of 116.5 km2 (45 mi2). Historical data indicates this community is affected predominantly by riverine flooding from Cameron Run. The watershed is highly impervious, resulting in flashy flooding events that provide little warning. A June 2006 storm produced 229 to 254 mm (9 to 10 in) of rain in 48 hours, flooding more than 160 homes.

Vicinity maps of the Belle Haven and Huntington communities

Lesson 3: Develop a plan

“If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.”

From its initial conception, the county flood response plan (FRP) continues to evolve. In 2006, the county clarified agency responsibilities and developed rainfall and water surface elevation triggers along with flood risk statements expressed as codes:

• CODE YELLOW: minor flooding likely;

• CODE ORANGE: moderate flooding likely; and

• CODE RED: house flooding expected.

The county prepared communication and action plans for responding to flooding incidents. In 2008, with the completion of the FRP, responding agencies participated in a tabletop exercise.

The need for communication and teamwork among responding agencies became apparent during FRP development. Flood response requires different county agencies and organizations working together, understanding their responsibilities, and sharing information with the common goal of preventing the loss of life and minimizing property damage. Contributing to the plan was important for participating agencies so a consensus on triggers and actions could be established.

Lesson 4: Practice the plan

“Practice makes perfect, a plan works best with training.”

Regular training is essential to improving response. STW developed training requirements for staff involved in in flood response. Training on the Department of Homeland Security’s National Incident Management System (NIMS) is mandatory. Frequent training also is required to keep up with changes and improvements made to the FRP. Annually, prior to the hurricane season, STW develops response assignments for Department of Public Works and Environmental Services staff and conducts training classes for these assignments. Safety training is a core requirement for responding staff and is provided throughout the year. To ensure better communication between responding agencies, STW also provides annual field training at potential flooding sites for police, fire and rescue, and emergency management staff. Simulated events such as drills, tabletop exercises, and functional exercises also are conducted annually. These identify procedural disconnects and other areas of improvement.

A flood response training session at the Emergency Operation Center

Lesson 5: Implement an Automated Flood Warning System

“Stay alert, implement a system that never sleeps.”

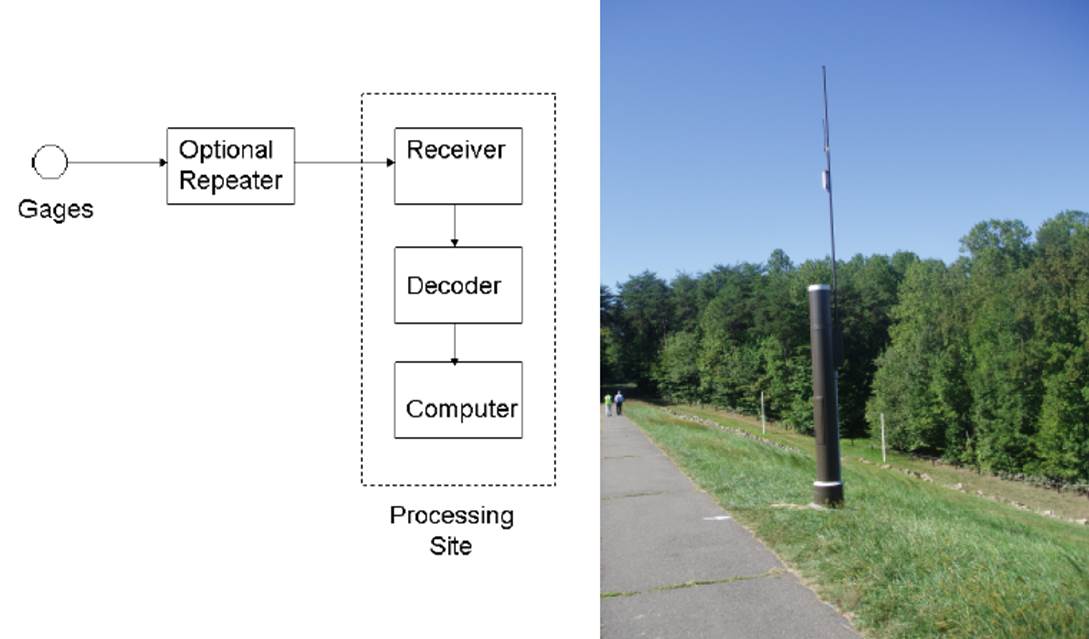

Automated Flood Warning Systems (AFWS) consist of automated event-reporting meteorological and hydrologic sensors, communications equipment, and computer software and hardware that transmit radio signals to a base station. The base station — consisting of radio receiving equipment and a computer running the AFWS software — collects the signals and processes them into meaningful information displayed on a computer screen. The system provides information on the timing and severity of flooding incidents. An AFWS increases warning times and is most valuable where flooding occurs very quickly following heavy rains.

Fairfax County utilizes a hydrometeorological network that has two components. First, National Weather Service (NWS) radar systems and a proprietary radar weather forecasting tool are used at the pre-event stage. Second, NWS, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) AFWS are used in combination with a proprietary AFWS for Fairfax County, with gauges installed at Huntington, Belle Haven, 19 dams, and other locations. The county’s proprietary AFWS has the ability to connect to NOAA tidal gauges, USGS stream gauges, and NWS rain gauges. Though the AFWS has proven to be almost indispensable to the county’s flood response efforts, it requires many man-hours of maintenance and frequent equipment checks.

A schematic and image of an Automated Flood Warning System

Lesson 6: Develop redundancies

“What can go wrong will, and at the worst time.”

In flood response, redundancy is essential and should be included in all areas of the program. A famous boxer once said, “Everyone has a plan until he gets hit the first time.” Flood response rarely runs according to plan, so there is always the need for alternatives. In a given flood event, there could be as many as 10% of the AFWS sensors down. As a result, it is prudent to have alternatives for obtaining data, which translates to manual monitoring by staff ready for deployment to the gauge location. Critical staff occasionally are unable to respond, hence the need for all positions to have backups.

Lesson 7: Develop tools to recognize flood threats

“Make the job easy; get the right tools.”

STW developed mathematical tools to recognize rainfall and tide-induced flood threats at Huntington and Belle Haven. STW engineers ran a series of hydrologic and hydraulic model simulations for both communities, with varying rainfall and tide elevations that resulted in the development of flood-depth charts. The engineers conducted topographic surveys in each community to determine the lowest point of entry to each house. They correlated data with model results and produced color coded maps indicating the combination of rainfall and tidal elevation that would cause flooding in each house. Using the simulation results, STW developed mathematical regressions that relied on tidal depths and rainfall inputs to predict flooding levels. STW engineers routinely collect real data from the county’s AFWS and use these to further refine the mathematical tools, leading to greater prediction accuracy.

Lesson 8: Determine response times

“Don’t get caught with your pants down; know how long it takes.”

There are three critical parts to response time. The first, effective lead time, is the time available for response. The second, hydrologic lead time, is the time of concentration and hydrograph travel time. Finally, the agency response time is the time taken to communicate, make decisions, deploy emergency personnel and equipment, and implement flood-mitigation action. Experience has shown that agency response time is approximately four hours for Huntington and Belle Haven.

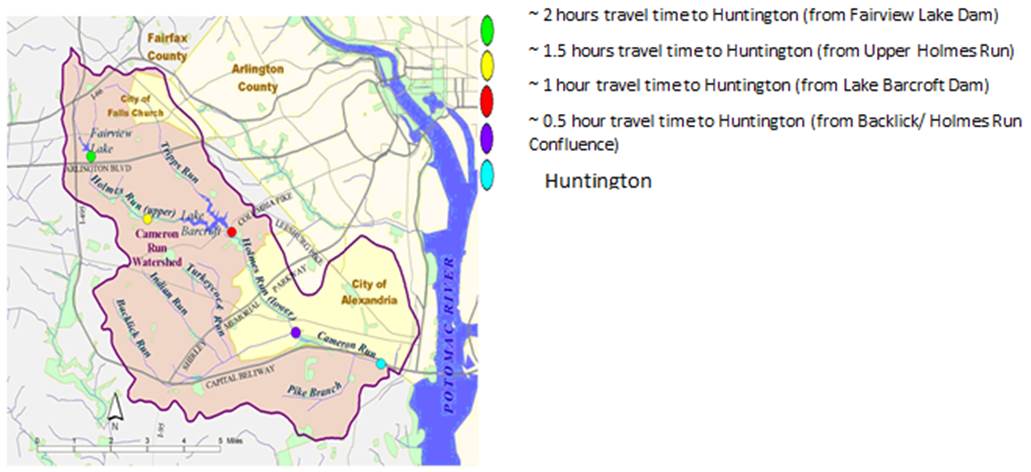

A map showing Cameron Run flood wave travel times

Effective lead time = Hydrologic lead time – Agency response time

The effective lead time can be a negative, indicating that actions should be taken before field gauges respond to the incident and may be based solely on weather forecasts.

Tide gauges along the lower Potomac River provide up to eight hours’ notice of flooding in Belle Haven, providing enough time to respond effectively. However, the most reliable stream flow gauge along Cameron Run provides Huntington with approximately 30 minutes of warning. As a result, mitigation decisions are usually based on NWS forecasts and the monitoring of proprietary and public radar systems.

Lesson 9: Organize

“Organize for an effective response.”

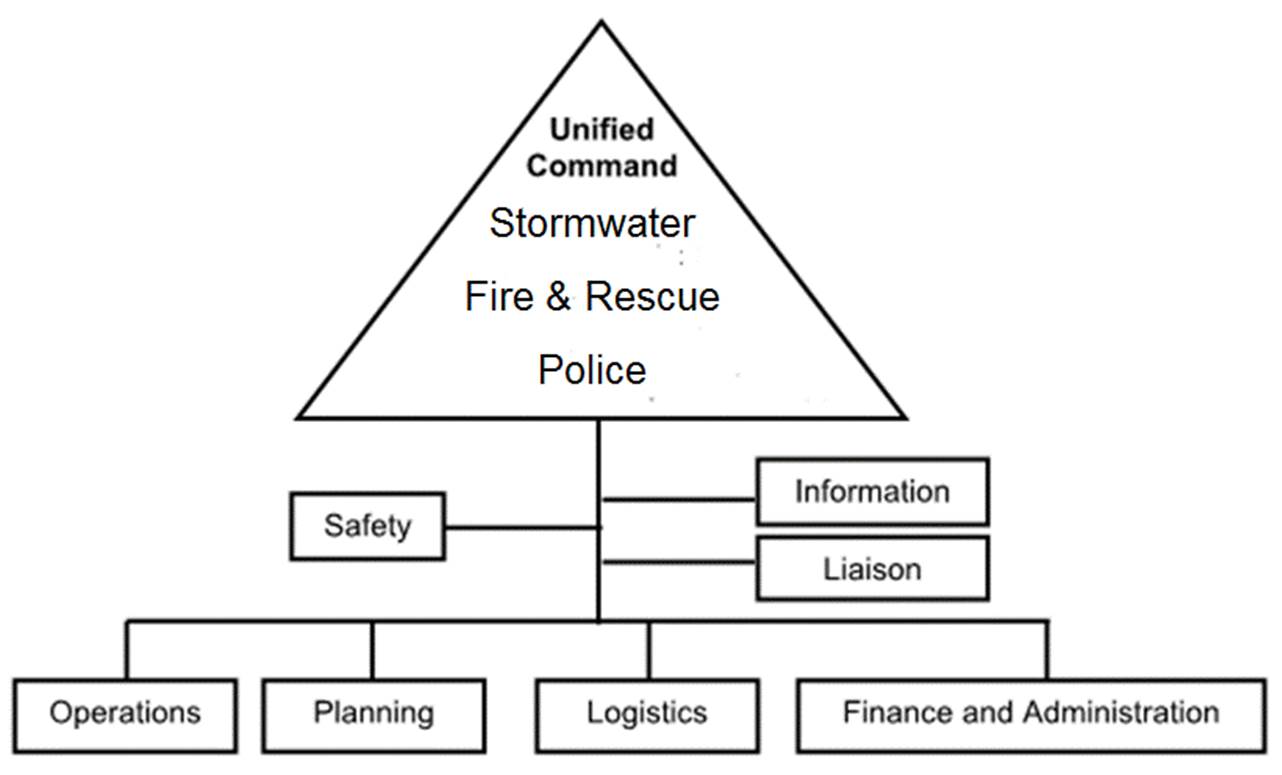

Organizing entails establishing procedures for emergency response actions, defining the responsibilities of personnel participating, and developing a framework that provides the earliest possible evaluation of flood potential. Fairfax County uses the NIMS Incident Command System. It is a standard on-scene system allowing users to adopt an integrated organizational structure matching the needs of an incident while facilitating an adequate span of control across responding entities.

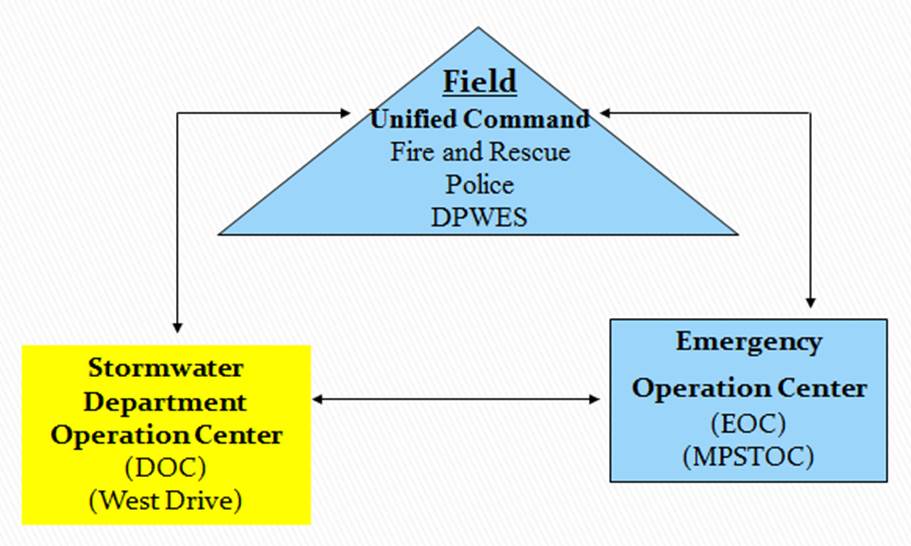

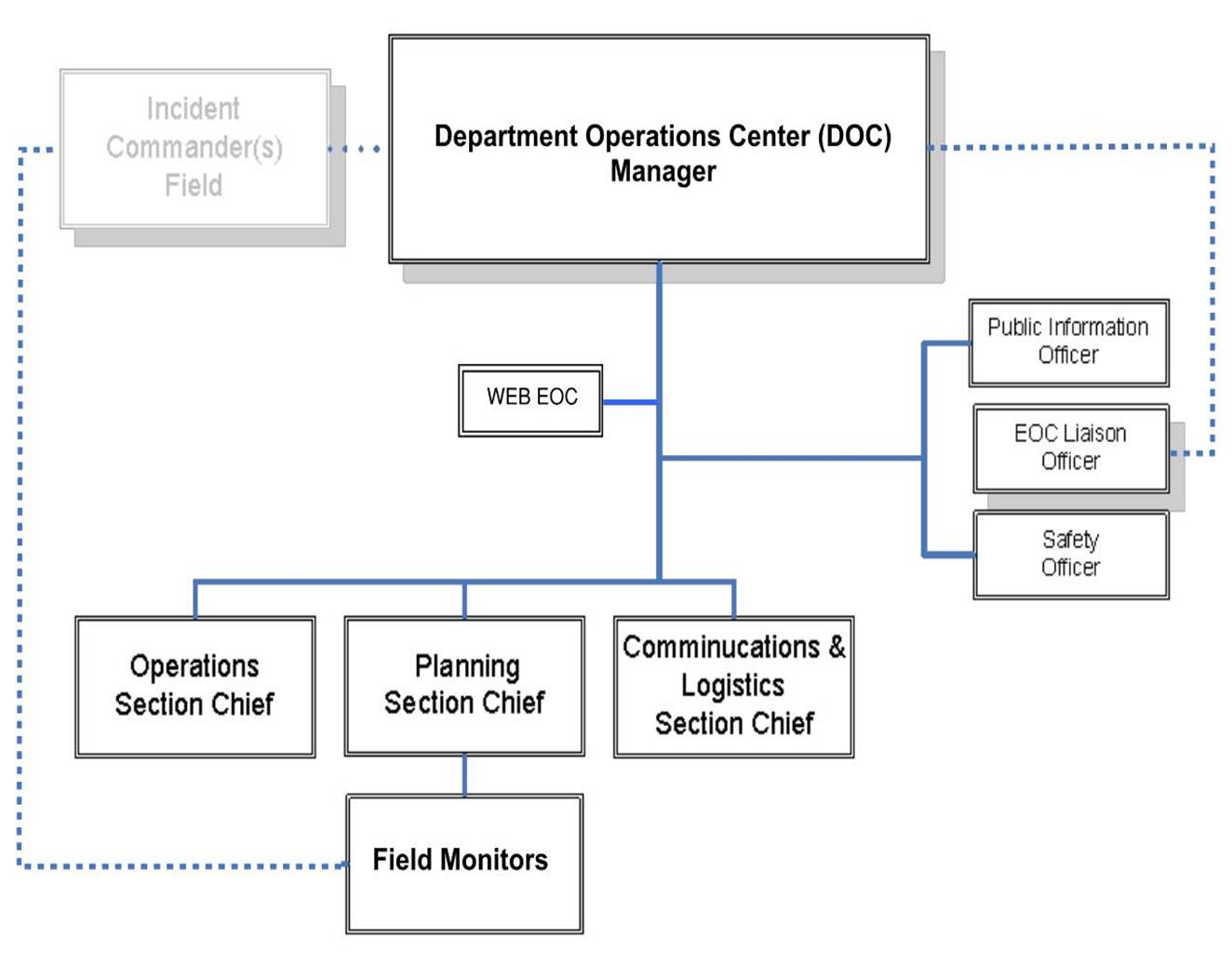

Fairfax County’s flood response is based on coordination between three responding entities: the Emergency Operation Center, the STW Department Operation Center, and the Field Unified Command. These entities are organized based on the NIMS Incident Command System structure. Each may be comprised of an incident commander with command staff including officers for public information, liaising, and safety, as well as sections for planning, logistics, and operations.

The Emergency Operation Center is where county leadership coordinates information, resources, and response and recovery actions during an emergency.

Communication and information flow between response entities

The STW Department Operation Center provides critical information and situational awareness to the field response teams by tracking storms, monitoring gauge and radar data via the AFWS, and analyzing data to determine an incident’s flooding potential. The center also provides the field with hazardous condition warnings, such as dangerous winds and tornadoes.

The stormwater Department Operations Center organizational structure

The Field Unified Command is responsible for onsite decisions, such as evacuations, and the execution of those decisions. The command team is comprised of STW, fire and rescue, and police. STW onsite staff are responsible for deciding when evacuating residents is necessary. Fire and rescue takes the lead on carrying out the evacuations, and police are responsible for security of the area during and after evacuations.

Field Unified Command organizational structure

Lesson 10: Respond

“The moment of truth; was all the preparation adequate?”

When a storm is forecasted, the Office of Emergency Management sets up teleconferences with the NWS and responding agencies. STW engineers run models and use tools to estimate the flooding risk of either CODE YELLOW, CODE ORANGE, or CODE RED. When the models predict flooding, the information is relayed to Office of Emergency Management personnel, who then send warnings to the affected community via the Community Emergency Alert Network.

Just prior to the arrival of a storm, STW and other Department of Public Works and Environmental Services staff report to the Department Operations Center. A briefing on operational objectives and safety is conducted by the center’s manager. Field and Emergency Operation Center assigned staff are then deployed, and electronic monitoring and analyzing data commences. If the threat requires evacuations, police as well as fire and rescue staff are notified, and a Unified Command is set up onsite. Once the STW field incident commander orders evacuations, fire and rescue take the lead with STW and police providing support. The evacuees are taken to shelters secured by the Emergency Operation Center. Rarely are these responses flawless, and there are always lessons learned for the next incident.

Lesson 11: Debriefing and revising the plan

“Refine and polish procedures, make time to share coffee and donuts.”

It is not until the incident is closed that staff meet to discuss what happened, what went well, and what could be improved. The timing of the debriefing is important and is best conducted within two weeks of the incident, after the staff is fully rested. The objective of the briefing is to improve response, build team spirit, and strengthen moral. Therefore, it is important to create a positive environment where all team members are comfortable sharing their thoughts and experiences. Emergency response is stressful. However, the opportunity to be part of a greater cause that prevents loss of life is immensely rewarding. Notes from the debriefing help generate an After Action Report that is used to improve the FRP and response procedures.

Donald Demetrius is chief of Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services’ Watershed Projects Evaluation Branch. He is a licensed professional engineer and has his doctorate in Civil Engineering from the University of Maryland. Demetrius is a Certified Floodplain Manager and serves as the county’s National Flood Insurance Program Floodplain Administrator. He is the prime contact for monitoring potential flood events and ensures annual training for staff involved in the county’s flood response efforts. Camylyn Lewis, civil engineer with Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services, has a Bachelor’s of Engineering from Oxford Brookes University in England. Camylyn is a licensed professional engineer and certified floodplain manager. She plays a major role in the county’s flood response efforts and was responsible for maintaining the County’s flood response plan.