Controversy has surrounded the concept of a “100-year flood” for decades among stormwater professionals. For example, these estimates often imply that a flood event with a 1% chance of occurring in a given year based on previous patterns truly will happen only once in a century, which is often inaccurate. Another issue is that they rely on various assumptions — mainly, that historical data on storm frequency and intensity can accurately inform future predictions of a region’s precipitation, a concept called stationarity.

The stakes riding on stationarity assumptions are high. Definitions for a 10-, 100-, or 1,000-year flood are a crucial consideration for stormwater professionals as they design flood-prevention infrastructure, develop local design standards and building codes, address elevation needs during roadway projects, and more. As the compounding effects of climate change increasingly refute the concept of stationarity for predicting precipitation, much of the data underpinning these efforts may no longer be as useful as they once were.

Academics and federal agencies are focusing on ways to better incorporate non-stationarity into how extreme flood events are defined, providing more actionable information to improve climate change adaptation measures.

Probing an Uncertain Future

New research from University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa) flood-prediction experts illustrates the need for updated forecasting strategies that account for the complexities of climate change. Their recent study, published in Earth’s Future, contends that even under an optimistic climate change scenario in which global carbon-dioxide emissions reach a peak by 2040 and then begin to decline, much of the world’s coastlines will experience 100-year floods as defined by present-day criteria on an annual basis by 2100. The study also suggests that by as soon as 2050, many communities could experience today’s 100-year floods every 9 to 15 years, on average.

The main factor driving these exponential increases in coastal flooding, the researchers argue, is sea-level rise. As higher seas and sinking land compound upon one another, areas farther inland will face heightened vulnerability to storm surge, increasing the likelihood that a flood will affect more densely populated areas. The team’s conclusions result from statistical methods not typically used in these types of studies, which augment historical data with forward-looking sea-level-rise projections to avoid relying on stationarity assumptions alone.

“In stationarity, we assume that the patterns we have observed in the past are going to remain unchanged in the future, but there are a lot of factors under climate change that are modulating these patterns,” said Hamed Moftakhari, study co-author and University of Alabama Civil Engineering Professor, in a statement. “We can’t assume stationarity in coastal flooding anymore.”

For their study, the researchers gathered historical data from 204 tide gauges that provided high-resolution detail on at least 55 years of annual sea-level extremes. Authors acknowledge that these gauges, which provide wide coverage for coastlines in Europe, North America, Australia, and Japan, but virtually no coverage for Africa or most of Asia, do not provide a truly global picture of future coastal-flooding threats. However, they do illustrate regional differences in how higher sea levels are likely to affect flooding. For example, while areas such as the Gulf of Mexico are likely to face more frequent and severe flooding due to land subsidence, some higher-latitude regions are predicted to experience drops in sea-level extremes as ice sheets melt and the surrounding land rises.

More than 600 million people worldwide currently live in low-lying coastal regions. Improving protections for these communities against intensified coastal flooding begins with realistic, data-backed forecasts, as well as proactive efforts to build infrastructure, develop policies, and research technologies that incorporate them, researchers say.

“Don’t forget that this is all about the level of water that we expect to experience without mitigation measures,’ Moftakhari said. “There will be technological advancements that could enhance the resilience of communities.”

Read the full study, “Coevolution of Extreme Sea Levels and Sea-Level Rise Under Global Warming,” in Earth’s Future.

Feds Invest in Forecasting

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which for 20 years has released authoritative, regional definitions for extreme events under its Atlas 14 program, also is taking steps to incorporate non-stationarity into their predictions.

Municipal planners and stormwater infrastructure designers rely on Atlas 14’s definitions of 1- to 1,000-year storm events to inform their activities. However, during the 2023 National Stormwater Policy Forum co-hosted by the Water Environment Federation (Alexandria, Virginia) and National Municipal Stormwater Alliance (Springfield, Virginia) in April, Sandra Pavlovic of NOAA’s National Weather Service Office of Water Prediction acknowledged that Atlas 14 has several procedural weaknesses that undermine its usefulness.

For one, Pavlovic explained that Atlas 14 studies are conducted by request and funded mainly by the states they concern. This has meant that updates to Atlas 14’s precipitation frequency estimates often have been inconsistent, with some states working from decades-old information. Notably, the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming never have received an Atlas 14 study, and currently rely on estimates from 1961. Additionally, Atlas 14 studies result only from historical data, and do not address how precipitation patterns are expected to shift according to climate change.

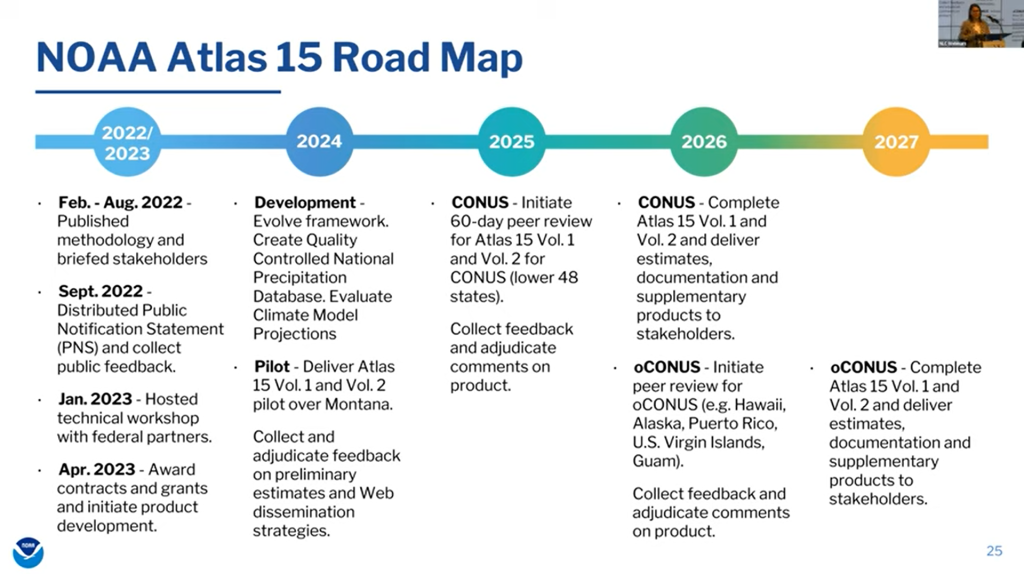

However, thanks to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) enacted in 2021, Atlas 14 is poised to evolve. For the first time, the BIL allocates direct federal funding to NOAA to update and modernize Atlas 14, as well as take steps to incorporate non-stationarity. This funding will enable NOAA to develop a new product — Atlas 15 — that encapsulates precipitation frequency information for the entire U.S. In contrast to Atlas 14, Atlas 15 will consist of two distinct volumes: One that follows the original methodology to provide up-to-date precipitation estimates based on historical data, and another that incorporates authoritative, international climate models to predict how these patterns are likely to shift in the future.

Since the BIL’s passage, NOAA has been working alongside the U.S. Federal Highway Administration as well as academia to determine a methodology that accurately incorporates non-stationarity, as well as begin the Atlas 15 development process, Pavlovic described. A single-state pilot version of Atlas 15, intended to demonstrate the methodology and gather feedback from the stormwater sector, is scheduled for release in 2024. The full release of Atlas 15 is expected by 2026 for the contiguous U.S., and by 2027 for states and territories outside the contiguous U.S.

“With NOAA’s Atlas 15 development, we are looking first to develop a pilot study over the state of Montana to share it with the public and our stakeholders and receive initial feedback not only on the science behind it, but also on our dissemination strategies — how we are presenting this information and how engineers are going to use it in their designs,” Pavlovic said.

Importantly, Pavlovic stressed that although the BIL provided initial funding to produce Atlas 15, ongoing funding will be necessary to ensure its estimates reflect the latest science. Legislative movement already is under way to meet this need, but uncertainty remains.

“Thankfully, with the FLOODS Act that passed last December, there is language that authorizes NOAA to establish a program that will be responsible for compiling, estimating, analyzing, and communicating precipitation frequency information in the United States and updating these standards no less frequently than once every 10 years,” Pavlovic said. “However, while the language exists, the appropriation has not been made yet — that would be a very good step for the future of this program.”

Top image courtesy of Olya Adamovich/Pixabay

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.