Each summer, the North American Monsoon system brings a spate of intense storms across the central and southwestern U.S., which often last days or even weeks before dissipating as they move east. However, they are notoriously unpredictable; while these seasonal storms are an important boon to agriculture and water supplies, they also can cause disastrous flash flooding.

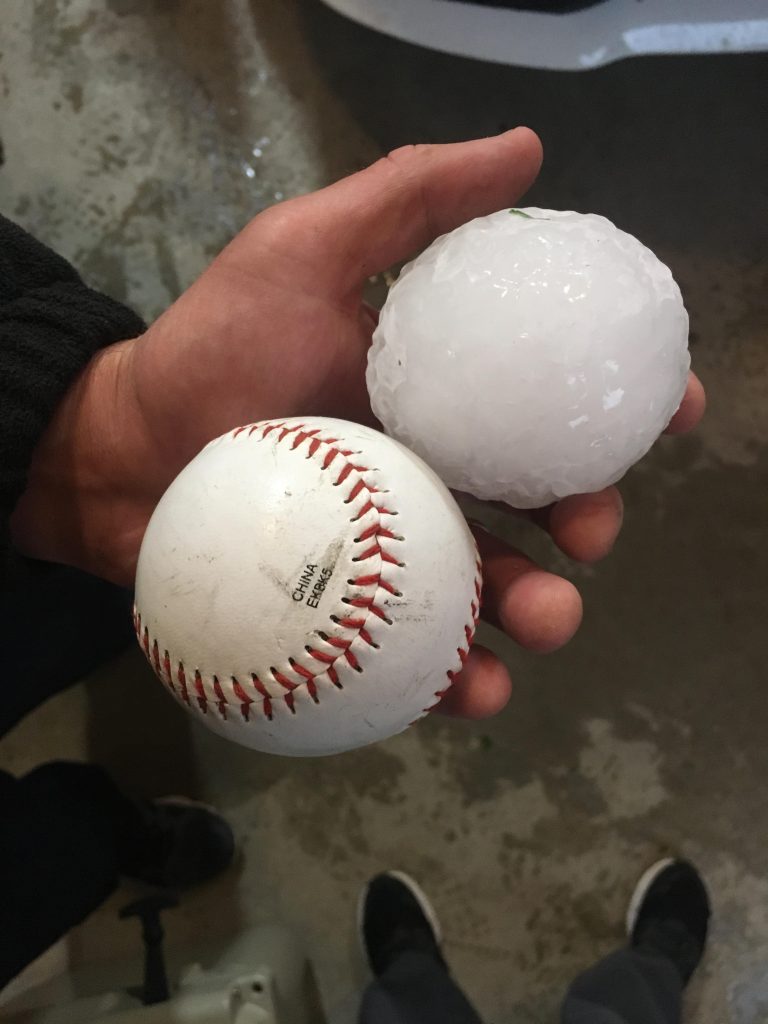

For example, the 2018 monsoon generated a series of severe convective storms across Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and South Dakota. In addition to baseball-sized hail and winds as high as 90 miles per hour, the storms brought record-breaking rainfall volumes, which combined to incur millions in property damages .

Researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL; Richland, Washington) have discovered that a phenomenon occurring simultaneously hundreds of miles away — a series of historically destructive wildfires in California and Oregon — likely contributed to the 2018 monsoon’s severity. By increasing temperatures and generating plumes of smoke across an enormous area, the researchers contend, the wildfires affected weather patterns on an unprecedented scale.

“The more we understand about the contributing factors behind storms like this, which cause massive property loss, the better we’ll be able to prepare for them,” said Jiwen Fan, PNNL earth scientist and co-author of a new study about the discovery in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in a release. “And, as we look at the future climate, we know wildfires will increase, particularly in the west.”

The 2018 Anomaly

When a major storm broke out above the central U.S. on July 26, 2018, three severe wildfires — California’s Carr and Cranston Fires and Oregon’s Long Hollow Fire — already were raging. As the fires continued to scour acres of land over the following weeks, consecutive storms of similar intensity would occur in the central U.S. each day through July 29.

This timing, in itself, was an anomaly, PNNL researchers describe. A period where West Coast wildfires and central U.S. monsoons overlapped for more than three consecutive days had not been observed in at least 20 years, the authors write. When those summer storms turned out far more severe than any in recent history, Fan and her team began investigating whether a link existed between the historic wildfires and the historic storms.

“I thought, maybe there’s some kind of connection there,” Fan said.

Using a sophisticated weather systems model developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (Boulder, Colorado), the team carried out high-resolution simulations to explore how abnormalities resulting from the wildfires might affect broader weather systems, including the North American Monsoon.

The model detailed that the 2018 wildfires increased air temperatures in their immediate vicinities by as much as 40 times the resting average for July. This additional heat caused local air pressure to skyrocket. As wind from the West Coast already tends to move east, this ultra-pressurized air traveled to the low-pressure monsoon system forming above the central U.S. at a higher-than-usual speed — bringing with it high concentrations of aerosolized particles generated by massive plumes of smoke.

When the warm West Coast air mingled with the budding storm clouds above the central U.S., the influx of aerosolized particles provided extra surface area onto which water vapor in the clouds could attach and condense into precipitation. The added heat also provided more energy — and thus, more mobility — for this water vapor, which ascended to greater (and colder) atmospheric heights and fell further after they condensed. This increased movement, the model found, generated large hailstones large enough to cause damage even despite their occurrence in the middle of summer.

“The cost of the storms we studied exceeded $100 million in damage,” said Yuwei Zhang, PNNL atmospheric scientist and first author of the study, in a release. “If we know that distant wildfires contribute to stronger storms, that information could bring about better projections, which might help avoid some degree of destruction.”

More Common With Climate Change

According to the study, influence from the West Coast wildfires was directly responsible for a 19% increase in total rainfall to affect the central U.S. between July 26 and 29. The study also suggests that the wildfires significantly enhanced the occurrence of intense precipitation capable of causing flash flooding — falling at more than 10 mm per hour — while discouraging less severe rainfall. Air-pressure differentials were found to increase maximum updraft speeds in the storm system by about 30%.

The researchers acknowledge that their findings may only be applicable to a small subset of weather phenomena, when larger-than-average wildfires and storms occur simultaneously within a relatively restrained distance of each other. However, evidence from the last few years suggests that climate change is causing wildfire season in the western U.S. to begin earlier in the summer, placing its onset increasingly within the range where it would overlap with the North American Monsoon.

“Severe storms in the central U.S. are also projected to increase,” Fan said. “Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that these co-occurring events would happen more frequently, and the impact of western wildfires on central storms may become increasingly important in the future.”

Read the full, open-access study, “Notable impact of wildfires in the western United States on weather hazards in the central United States,” in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Top image courtesy of Dave Ritchey/U.S. National Weather Service

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.