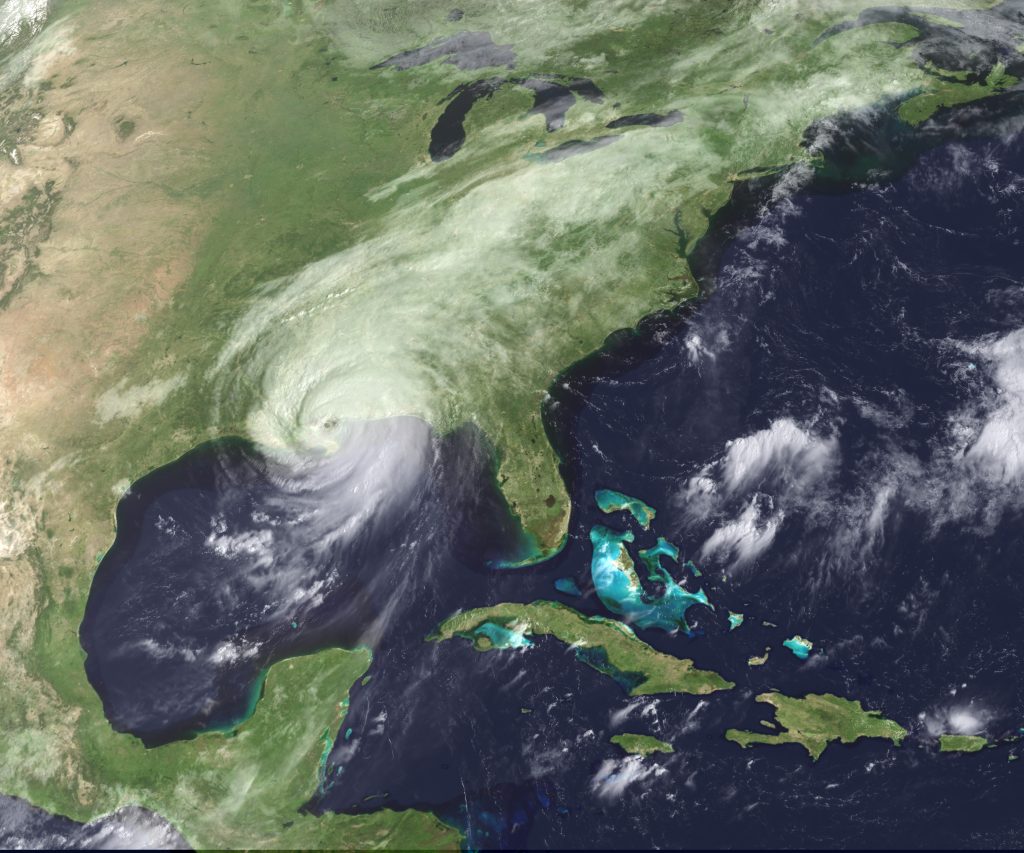

The looming threat of natural disasters — such as hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes — demands that large cities develop detailed plans to help their residents evacuate during a worst-case scenario. Making these plans both actionable and realistic, however, requires emergency management personnel to consider the needs of those without access to their own vehicles in addition to simply recommending the safest routes out of the city for motorists.

This necessity was perhaps never clearer than during Hurricane Katrina, which hit New Orleans in August 2005. Although the city had developed basic plans to evacuate those without access to vehicles before the storm arrived, the realities of evacuating nearly 500,000 people at once caused those plans to break down quickly, stranding thousands of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

Nearly two decades after Katrina, new research from Florida Atlantic University (FAU; Boca Raton) finds that most major U.S. cities still do not maintain robust evacuation plans that consider the needs of the carless and the movement impaired. The study, which examined natural disaster protocols in the 50 largest U.S. cities, was recently published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction.

“While it is promising that more cities are developing evacuation plans,” said John L. Renne, senior author of the new study and director of FAU’s Center for Urban and Environmental Solutions, in a release, “it remains disheartening that not every city was able to learn the lessons of not being prepared, especially for carless and vulnerable populations, as showcased to the nation during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.”

What Went Wrong During Katrina

In the weeks following Hurricane Katrina, which caused nearly 2,000 fatalities and approximately USD $163 billion in damages (adjusted for inflation), emergency management professionals conducted a deep dive into the factors that led the storm to become one of the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history.

Speaking to NPR one month after Katrina, then-New Orleans City Councilwoman Cynthia Hedge-Morrell described that the city had maintained a plan for evacuating its carless population — a network of temporary bus stops throughout the city, where municipal vehicles would collect residents and head two hours north via a major highway. However, despite restricting highway traffic into the city and designating all lanes as exclusively outward-bound, the constant flow of evacuating motorists choked highway traffic to a standstill in the days before Katrina hit.

Recognizing that adding city buses to this traffic would not only exacerbate the issue but potentially endanger passengers, the city’s Office of Emergency Preparedness made a last-minute decision to instead bus thousands of carless residents to the New Orleans Superdome, considered a “shelter of last resort” to endure the brunt of the storm. The new plan would send evacuees north to more permanent shelters after the storm had passed — but when levees broke, buses flooded, and roads were rendered impassable, these residents were stranded indefinitely.

Evacuating seniors represented another challenge, Joe Donchess, then-Director of the Louisiana Nursing Home Association, told NPR. Without specific guidance from the city for nursing homes, the decision of whether — and how — to evacuate nursing-home residents was largely left up to each individual facility. Only 15 out of nearly 50 New Orleans nursing homes evacuated before the storm, with the remainder opting to shelter in place. As a result, these vulnerable residents were trapped without food, water, or electricity for several days, causing more than 100 deaths.

The city’s experience offered a cautionary tale for emergency managers, write authors of the FAU study: Effective evacuation plans must consider all segments of a city’s population, including, crucially, those without the means to evacuate by themselves.

Seven Cities Top Preparedness List

Reviewing evacuation plans either publicly available online or gathered from interviews with municipal emergency managers, the researchers concluded that most major U.S. cities do not have specific provisions for evacuating their carless residents.

Their analysis sought to develop a standardized rating system to benchmark the robustness of evacuation plans, applicable across contexts and geographies, based on five criteria. They included whether cities maintained a registry of residents requiring special needs in the event of an evacuation; whether specific transportation accommodations were in place for these individuals; the geographic extent of public pick-up locations; the number of transportation options provided to evacuate carless individuals; and provisions to evacuate pedestrians. Based on these factors, researchers assigned each city a score on a 1-10 scale ranking the strength of their evacuation plans.

The study also explored how these plans evolved in the years since Hurricane Katrina, comparing each city’s guidance in 2005 against that of the mid-2010s. New Orleans, for example, learned from Hurricane Katrina, now maintaining one of the country’s most robust evacuation plans, according to the study.

Only seven out of 50 cities — Charlotte, Cleveland, Jacksonville, Miami, New Orleans, New York, and Philadelphia — ranked within the 8-10 range.

“Many cities that have strong plans are coastal cities that have experienced strong hurricanes in the past,” Renne said. “This study lends support to the theory that cities do not develop strong evacuation plans, ones that accommodate the needs of all people, unless they have already experienced a major disaster or are under a threat.”

In the study, 20 cities achieved a moderate ranking, with six cities earning a “weak” score between 0 and 4. According to the study, 17 cities — including such major metropolises as Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Las Vegas — either did not have publicly available evacuation plans for carless and vulnerable residents, or emergency managers declined to provide them. This is especially concerning, the researchers write, as the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency urges cities to make evacuation plans publicly available before a disaster occurs so citizens can prepare accordingly.

“In answer to the question we posed in our paper, ‘what has America learned since Hurricane Katrina?’ — the answer based on our findings is clearly: not enough,” Renne said.

Explore detailed findings from the study, “What Has America Learned Since Hurricane Katrina? Evaluating Evacuation Plans For Carless And Vulnerable Populations In 50 Large Cities Across The United States,” in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction.

Top image courtesy of David Mark/Pixabay

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.