According to new research, rainfall virtually everywhere on Earth contains levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that exceed safety limits set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other environmental regulators, affecting even the world’s most remote regions. The finding confirms that atmospheric deposition via precipitation is one of many routes by which PFAS contamination spreads throughout long distances and an array of environments, including air, soil, and surface water. It also underscores the health risks of consuming untreated rainwater — a vital source of drinking water in many arid and tropical regions of the world.

Authors behind the new study, representing Stockholm University (Sweden) and ETH Zurich (Switzerland), suggest that PFAS contamination represents a previously unrecognized “planetary boundary” — a global, quantitative threshold which compromises humanity’s rate of development if surpassed.

“Due to the global spread of PFAS, environmental media everywhere will exceed environmental quality guidelines designed to protect human health and we can do very little to reduce the PFAS contamination,” said Martin Scheringer, study co-author and ETH Zurich environmental chemist, in a release. “In other words, it makes sense to define a planetary boundary specifically for PFAS and, as we conclude in the paper, this boundary has now been exceeded.”

Contamination Outpaces Regulation

The research team compiled findings from several studies published since 2010 that examined the occurrence of four of the most common PFAS — perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) — in rainfall, covering both urban and rural environments as well as Antarctica and the Tibetan Plateau, among Earth’s most remote biomes. They then compared these PFAS levels with advisory contaminant limits for drinking water specified by EPA, the Dutch and Danish governments, as well as the European Union.

Each of these limits has grown increasingly stringent in recent years as the body of research about PFAS exposure risks expands. In June, for example, EPA lowered advisory limits for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water from 70 ng/L for the sum of both substances to 20 pg/L and 4 pg/L respectively. Last year, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency announced that drinking water must not contain more than a total of 2 ng/L of PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and PFNA.

“There has been an astounding decline in guideline values for PFAS in drinking water in the last 20 years,” said Stockholm University environmental scientist Ian Cousins, lead author of the study, in a release. “For example, the drinking water guideline value for one well-known substance in the PFAS class, namely the cancer-causing PFOA, has declined by 37.5 million times in the U.S. Based on the latest U.S. guidelines for PFOA in drinking water, rainwater everywhere would be judged unsafe to drink.”

The team’s review found that the levels of PFOA detected in rainfall by all studies in all regions far exceeded EPA’s advisory limits. The lowest recorded concentration of PFOA was in the Tibetan Plateau, with a median contamination level of 55 pg/L — approximately 14 times higher than EPA guidelines. PFOS, too, exceeded limits set by EPA, the Environmental Quality Standard for Inland European Union Surface Water, and other measures, in all but two studies conducted in Antarctica and the Tibetan Plateau.

A Threat to Human Development

Originally prized by industry for their durability and longevity, as an environmental pollutant, PFAS have proven especially persistent in the hydrosphere. After discharge from industrial facilities, PFAS eventually reach waterways and oceans, where instead of dissolving, they commonly enter the atmosphere via sea-spray aerosols. Rainfall, in turn, returns the chemicals to the surface, perpetuating their environmental threats even decades after their initial release. Although the world’s largest PFAS manufacturers had phased out their use by the early 2000s, the chemicals continue to accumulate even within the most remote corners of the world.

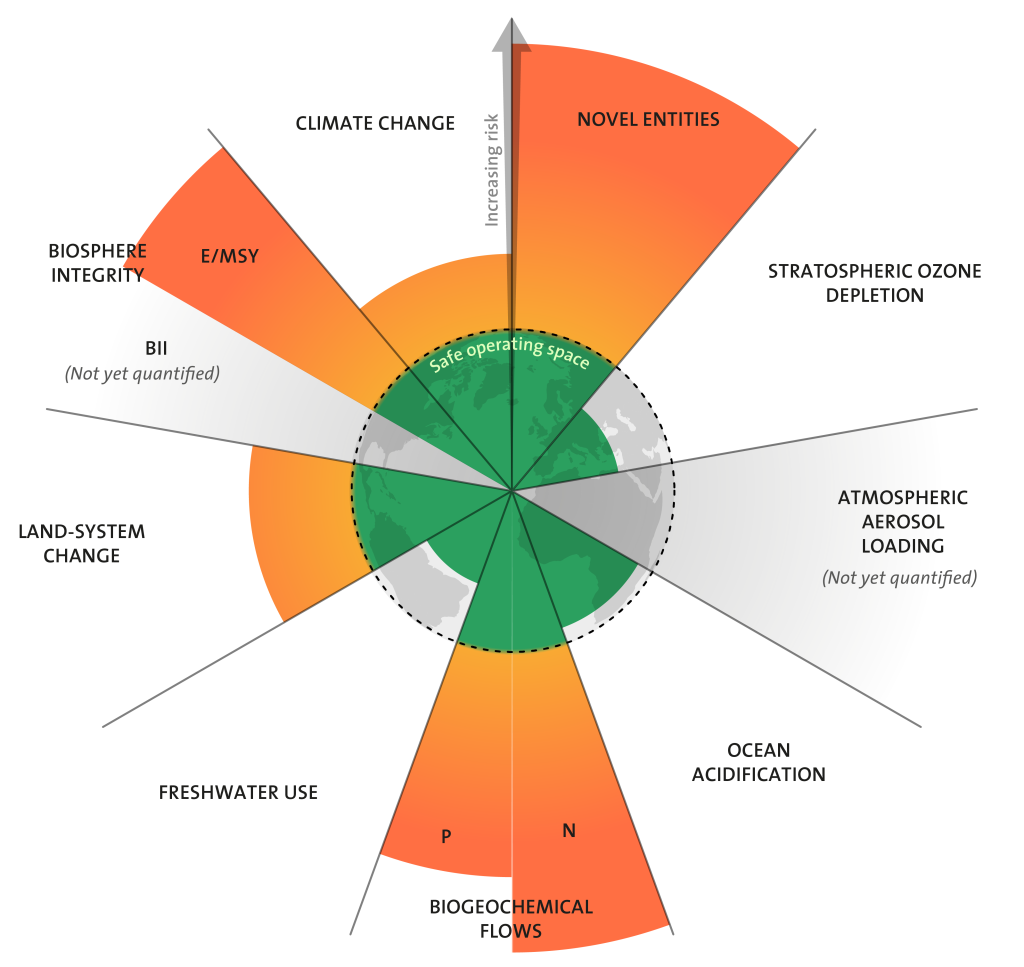

Because of the ubiquity of PFAS contamination in rainfall, soil, and surface water and the inability to reverse this contamination on a global scale with existing technology, the researchers argue that conservationists should regard PFAS as a tenth planetary boundary.

The concept of planetary boundaries was first proposed in 2009 by a group of 28 scientists coordinated by the Stockholm University Resilience Centre. They include nine measurable processes, such as stratospheric ozone depletion, ocean acidification, biosphere integrity, and climate change, each underlined by a series of metrics and indicators. Among these metrics are a threshold for each boundary, which if surpassed signal the threat has become irreversible using existing tactics. To varying degrees, several of these thresholds have already been exceeded, including climate change, land-use change, and nutrient pollution.

Read the full, open-access study, “Outside the Safe Operating Space of a New Planetary Boundary for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS),” in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Top image courtesy of Roman Grac/Pixabay

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.