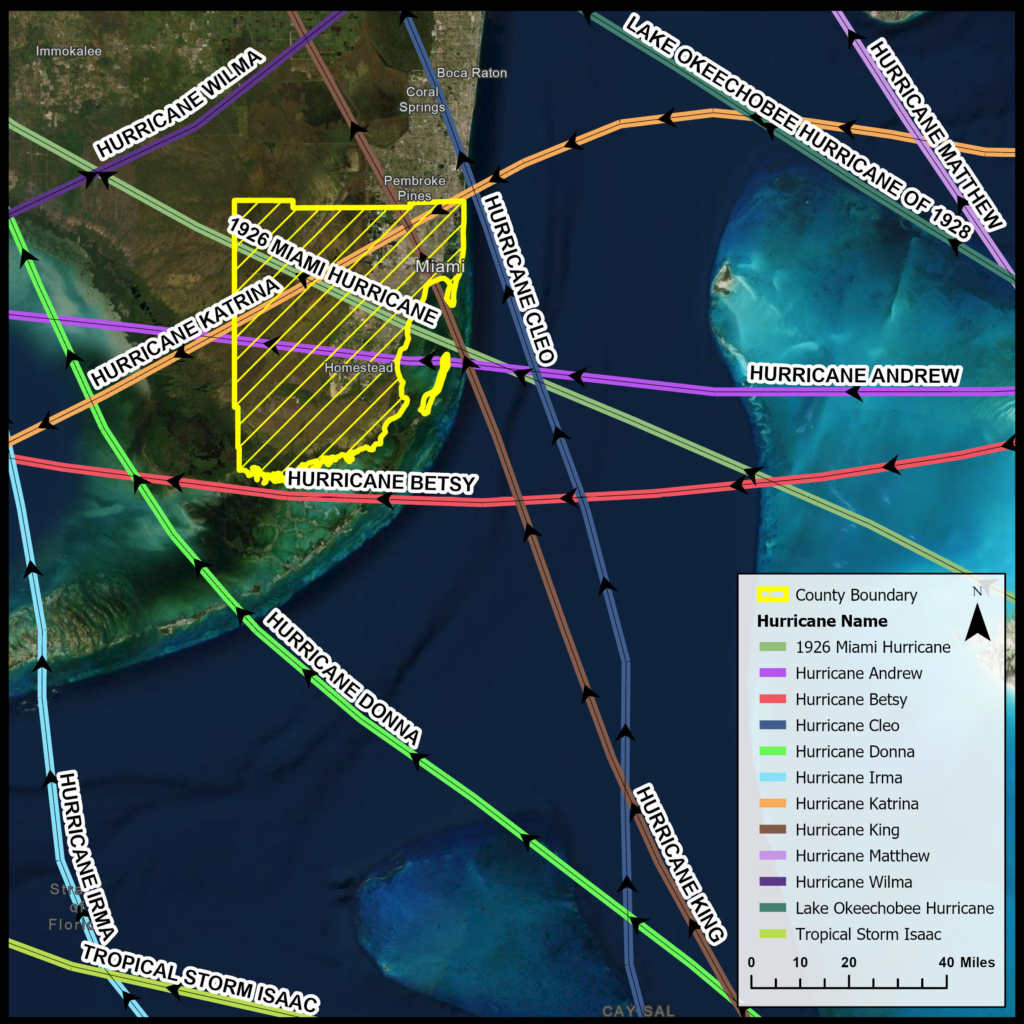

The “Great Miami Hurricane” struck South Florida in 1926, creating intense wind gusts as fast as 240 km/h (150 mph). High winds carried huge volumes of rain and ocean water inland, leading to water levels as high as 4 m (12 ft) in downtown Miami. The historic storm caused nearly 250 deaths and more than $164 billion in damages, adjusted for inflation.

While South Florida has not experienced storm surge on the scale of the Great Miami Hurricane in several decades, coastal flooding from storm surge is a perennial issue for the low-lying region, which experiences a growing average of about nine hurricanes per year according to the Insurance Information Institute (New York).

To protect Florida’s largest population center, a crucial international trade hub, and habitats for countless rare and endangered wildlife species, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) is in the early stages of a nearly $4.6 billion plan aimed at improving safeguards against storm surge in Miami-Dade County. In June, U.S. ACE released a 443-page feasibility report outlining the plan.

“This is not a new topic for this region,” said U.S. ACE Norfolk (Va.) District Commander Patrick Kinsman in a video introducing the project. “Coastal storms are a reality of coastal living, and the risks continue to increase over time with rising sea levels and changing weather patterns.”

An Array of New Resilience Measures

U.S. ACE worked alongside other federal agencies, such as the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), as well as the Miami-Dade County government to devise the report’s recommendations. The study stresses its narrow focus on storm surge, emphasizing that several other federal, state, and local programs are addressing other facets of coastal-storm resilience in the region.

“This Miami-Dade study has the goal of reducing risk to the Miami-Dade area from future coastal storm events and especially storm surge, specifically to reduce the economic damage as well as threats to life and safety,” Kinsman said.

Focusing on seven areas of the county that face the highest storm-surge risks combined with the densest populations, the latest iteration of the report calls for an array of infrastructure-based interventions. These mainly include new floodgates, floodwalls, and pump stations built in strategic locations.

The plan also recommends non-structural resilience strategies, such as elevating residential structures above anticipated flood height, restoring underwater vegetation that can mitigate storm surge effects in Biscayne Bay, and creating “dredged material spoil islands,” which use material resulting from the construction of navigation channels to provide new wildlife habitats.

Among other interventions, major recommendations specified in the study include:

- subsidizing costs of elevating about 2,300 flood-prone buildings;

- implementing enhanced flood-proofing upgrades on an additional 3,850 properties; and

- building a floodwall spanning about 1.6 km (1 mi) in length with a width of approximately 15 m (50 ft).

Balancing Benefits and Burdens

Recommendations identified in the report underscore a primary focus on conventional “grey” infrastructure, such as concrete floodwalls and metal pump stations.

As described in the report, while this type of infrastructure is considered cost-effective, it may also entail negative environmental and social effects. While assessing the plan’s potential environmental impacts, authors considered factors such as habitat coverage, cultural and recreational value, air and water quality, and more. The report outlines that building new seawalls likely would result in permanent losses of submerged aquatic vegetation, coral reefs, and mangroves. The project’s largest proposed floodwall would also obstruct views from Miami to the Biscayne Bay, creating adverse effects for tourism and recreation.

Although the plan does include various nature-based recommendations, such as strategically planting native vegetation and restoring degraded habitats for rare birds, public comments received thus far indicate support for green infrastructure to play a larger role.

“Almost every individual who showed up to make a public comment about this study was almost begging for green infrastructure,” Rachel Silverstein, executive director of nonprofit group Miami Waterkeeper, told WLRN Public Radio and Television in June. “Things like restoring coral reefs, building mangroves, dune ecosystems, wetland restoration, and all of those things both provide an environment benefit, but have also been shown to be really potent storm surge protection features.”

U.S. ACE is seeking public comments on its plan until August 19, 2020. After revisions, the agency plans to send the report to U.S. Congress by September 2021. If approved by U.S. Congress, plans would be completed by 2030, the report describes.

Read the full report and make comments at the U.S. ACE website.