In urban environments, humans pave over landscapes that would otherwise absorb stormwater. However, it turns out humans are not the only species that disrupts natural hydrological processes as their habitats develop.

By cutting trees, digging canals, and building dams, beaver colonies shape their forest dwellings in ways that transform flooding patterns, the local food chain, and the structure and size of nearby waterways. But these effects, in the long run, often are beneficial for stormwater management and water quality. The flooding results in huge swaths of new wetland habitat over many years.

A new study from University of Eastern Finland (Joensuu) and University of Helsinki (Finland) researchers, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, explores these long-term shifts over nearly 50 years.

“The spread of the beaver in our study area has created a diverse and constantly changing mosaic of beaver ponds and beaver meadows of different ages,” said lead study author Sonja Kivinen, a University of Eastern Finland environmental geographer, in a release. “Beavers can help to restore wetland ecosystems and entire boreal forests, and they also help in conserving the biodiversity of these environments.”

Nature’s Stormwater Professionals

In a 136-km2 (53-mi2) boreal forest near Evo in southern Finland, findings from numerous other ecological studies as well as the work of a local game research station have provided ample data about local beaver activity since 1970. The researchers focused on this forest, which is home to at least nine large beaver colonies. They investigated the changing relationship between beavers and their environment through 2018.

Forests across Europe once featured dense concentrations of European beavers before the fur trade brought the species to extinction in the 19th century. The American beaver, which the researchers note creates similar types of dams, was introduced to southern Finland in 1957. In the Evo forest, the distribution of American beavers today approaches that of the European beaver in the early 1800s, the study describes.

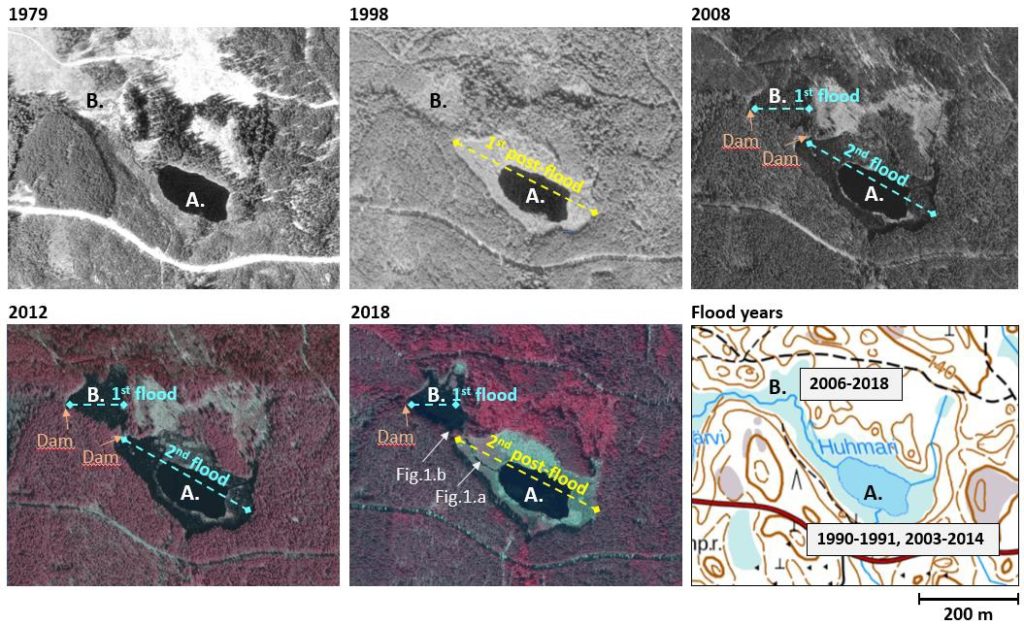

The research team processed available data about beaver distribution and flooding locations using spatial analysis software. Beginning their analysis in 1970, the researchers identified areas where beaver activity was most likely to be the main cause of flood events, estimating the duration of those effects and how they shaped the local landscape. When possible, the team also incorporated aerial images of the study area to facilitate comparisons between historical conditions and the forest’s current topography.

Sustained Flooding Benefits Biodiversity

In 1970, just over a decade after the beavers’ reintroduction to Evo, the region contained only six sites that became prone to flooding as a result of beaver activity. By 2018, that number had jumped to 69 sites, with an average of 13 new flood sites per decade, the researchers estimate. As the beaver population dispersed throughout the forest, many of these sites became interconnected, effectively creating new wetland habitats.

Researchers emphasized the long duration of many flood events captured in the data, which gradually transform the environments they affect. According to their results, the average duration of a beaver-related flood event was approximately 3 years, with a handful of exceptional sites remaining flood-prone for several decades. 90% of all detected floods lasted for at least one year.

Studying the presence of other types of wildlife in areas affected by beavers revealed positive, long-term effects on biodiversity. Many of the “habitat patches” represented in the study saw steadily increasing numbers of fish and water-dwelling birds, for example, and trees felled by beavers created new opportunities for insects and small mammals.

“Thanks to beaver activity, there is a unique richness of wetlands in the forest landscape,” said study co-author Petro Nummi, a wetland ecologist at the University of Helsinki. “Flowages dominated by bushes, beaver meadows, and deadwood that can be used by various other species.”

Read the full, open-access study, “Beaver-induced spatiotemporal patch dynamics affect landscape-level environmental heterogeneity,” in Environmental Research Letters.