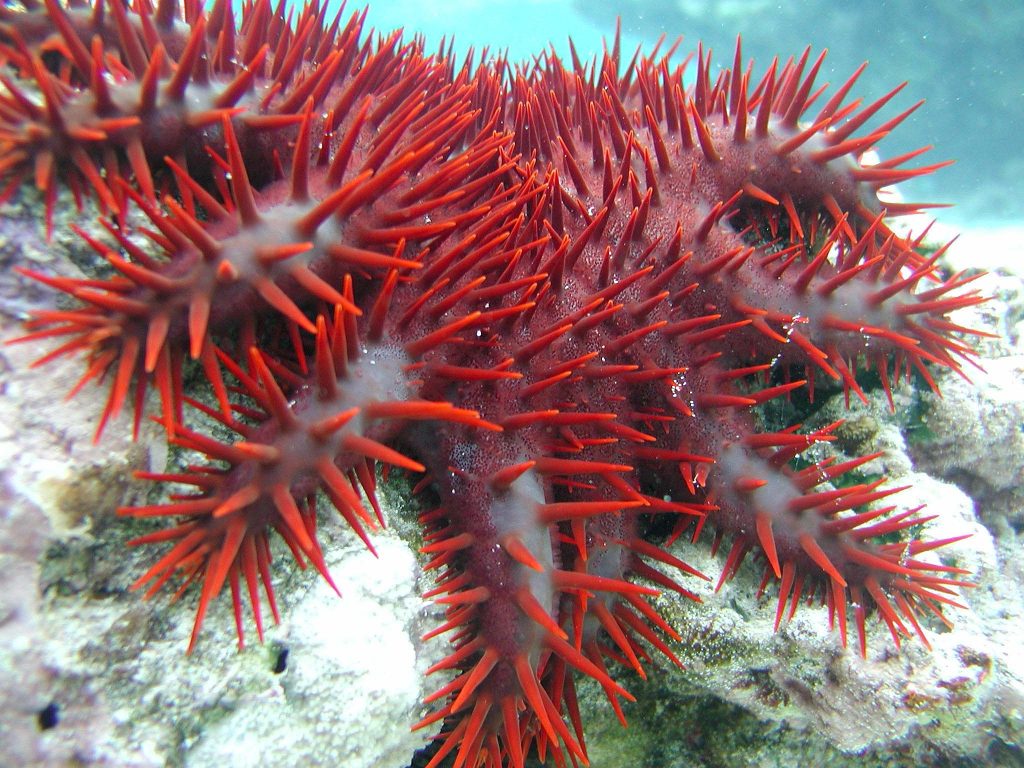

One of the greatest threats to the health of the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral system spanning more than 337,000 km2 (130,000 mi2), is the appetite of a reef-eating starfish measuring roughly 30 cm (12 in.) in length.

Although the crown-of-thorns starfish is native to the Great Barrier Reef, it responds similarly to algae in the presence of such nutrients as nitrogen and phosphorus. When more nutrients enter the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem than natural, for example as a result of stormwater runoff carrying agricultural fertilizers into the ocean, crown-of-thorns starfish numbers surge. According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (Queensland, Australia), these human-caused starfish outbreaks can lead to loss of coral coverage on a scale comparable to cyclones and major chemical spills.

Inland from the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, one of the world’s largest sugarcane industries adds approximately AUD $2 billion to the Australian economy each year, estimates the Queensland Farmers’ Federation (Brisbane). Sugarcane growers in Queensland might be aware that their fertilizer practices have a direct effect on the Great Barrier Reef, but until now, farmers had no way to quantify their specific contributions to nutrient pollution or gauge whether modifying their practices could make a difference.

Providing this information to farmers in an easily understandable and user-friendly way was the inspiration behind 1622WQ, a new app for Queensland farmers developed by agricultural scientists with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), said lead app developer Peter Thorburn.

“Sugarcane growers told us they wanted quick and easy access to water quality information, so they could find out what’s going on with their crops and make better decisions,” Thorburn said in a statement. “Sugarcane is the first farming system we’ve looked at, but we could deploy [the app] in any area where real-time water quality data could help inform agricultural practices.”

Advanced Technology at a Simple Point-of-Use

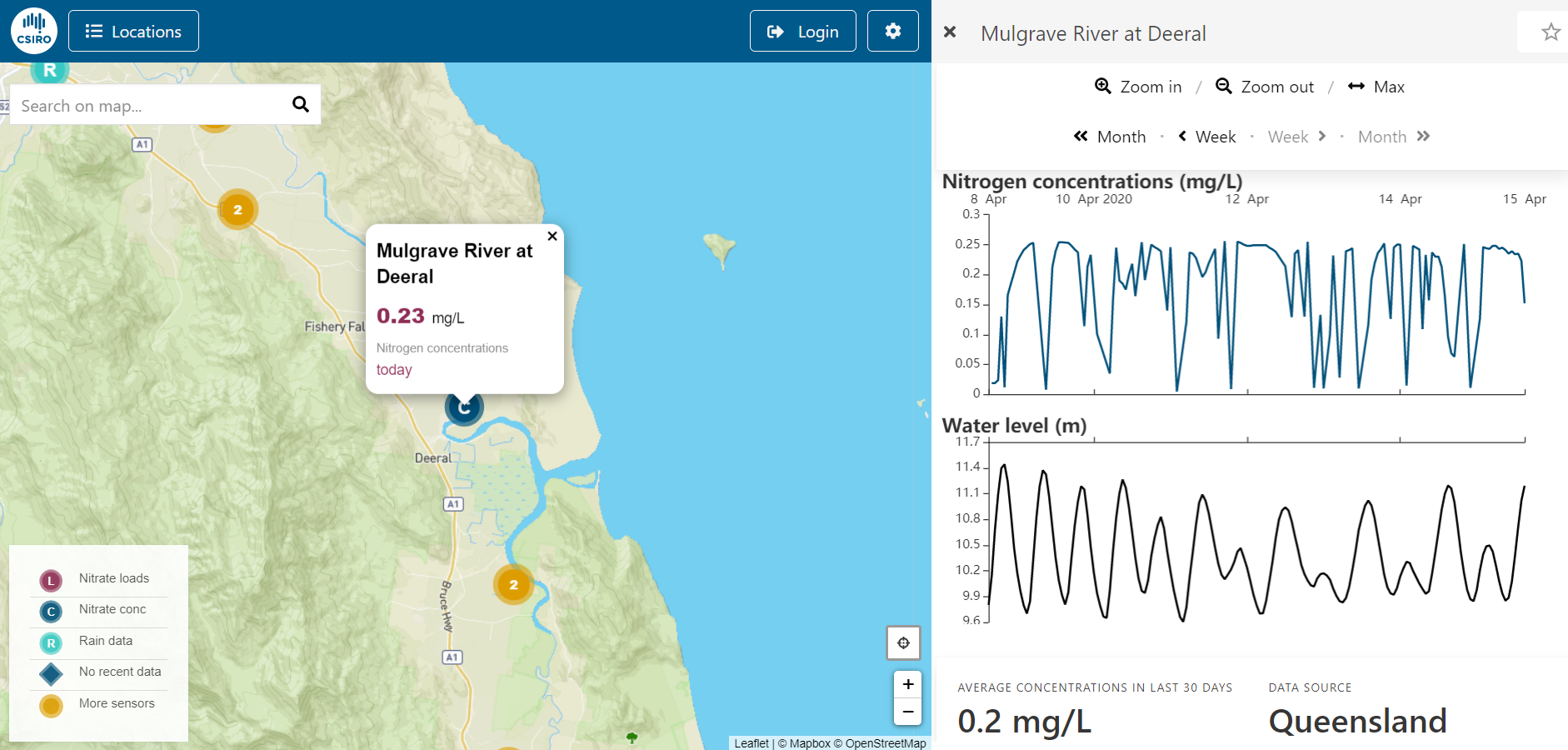

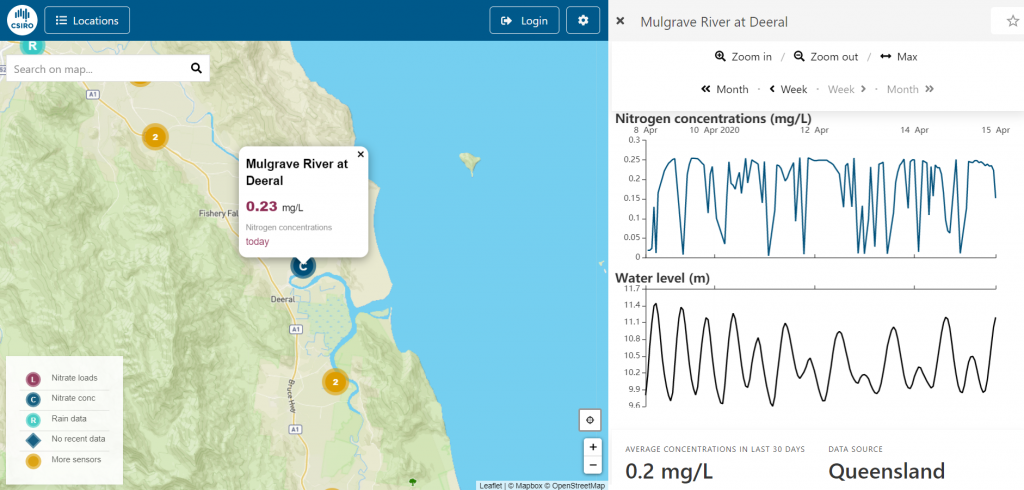

1622WQ — named in reference to the height of Queensland’s tallest mountain and the app’s goal to improve water quality — shows farmers hyper-local water quality data in the specific catchment area where they grow their crops. CSIRO launched the browser-based app in January 2020.

Relying on high-frequency, automatic sensors deployed strategically along the Queensland coast, 1622WQ provides users a detailed glimpse into the amount of nutrients that leave their land through runoff and resulting nutrient levels in local waterways connected to the ocean. While the current version of the app provides real-time nutrient estimates in only a select few locations, the specificity of the data allow farmers to differentiate between their nutrient contributions and those of their neighbors in the same catchment area, according to the CSIRO website.

“Although an app can appear simple, the smarts behind it are anything but,” Thorburn said. “The chain of information between the water quality sensors in local waterways and what you see on your phone is complex and requires substantial innovation along the way.”

The app leverages advanced machine-learning and data analysis tools used in broader CSIRO projects to which developers of typical local-scale environmental apps may not have access, described CSIRO Chief Scientist Cathy Foley.

“We’ve paired our deep domain expertise in agriculture and digital technology to provide a solution for farmers who want to remain efficient and competitive while also reducing their impact on the environment,” Foley said in the statement.

Helping Farmers Control Fertilizer

Frequent readings from the sensor network, alongside rainfall records and forecasts from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology as well as other water quality factors like creek height and turbidity, combine in 1622WQ to relate an immense volume of information in an easy-to-use field tool.

Early users of the app, such as Cairns-based sugarcane grower Stephen Calcagno, are already finding it useful.

“This will be a great tool for farmers to see the impact of their farm management and help them improve their practices and the environment,” Calcagno said in the statement. “I look forward to seeing what happens over the coming wet season.”

As the app expands to provide details on a greater number of Queensland catchments, developers are also exploring ways to make the app more valuable for its users. Potential improvements include new ways to show which parts of the sugarcane crop might require more or less fertilizer and providing more detailed information about the link between fertilizer application rates and water quality, Foley said.

“Solving complex challenges like protecting the Great Barrier Reef require deep innovation, but it’s also important that the end result is a simple and intuitive product like this app, that farmers can seamlessly integrate into their business,” Foley said.

Explore 1622WQ at the CSIRO website.

— Justin Jacques, The Stormwater Report