A look at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Atlas 14 study

When stormwater professionals design projects to prevent flooding from rainfall, they need to know how much precipitation their area can expect to receive during both common rain events and exceptionally intense storms. While modeling systems are invaluable tools to help develop stormwater infrastructure that can handle the 100-year storm and beyond, the precipitation data these systems use to recommend designs to address these storms must be accurate, up-to-date, and come from a reliable source.

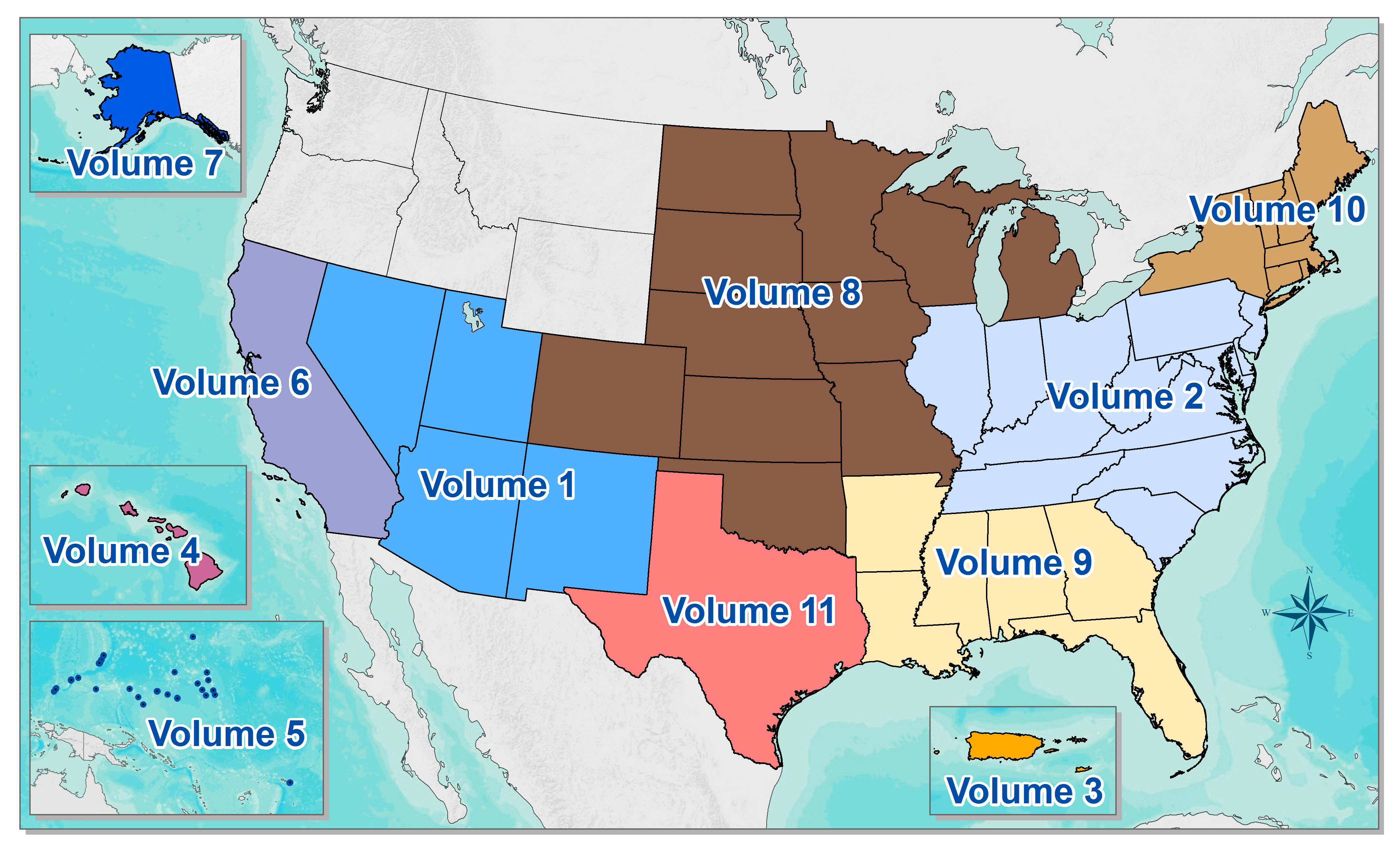

Cities and engineers around the U.S. use data from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Atlas 14 study to help design stormwater interventions according to expectations of extreme storms. First published in 2004, NOAA has released several new editions of the study on a regional basis. The agency plans to release an Atlas 14 edition for the Pacific Northwest states, the only region in the U.S. currently unserved by Atlas 14 data. Image courtesy of U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Many U.S. cities rely on data from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which offers regional estimates of rainfall depth, duration, and frequency for nearly the entire U.S. under its Atlas 14 study program. Randy Neprash, vice chair of the National Municipal Stormwater Alliance (NMSA; Alexandria, Va.) and a stormwater regulatory specialist with Stantec Consulting (Minneapolis, Minn.), underscored the importance of Atlas 14 for cities and stormwater project managers.

“Atlas 14 is absolutely pivotal and there’s nothing else like it,” Neprash said. “It’s what everybody who does this work that I’m aware of relies on in one way or another.”

But updates to Atlas 14 have far broader implications than simply guiding how engineers design stormwater infrastructure.

Rainfall’s ripple effects

Receiving an Atlas 14 update is a mixed blessing, Neprash described. On one hand, accurate precipitation data is sorely needed by the engineering community and helps support robust, resilient stormwater infrastructure. On the other hand, new data has its consequences.

For example, NOAA’s most recent Atlas 14 update covered Texas in 2018. Under the new study, the estimated rainfall for a 100-year, 24-hour storm in Houston increased by 13 cm (5 in.) per day. What was previously considered a 100-year storm for the region became a far more frequent 25-year storm, and far more Houston homes and businesses found themselves in flood zones.

“That sort of change affects property values in a really big way,” Neprash said. “A lot of homeowners in Houston may want to move away, and this new data is now indicating that there’s a good chance that selling their homes may be more difficult.”

Additionally, Atlas 14 estimates help cities develop local design standards, road elevations, construction regulations, and more. New data can help municipal stormwater managers identify specific neighborhoods where chronic flooding may become problematic before it happens. Cities may react by developing plans to address areas with high flood risks, but high costs can mean these plans often take years to fully implement, Neprash described.

Of course, the data itself does not change the reality. However, the awareness of the situation could make for difficult conversations.

“How do you tell one neighborhood that they’re in a problem area and they’re going to get fixed next year, then tell another neighborhood, ‘you live in a problem area too, but we’re not going to be able to get to you for 7 years’?” Neprash said. “It’s a political and communications challenge.”

New editions in the works

NOAA researchers began conducting regional studies of historical rainfall totals in 2004, intending to provide more localized, actionable guidance to the stormwater community than the previous standard, a nationwide rainfall frequency study released by the agency in 1961.

Atlas 14 data not only informs engineers as they design stormwater infrastructure, but also serves as a foundation for building codes, roads, construction regulations, and more, described Randy Neprash, vice chair of the National Municipal Stormwater Alliance (Alexandria, Va.) and a stormwater regulatory specialist with Stantec (Minneapolis, Minn.). Image courtesy of Erdenebayar/Pixabay

Because these regional Atlas 14 studies are most often funded on-demand by the states and agencies that use them rather than directly by taxpayers, access to Atlas 14 data is not equal throughout the country. Stormwater professionals in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, for example, are still using rainfall estimates from 1961 because NOAA has not yet published a comprehensive Atlas 14 study for the Northwest region.

Among other goals, the agency plans to release a volume of Atlas 14 for these states within the next few years, said Mark Glaudemans, director of NOAA’s National Water Center Geo-Intelligence Division.

NOAA is also in the early stages of developing two additional products (if certain conditions can be met). First, the agency is eyeing a new Atlas 14 volume that covers the entire U.S. rather than specific regions. That would be a “large undertaking” that would likely require approval and funding from the U.S. Congress, Glaudemans said. He added this project would significantly improve Atlas 14’s usefulness to a wider range of stormwater professionals. A nation-wide update of the Atlas 14 estimates would also be much more cost-efficient than the current regional funding and update approach, Neprash said. NMSA staff are advocating for a nationwide Atlas 14 update on a basis of at least every decade to keep rainfall estimates as relevant and useful as possible.

Second, the agency has discussed releasing a separate product under the Atlas 14 banner that would project how climate change might affect precipitation frequencies in the future. Current Atlas 14 projections consider the effects of climate change to an extent by documenting increasingly intense rainfall patterns over the span of decades. However, the study does not explicitly account for the rate at which climate change is accelerating, meaning that existing Atlas 14 estimates may be more conservative than actual current rainfall totals.

NOAA’s 2018 update to Texas Atlas 14 estimates “did not find statistically significant evidence of increasing rainfall due to climate change at the 1-day and 1-hour levels,” so the agency did not alter its research methods at that time, according to an April 2019 NOAA progress report.

Glaudemans noted that Atlas 14 projections that incorporate climate change are still a long way from becoming available — and may even be deemed unfeasible — as data collection and analysis methods “are still being reviewed” by NOAA researchers.