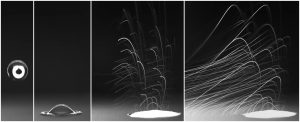

Each time a drop of rain hits the ground, small pockets of air at the surface are forced up, emitting a mist of smaller droplets in many directions as air breaks through the raindrop. Exhibiting behavior like an aerosol spray, the phenomenon could explain why freshly fallen rain leaves behind a familiar ‘earthy’ scent.

After researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge) published the first study to identify this mechanism in 2015, the team was urged by colleagues to dive deeper — if rainfall can redistribute air in different directions, can it also transport micro-organisms in the same manner?

It’s raining bugs and germs

Evidence from a follow-up article that appeared last month in the open-access journal Nature Communications points to yes.

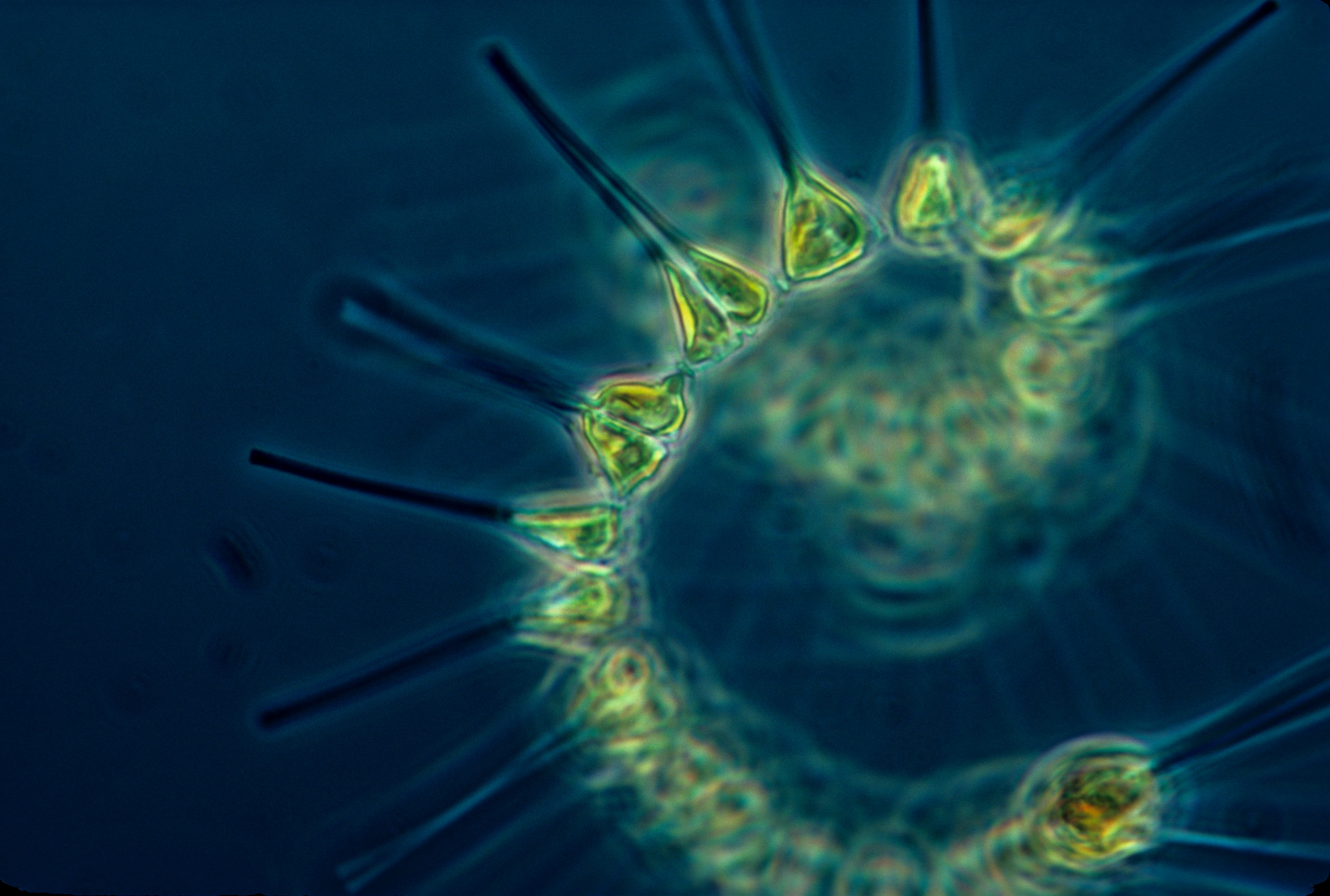

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge) used high-resolution imaging to better examine how falling rain interacts with porous surfaces. Further studies by the team found that the same mechanism that produces aerosols could also serve as an efficient means of transportation for bacteria. (Young Soo Joung, Zhifei Ge, and Cullen R. Buie)

“Imagine you had a plant infected with a pathogen in a certain area, and that pathogen spread to the local soil,” explained Cullen Buie, associate professor in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and article co-author. “We’ve now found that rain could further disperse it. Manmade droplets from sprinkler systems could also lead to this type of dispersal. So, this [research] has implications for how you might contain a pathogen.”

To arrive at their conclusion, the MIT research team studied the effect of rainfall at different speeds on six types of soils laden with a common, non-pathogenic bacterium. The researchers discharged single drops of water through a hole in the center of a small disc, placed directly above soil samples. They released drops from various heights to simulate a range of rainfall intensities. Once rain hit the soil, the discs captured aerosol sprays that the research team could then analyze for bacteria concentrations. They sought the ideal conditions under which rainfall could transmit pathogens.

The team concluded that raindrops produced the most potent aerosols when

- water droplets fell at speeds between 1.4 and 1.7 m/s (4.6 and 5.6 ft/s) —about the intensity of a light rain shower;

- surface soils were porous and mainly composed of sand and clay; and

- soil temperatures hovered around 86°F.

Lighter storms in tropical environments, then, are thought to present the highest risk of spreading bacteria.

“At this just-right speed, water wicks into the soil without splashing, but fast enough to trap air. That trapped air gets released as bubbles that burst, releasing the aerosols,” Buie said.

A surprisingly long journey

Under these ideal conditions, the aerosols were found to scatter as many as several thousand bacteria from their original soil. Much of these bacteria remained alive for more than an hour after the rain fell. Particularly in windy conditions, researchers say the possibility is likely that bacteria could be swept to a new location, where suitable conditions would enable the bacteria to resettle and propagate.

Going a step further, the MIT team calculated that global precipitation may be responsible for anywhere between 1% and 25% of the total number of bacteria originating from land-based sources.

“Further investigation is required to narrow down the range of global emission of bacteria by rain, but aerosol generation by rain could be a major mechanism of bacteria transfer into the environment,” said Young Soo Joung, lead author of the article.

Read the full article, “Bioaerosol generation by raindrops on soil,” in Nature Communications.