Washington, D.C. (above) and Philadelphia (below) are working to transform their impervious surfaces in order to better manage stormwater runoff. Public-private partnerships are helping these jurisdictions finance urban stormwater retrofits. Images from iStock.

The negative effects of stormwater — urban flooding, beach closures, nutrient pollution — create a price tag for society. To address these effects, many large cities are requiring stormwater green infrastructure be incorporated as part of construction permits or consent decrees. More than 15 states have adopted retention-based standards. Yet, traditional urban retrofit methods can be costly. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that tens of billions of dollars are spent yearly on stormwater retrofits. The U.S. also has a $600 billion (and growing) price tag for water-related infrastructure needs.

The negative effects of stormwater — urban flooding, beach closures, nutrient pollution — create a price tag for society. To address these effects, many large cities are requiring stormwater green infrastructure be incorporated as part of construction permits or consent decrees. More than 15 states have adopted retention-based standards. Yet, traditional urban retrofit methods can be costly. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that tens of billions of dollars are spent yearly on stormwater retrofits. The U.S. also has a $600 billion (and growing) price tag for water-related infrastructure needs.

Public-private partnerships (P3s) provide a way to accelerate and finance stormwater and green infrastructure investments. P3s can take many forms, including private property incentive programs and stormwater credit trading. “What is powerful about these tools is that you mobilize private capital, ingenuity, and initiative, unleashing creativity throughout the community,” said Tracy Mehan, former assistant administrator in EPA’s Office of Water and now adjunct professor at George Mason University.“P3s can offer a more flexible and efficient means of achieving regulatory outcomes.”

Mehan moderated an Aug. 27 Water Environment Federation (WEF) webcast on innovative approaches to financing stormwater investments. “The world is awash in private capital,” he said. P3s enable communities to leverage a dedicated funding stream to bring in “many multiples” more than a stormwater fee. Just as importantly, P3s can help finance the ongoing maintenance of green infrastructure projects.

“At best, federal dollars available for addressing water quality can help with 10% to 15% of the problem, so the rest of the money, where does it come from?” asked Deputy Director Dominique Lueckenhoff of the EPA Region 3 Water Protection Division. Lueckenhoff leads the region’s community-based P3 initiative and also spoke during the WEF webcast.

Investment banks and financiers see innovative stormwater management as an emerging market. Such stable regulatory drivers as consent decrees and stormwater permits are attractive to private investors because they create surety for funding, Lueckenhoff said.

With so much potential behind the concept of P3s, why are they not more common in the stormwater sector? Hurdles identified by EPA include the perceived loss of public control. However, a P3 should start “with a partnership in mind,” Lueckenhoff said. From there, participants should decide jointly how to achieve the community’s goals and “then create the finance structure to make that happen.” Another common assumption is that private financing is more expensive. Particularly with long-term models, however, EPA is seeing cases where private financing is less expensive. According to EPA, P3s can reduce costs to government 20% to 50% or more. Additional P3 benefits include decreasing or eliminating the need for bonds, shared risk between public and private partners, and increased accountability.

Philadelphia’s Incentive Programs

A green roof retrofit on the PECO Building in Philadelphia helps to fulfill the city’s Green City, Clean Waters initiative. Image by the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD)

Presented during the Aug. 27 webcast, Philadelphia’s Stormwater Management Incentives Program (SMIP) and Greened Acre Retrofit Program (GARP) are examples of P3s. The programs support the city’s Green City, Clean Waters initiative, which launched in 2011. An objective of the initiative is to control runoff from 4050 ha (10,000 ac) and to reduce overflows by 85% over 25 years. “We are looking to transform the city, to transform a swath of impervious area,” said Erin Williams, stormwater incentives manager with the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD). The program “turns rainwater into a commodity to be saved, traded, and used to stimulate our green economy.”

By 2025, the city hopes to achieve nearly 10,000 greened acres. A greened acre is calculated by multiplying impervious cover and water depth. This equates to managing about 34% of the city’s impervious cover.

While government generally starts by incentivizing a behavior and later regulates it, Philadelphia has done things differently. They launched stormwater regulations in 2006 followed by a parcel-based stormwater fee in 2010, and then in 2012, the city started the first of its incentivized grant programs.

Since promulgating the 2006 regulations, nearly 500 development projects have been approved with more than 5.7 million m3 (1.5 billion gal) of rainfall managed annually. “These are greened acres that we can count without cost to the government,” Williams said.

SMIP and GARP are grant programs for non-residential PWD customers that further encourage private participation in design and construction of stormwater retrofit projects. They are paid for by the city’s parcel-based stormwater fee, which is revenue neutral with funds recycled back into PWD’s programs.

The Greene Street Friends School is an example of a Stormwater Management Incentives Program retrofit. Half of the school parking lot was turned into a rain garden, managing stormwater and making the property more attractive. Image by PWD.

Since the start of SMIP in 2012, PWD has received 120 applications. The 36 projects approved to date have cost the department $15.2 million, resulting in 205 greened acres at a cost of $75,000 per greened acre. “This program is getting really cost effective greened acres. It’s been such a win-win for Philadelphia and our ratepayers,” Williams said.

Projects must manage at least the first inch of stormwater runoff onsite. This condition is consistent with the city’s consent decree. “Everything we do, we try to tie back to Green City, Clean Waters, to our permit compliance goals,” Williams said.

Both SMIP and GARP include a focus on maintenance, requiring a 45-year maintenance and operations agreement. This ongoing care is critical to protecting the city’s investment.

GARP, announced July 1, evolved from SMIP. It targets larger-scale stormwater retrofits in Philadelphia’s combined sewer service area. Projects must be at least 4 ha (10 ac) and can span multiple properties that are not necessarily adjacent. The goal of GARP is to attract a wider audience and facilitate cheaper projects by honing in on economy-of-scale benefits.

“With GARP, we are now able to sell stormwater management not just to property owners but to the private sector — to engineers, nonprofits, and stormwater solution companies that want to retrofit private property for stormwater management and want to do it in the most cost effective way possible.”

While SMIP involves an agreement between the property owner and PWD-partner Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC), GARP is an agreement between a third party and PIDC. GARP applicants are project aggregators and could be a company that designs, builds, and maintains stormwater management facilities. The applicant also could be a business improvement district or a nonprofit applying on behalf of multiple property owners. “There are many ways GARP can come about, and we are keeping it open-ended for now,” Williams said.

SMIP and GARP are offered in tandem all year long, and PWD issues decisions quarterly. While SMIP grant requests are limited to $100,000 per impervious acre managed or less, the limit for GARP is slightly lower at $90,000. GARP projects, however, are expected to be less expensive. Upon successful construction, grantees also can receive credits toward their stormwater fees.

Washington, D.C. Stormwater Retention Credit Trading

Stormwater retention green infrastructure gradually makes the District “spongier.” Image by the District Department of the Environment

Historically, the District Department of the Environment (DDOE) has faced difficulty getting green infrastructure installed on private property. However, its Stormwater Retention Credit (SRC) trading program is helping to tap into the private side.

“With the stormwater management regulations we have put in place, we are really trying to internalize the externalities of stormwater runoff into the costs of development,” said Branch Chief Brian Van Wye of the DDOE who spoke on the Aug. 27 webcast. “Historically, development has resulted in significant runoff in the District, but with our current regulations, new development is driving green infrastructure retrofits of previously developed areas.”

A single 31-mm (1.2-in) storm falling on the District produces about 2 million m3 (525 million gal) of stormwater runoff. The basic solution is to retrofit the impervious surfaces to mimic natural land cover — “to make the District spongier,” Van Wye said.

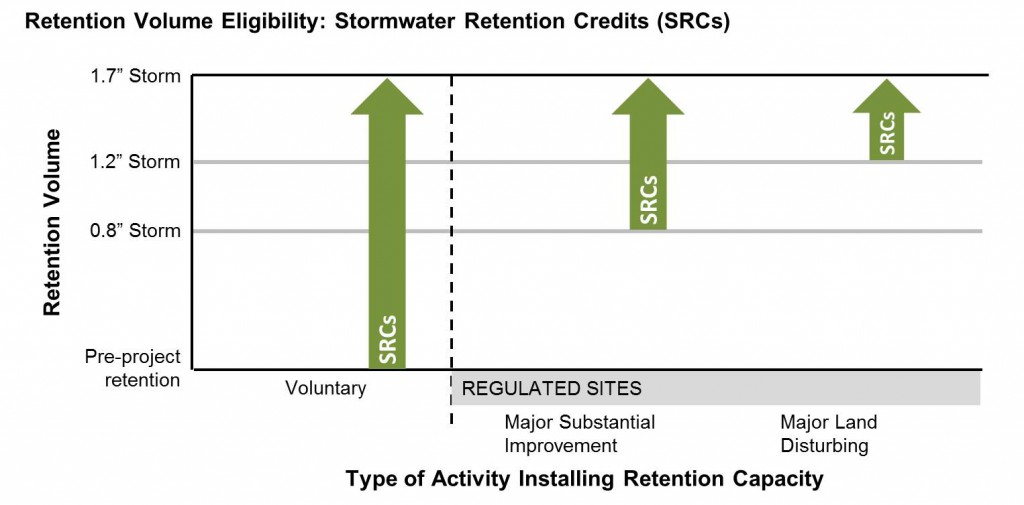

There are two triggers for the District’s stormwater management regulations, promulgated in July 2013. A major land disturbing activity of 465 m2 (5000 ft2) must retain the volume of a 31-mm (1.2-in) storm. Major Substantial Improvement projects have the same size threshold, applied to building footprint and area of land disturbance, but these projects are only regulated when construction costs are 50% or more of the pre-project value of the structure. Improvement projects have a lower runoff retention requirement of 20.3 mm (0.8 in).

“Gradually over time, we expect regulated development to retrofit most of the District’s impervious area” Van Wye said. “But it’s going to take a long time since 43% of District land is impervious, and only 1% of that land development triggers the regulations in an average year.”

Most regulated development in the District is redevelopment — about 200 projects per year — and the total area subject to stormwater regulations annually is about 1.4 million m2 (15 million ft2), or approximately 1% of land area. Yet the District still touches ten times more area through regulation than through DDOE cost-share and incentive programs, including direct investments on District property.

To accelerate green infrastructure retrofit installation, DDOE can purchase and retire SRCs, but as these SRC-generating areas undergo regulated development, District ratepayers and taxpayers will not have to bear ongoing retrofit costs. “Using this approach would allow us to taper our investment over time as more and more land in the district is regulated,” Van Wye said.

As DDOE buys and retires credits, it also fuels SRC market demand and reduces costs to DDOE and its ratepayers compared to paying for retrofits up front.

In addition to being a tool for DDOE to meet water protection goals and requirements, the trading program also provides more flexibility for regulated developments. Regulated projects must retain onsite at least 50% of the volume associated with their applicable retention standard. But recognizing that it would be relatively difficult or costly for some regulated projects to achieve the onsite retention standards, the remaining percentage can be achieved offsite, by purchasing SRCs, paying an in-lieu fee, or a combination of both.

The cost of the in-lieu fee is about $1 per liter ($3.5 per gal) per year, which is based on DDOE’s capital costs for installing and maintaining green infrastructure in the District. The idea is that DDOE would then install the practices itself. The price of the traded SRCs, in contrast, is a negotiation. “We don’t think the in-lieu fee will be the most attractive option, but that privately traded stormwater retention credits will be more attractive,” Van Wye said.

SRCs can be generated and certified through DDOE for 3-year cycles either by exceeding regulatory requirements or by voluntarily installing retention practices. Those that generate SRCs can also receive stormwater fee reductions. This presents a “good opportunity for property owners to voluntarily retrofit and get a financial benefit,” Van Wye said.

SRCs can be generated by exceeding regulatory requirements or by voluntarily installing retention practices. Eligible credits are capped at the 1.7-in storm. Figure by DDOE

…

The program presents an ongoing opportunity and incentive for construction managers and property owners to look for cost effective green infrastructure opportunities. According to Van Wye, there are about 1300 projects that trigger erosion and sediment control requirements in the District each year. While not required to manage stormwater, they do have engineering and construction resources mobilized. “We want to create an incentive for these projects and property owners to think about where they can install green infrastructure at a relatively low marginal cost and generate credits,” said Van Wye. “We are looking to transform the mindset of property owners and construction managers.”

Other opportunities include the 30,000 building permits issued annually, and the 125,000 stormwater rate payers.

In addition to the economic benefits, the trading program also provides as good or better benefits to District waterbodies. “There is a strong potential to capture more stormwater on an annual basis through trading than by requiring the total volume to be managed onsite,” Van Wye said.

Additionally, DDOE expects that more first flush volume, which contains the greatest pollutant load, will be captured because of the trading program. DDOE also predicts that it will better protect small tributaries, which are more sensitive to the effects of stormwater, by relocating green infrastructure outside of the urban core to areas where building is less expensive. Shifting the placement of green infrastructure should also benefit less affluent communities, and the overall increase in retention-based green infrastructure should boost green jobs.