During the last few decades, the concept of green infrastructure (GI) has risen to prominence in the stormwater management sector. Driving the trend are countless researchers, practitioners, and advocates who demonstrate GI’s potential to meet multiple community goals at typically lower costs than traditional approaches to flood control.

However, institutionalizing GI as a standard component in stormwater management plans at all levels and jurisdictions requires a steady stream of champions equipped with the necessary knowledge, perspectives, and communication skills to influence decision-makers.

In July, the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA; Ashburn, Virginia) and the Willamette Partnership (Portland, Oregon) released a suite of resources aimed at familiarizing park professionals with GI and approaches to help nurture its adoption. Because the goals of GI and parks often align — such as by improving access to nature for urbanites, promoting public health, and enhancing climate change resilience — park professionals are natural champions for GI, described NRPA Vice President of Programs and Partnerships Kellie May in a release.

“These resources have been developed to promote parks as optimal spaces for green infrastructure and provide park and recreation professionals a roadmap to securing necessary support and investments,” May said.

Better Communication, Policy, and Advocacy

Greener Parks for Health guides cover strategies for communicating GI benefits to different audiences and identify specific actions government entities can take to remove barriers to GI adoption. Recommendations outlined in the resources are backed by hundreds of cited, peer-reviewed studies that detail how implementing GI in public parks can improve social, physical, environmental, and economic health.

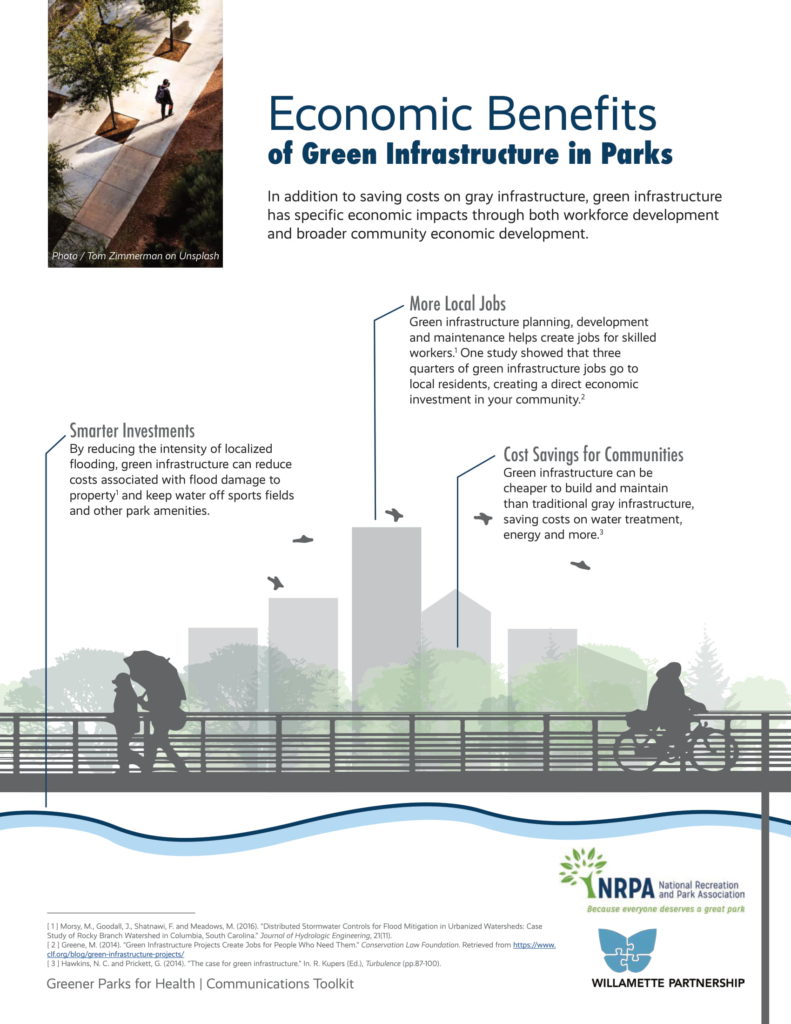

The first piece is a 32-page communications toolkit featuring a series of one-page factsheets designed to convey the benefits of GI in public parks quickly and clearly. Each of the factsheets, which are intended for use on social media, at community gatherings, and during meetings with elected officials, focus on a different type of benefit that GI can help provide. For example, one document covering GI’s economic benefits emphasizes GI construction and maintenance creates new jobs for skilled workers, citing a study finding that about 75% of GI jobs typically go to local residents. It goes on to describe that GI is often cheaper to build and maintain than conventional flood-prevention measures and can help mitigate weather-related disruptions to other park amenities.

Second, a policy action framework draws on a collection of case studies to highlight existing local, state, and federal policies that encourage GI adoption and improve its accessibility. The framework also suggests additional ways to remove barriers to GI, including new funding instruments and more flexible regulatory permits. For example, the guide suggests that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could inspire GI adoption by incentivizing nature-based elements in Clean Water Act permits and expanding Clean Water State Revolving Fund programs to provide exclusive investment for GI and other stormwater projects. Additionally, the framework encourages new, GI-based workforce training initiatives, such as the National Green Infrastructure Certification Program.

The final piece, an advocacy toolkit, touches on strategies that stormwater management and park professionals can use to be more effective leaders in gaining support for GI. It provides in-depth detail on tailoring GI messaging based on one’s target audience and their motivations. The toolkit also identifies realistic goals to help encourage GI, such as forming public-private partnerships to help fund GI in public parks or supporting local efforts to facilitate GI such as implementing stormwater utility fees.

Green Infrastructure Promotes Equity

Similar to public parks, GI calls for decentralization at the conceptual level. Just as GI becomes a viable approach to stormwater management across a large area only when widely distributed, park professionals aim to site green spaces in ways that offer equitable access to nature for the largest number of people. In practice, however, parks are often concentrated closer to high-income and high-education neighborhoods, resource authors describe. Because of GI’s versatility and ability to benefit public health, a key focus of all Greener Parks for Health materials is using GI to improve access to nature in under-resourced and historically disenfranchised communities.

“Getting people equitable access to nature is one of the best public health moves we can make as a society,” said Barton Robison, lead for the Willamette Partnership’s Oregon Health & Outdoors Initiative, in a release.

As several studies cited in the communications toolkit describe, implementing GI in urban areas correlates positively with decreased narcotics possession, lower crime levels, more numerous volunteering opportunities, better memory and mental health, and reduced rates of obesity. It can provide these benefits in addition to mitigating flooding and urban heat-island effects, providing additional habitat for wildlife, and enhancing climate-change resilience, authors describe.

“Even if it’s just a safe place for families to picnic or buddies to play pickup basketball, the physical and mental health benefits of green space are undeniable,” Robison said. “…planners, park managers, city engineers, and community activists should take a serious look at how GI and parks provide opportunities to keep people healthy while actively creating health equity across communities.”