In southern Italy, the pristinely preserved remains of the ancient Roman city of Pompeii have mystified historians and archaeologists since they were rediscovered nearly 300 years ago. Ongoing expeditions continue to reveal new details about the city and its people, believed to have been decimated by the sudden eruption of nearby Mount Vesuvius around 79 CE.

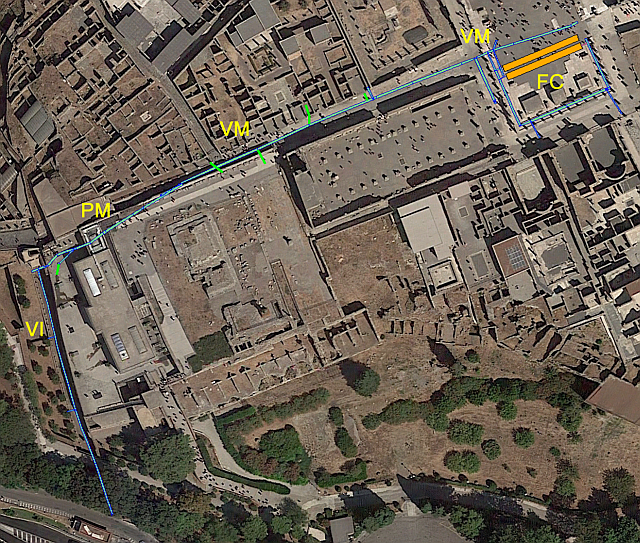

Researchers with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii have explored and mapped 457 m (1,500 ft) of ancient stormwater tunnels beneath the ancient Roman city of Pompeii. Because the region still experiences frequent flooding today, the park plans to bring the tunnels back into functioning condition, said director Massimo Osanna. Photo courtesy of Archaeological Park of Pompeii

Archaeological Park of Pompeii (APP) researchers have spent two years uncovering new details about how ancient Pompeian engineers approached stormwater management. They surveyed 457 m (1500 ft) of stormwater tunnels that once carried runoff from the city’s center toward the Bay of Naples. APP is now working to restore functionality to the ancient tunnels while respecting and preserving their historical value, said park director Massimo Osanna. Bound by the Volturno River and the Apennine Mountains, heavy rainstorms presented – and continue to present — severe flooding risks to low-lying Pompeii.

“Since we have problems today with flooding from rain, we will start using [the tunnels] again,” Osanna told The (London) Times in February. “The fact we can do this is testament to the excellent engineering skills at the time.”

How Romans dealt with runoff

Archaeological researchers had known about the existence of an expansive tunnel system underneath Pompeii for decades, describes an APP release about the discovery. However, previous expeditions underground had different goals, and uncovered only the most basic information about how the tunnels functioned, when they were built, or how far they stretched.

Because of the logistical difficulty of navigating these underground structures without disturbing their archaeological provenance, APP enlisted professional cave analysts from the Cocceius Association to comprehensively map and study the narrow tunnel system.

Evidence suggests that Pompeii’s ancient stormwater tunnels collected runoff from the heavily trafficked Civil Forum, conveyed it underground beneath the Via Marina, and eventually discharged it into the Bay of Naples. Photo courtesy of Archaeological Park of Pompeii

At the former site of the Civil Forum, a main gathering place and one of the most heavily trafficked areas in the city, a system of surface-level storm drains directed rainwater into two large, stone cisterns underground. Runoff collected in the cisterns would feed into rudimentary tunnels, also carved through stone, that ran beneath the busy Via Marina thoroughfare and into the Bay of Naples.

Evidence of the survey suggests the tunnel system evolved over three distinct historical periods, which could mean the channels served Pompeii residents for approximately 300 years. Researchers believe the oldest parts of the system date back to the late 3rd-century BC, around the death of Alexander the Great and before the rise of the Roman Empire. Extensions to the tunnels are thought to have been made during the 1st-century BC, around the reign of Augustus Caesar, first emperor of Rome. APP describes that some parts of the system appear slightly newer, likely within the decades leading up to the city’s eventual destruction.

After the entire system is cleared of debris and the drains — until recently blocked by soil, ash, and other obstacles — are reopened, the tunnels will soon convey stormwater runoff for the first time in nearly 2,000 years, according to APP.

“This initial, but complete, exploration of the complex system of underground canals confirms the cognitive potential which the Pompeian subsoil preserves and demonstrates how much still remains to be investigated and studied,” Osanna said.

Ingenuity from antiquity

The stormwater system beneath Pompeii was sophisticated, but not unique among ancient civilizations faced with the timeless challenge of flood mitigation.

On the eastern coast of present-day China, for example, inhabitants of the ancient city of Liangzhu faced frequent flooding from the nearby Yangtze River during monsoon season. As many as 5,100 years ago, ancient engineers built one of the world’s oldest-known water management systems consisting of several dams, levees, and canals. Historians believe the project involved thousands of workers and took more than a decade to complete, and evidence suggests the system also provided extra irrigation water for rice production. Read more about the Liangzhu flood management system on WEF Highlights.

Examples of sophisticated ancient water management systems can be found around the world, including in China, the Middle East, and North America. Photo courtesy of Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology

In the deserts of present-day Iran, which receive less than 127 mm (5 in.) of rainfall per year, the ancient Persians relied on sophisticated tunnels to harvest as much water as possible to support their growth. Persian qanats were unique types of hand-dug tunnels, established more than 3,000 years ago, which transported water from elevated sources directly into farming fields. Some qanat systems lay as many as 61 m (200 ft) underground, and they were meticulously designed and managed to ensure adequate water quality and equity of access. Read more about Persian qanats on WEF Highlights.

Around 600 CE, the Hohokam Native Americans built a sophisticated irrigation network that archaeologists estimate may have provided water for up to 44,516 ha (110,000 ac) of growing grounds in present-day central Arizona. Originating from large, hand-dug canals measuring up to 4.6-m (15-ft) deep and 13.7-m (45-ft) wide, the Hohokam conveyed water from the Salt River throughout its territory with hundreds of miles of branching irrigation ditches, supporting the largest population in the prehistoric Southwest, according to the Arizona Museum of Natural History. Although the Hohokam civilization disappeared around 1450 CE, their irrigation tunnels were sophisticated enough to be revived by Gold Rush-era prospectors around 400 years later. Read more about the Hohokam tunnel complex on WEF Highlights.

— Justin Jacques, The Stormwater Report