In the U.S., the “rain follows the plow” myth originated in the mid-1800s to help recruit homesteaders to the Great Plains region. The theory, which has never been fully disproven, states that preparing soil for agriculture in dry regions enables rain to seep deeper into the ground, which eventually results in a more humid climate and additional rainfall. Free-Photos/Pixabay.

A theory in debate since the mid-1800s holds that disturbing the soil in dry regions through agriculture allows rain to seep into the ground, raising moisture in the area and eventually coaxing more rain to fall. In other words, according to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Center for Great Plains Studies, “rain follows the plow.” Support for the theory plummeted in the 1890s when severe droughts affected the U.S. Great Plains region, where the notion was used to help justify westward expansion into what was then known as “The Great American Desert”.

But in the modern age, climatologists are finding evidence that human land use actually may affect precipitation, at least at a local level. For example, the presence of large cities or widespread corn farming may make rainfall more likely, according to recent studies. A new paper from the University of Arizona (Tucson) claims that increased soil moisture may lead to rain, but only under specific atmospheric and climatic conditions.

“In addition to, and partly motivated by, the ‘rain follows the plow’ myth, many scientific papers have been published with conflicting results,” said Xubin Zeng, a study co-author. “Our goal was to resolve this controversy.”

Morning moisture affects afternoon showers

Focusing on about 23,300 km2 (9000 mi2) in Kansas and Oklahoma, Zeng and doctoral student Josh Welty began their research by pulling historic open-source data on soil moisture and precipitation from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Southern Great Plains atmospheric observatory. To best represent the growing season, they studied conditions between June and September for 9 consecutive years beginning in 2002, measuring soil moisture at a shallow depth of 5 cm (1.9 in.) beneath the surface.

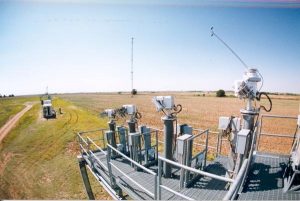

Researchers from the University of Arizona (Tucson) used soil moisture and rainfall data from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Southern Great Plains research site to examine the relationship between the two variables. DOE operates sensors and other research equipment in an area measuring 23,300 km2 (9000 mi2) in Kansas and Oklahoma, providing open-source climate and atmosphere data to the public. U.S. Department of Energy.

The team analyzed patterns between morning soil moisture, recorded by DOE sensors between 7 and 11 a.m., and the occurrence and intensity of rainfall in the afternoon. Their findings suggest “rain follows the plow” proponents may have failed to consider two ingredients to make rain:

- upward motion of air from the surface into cool parts of the atmosphere and

- water vapor.

According to the study, heat on a warm day turns soil moisture into water vapor throughout the morning. With enough water vapor in the air, the likelihood of rain then comes down to the moisture of afternoon winds, which also supply upward motion. When winds carry only a small amount of moisture into the region, dryer soils were found to be better than wet soils at attracting rain.

“The dry soils that enhance afternoon rain are acting like conveyor belts for warm air that’s being sent into the upper atmosphere,” Zeng said. “Combine that upward motion with moisture and a water vapor source, and the result is afternoon rain.”

A model for climatologists

The researchers discovered an additional relationship between moist soil and increased rainfall when afternoon winds are wetter, but they note that “this correlation is markedly reduced in magnitude and becomes insignificant when all regime days are considered.”

“Soil moisture effects on afternoon rain … may be more thoroughly understood by accounting for how much water vapor the wind brings on a daily basis,” Welty said.

Rain, then, could follow the plow, according to the study – so long as soil moisture and wind moisture are in the correct balance. The researchers say the conclusion, tailored to the Southern Great Plains, could be a useful starting point to better understand how land use affects precipitation anywhere on the planet using similar data.

Read “Does soil moisture affect warm season precipitation over the Southern Great Plains?” in Geophysical Research Letters.