Conventional methods used to inventory macroinvertebrates are extremely time-consuming. (Photo: Eawag, Elvira Mächler)

Effective environmental management depends on a detailed knowledge of the distribution of species. But taxonomists are in short supply, and some species can be difficult to identify, even for experts. The Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), in collaboration with the Canton Zurich Office of Waste, Water, Energy and Air, is now pursuing a new approach for species identification, requiring no more than samples of environmental DNA (eDNA).

Because organisms continuously release genetic material into the environment in the form of feces, hair, or skin cells, water samples collected from a river or lake contain innumerable fragments of DNA. As long as the relevant genetic code is known, these DNA segments can be assigned to particular species, using the latest molecular biological techniques and global databases.

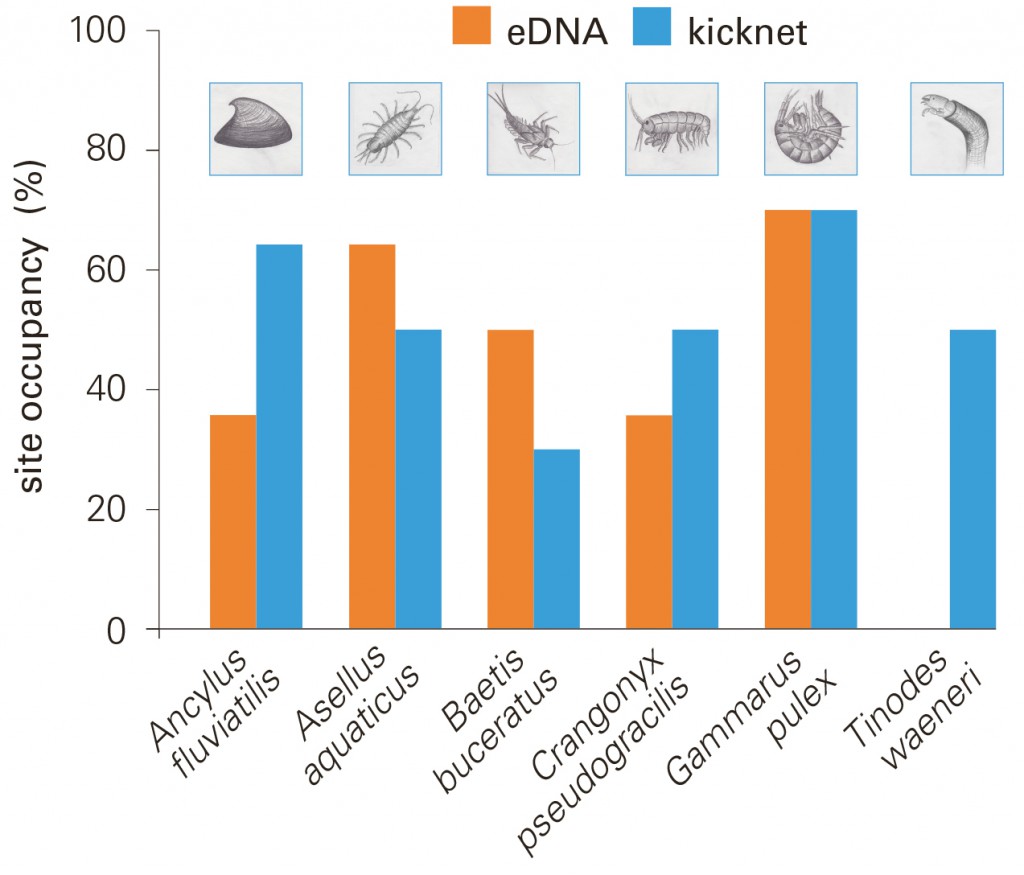

In a study published in the December 2014 issue of Freshwater Science, researchers investigated whether this method is suitable for the detection of macroinvertebrates. Organisms such as mayflies, amphipods, mussels, or snails are important bioindicators used in the assessment of water quality and ecotoxicity. Water samples were collected from 14 lake and river habitats in Canton Zurich for eDNA analysis. Researchers also collected macroinvertebrate species in the conventional manner, by kicknet sampling.

The eDNA method effectively detects a wide range of macroinvertebrate species; in some cases, the results are better than with the conventional approach.

While the two methods did not always deliver the same results, five of the six target species were reliably detected by both methods. The eDNA method appears to be more sensitive, especially for organisms occurring in small populations. With this approach, the rare mayfly Baetis buceratus was additionally detected at two sites where no Baetis specimens were found by kicknet sampling. According to project leader Florian Altermatt, the new method also may be suitable for the detection of invasive species at an early stage of colonization. In the U.S. and France, it is already being tested for invasive carp species.

The eDNA method offers additional advantages. Since eDNA is ubiquitous in freshwater throughout the year, the findings reflect the situation of an entire catchment. Surveillance also is less time-critical. In contrast, kicknet sampling provides only a snapshot, and for many species it can only be carried out at certain stages of the life cycle and certain times of the year. For eDNA analysis, organisms do not have to be removed from a river or lake and – in principle – hundreds of species can be detected at the same time. This means that continuous monitoring of freshwater biodiversity could one day become possible, just as chemical parameters are routinely monitored today.

This, however, is still a long way off. Apart from the need for further refinements, the method is still costly and time-consuming. But Altermatt believes it will not take long for technical standards to be established, permitting efficient operation. However, the new method will not wholly replace the conventional approach. Altermatt argues that the benefits of both approaches should be exploited. In addition, taxonomists will remain indispensable for validation and calibration of the new procedures. Read more.